By George Vardas

Vice-President, The Australian Parthenon Committee

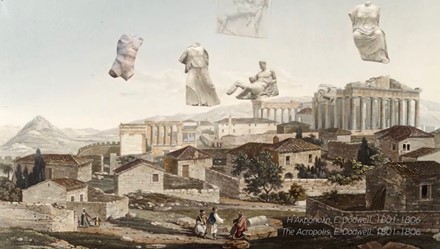

On 29 September 2021, UNESCO through its independent cultural heritage advisory body issued a decision or declaration highly critical of the UK Government’s ongoing failure to deal with the vexed issue of the return of the Parthenon Sculptures, cultural artefacts that were plundered by Lord Elgin at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

To understand why the UNESCO Committee finally came to this position it is necessary to consider the history of the seemingly futile attempts to bring the British and Greek sides together in an international forum to seek to resolve what is arguably the world’s oldest and most well-known cultural property dispute.

READ MORE: UNESCO puts pressure on UK to hold talks with Greece over Parthenon Marbles.

In 1976, at the request of UNESCO, a committee of experts met in Venice to study the question of the restitution or return of lost cultural property, whether as a result of foreign or colonial occupation or following illicit traffic before the entry into force, for the States concerned, of the UNESCO 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. It was recommended that UNESCO proceed with the creation of an international body responsible for finding ways to assist with and facilitate bilateral negotiations between the countries concerned for the return or restitution of cultural property.

The UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Countries of Origin or its Restitution in case of Illicit Appropriation (ICPRCP) was established at the 20th session of the Conference General of UNESCO in 1978 as a permanent intergovernmental body. Pursuant to Article 4 of its Statutes, the Committee is responsible, inter alia, for seeking ways and means of facilitating bilateral negotiations for restitution or return; promoting multilateral and bilateral cooperation with a view to the restitution or return of cultural property to its countries of origin and promoting exchanges of cultural property.

Cultural property has been defined as a people’s “irreplaceable heritage, the most representative works of a culture”. It was in that context that M. Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow, the then Director-General of UNESCO, issued this plea on 7 June 1978:

“The return of a work of art or record to the country which created it enables a people to recover part of its memory and identity and proves that the long dialogue between civilizations which shapes the history of the world is still continuing in an atmosphere of mutual respect between nations.”

The Greek Case and the British stonewall defence:

At the UNESCO World Conference on Cultural Policies held in Mexico in August 1982 Melina Mercouri, the Greek Minister for Culture, famously moved a resolution for the return of the sculptures. Her British counterpart replied that the UK Government “could not interfere in the affairs of a private establishment like the British Museum”. A harbinger of the strategy deployed by the British side for the next four decades.

READ MORE: On This Day: Melina Mercouri calls for the Parthenon Marbles to be returned to Greece.

Since 1984, ICPRCP has made countless ‘recommendations’ for the resolution of the dispute between Greece and the United Kingdom over the Parthenon Sculptures – which the British side has continued to ignore. As early as the fourth session the ICPRCP noted that it was important for it to make sure that the negotiations over the so-called ‘Elgin Marbles’ did not reach a deadlock but continued with a view to achieving a solution acceptable to both parties.

At the ninth session of the Committee held in Paris in September 1996, a by now all too familiar recommendation was adopted for the Director-General of UNESCO “to continue his good offices to resolve this issue and to undertake, as a matter of priority, further discussions with both states”.

However, the British side continued to argue that the British Museum was independent of the Government and that its enabling statute limited the circumstances in which it may dispose of any object in its collection, going so far as to suggest that even if the British Museum Act was amended but the British Museum Trustees were not prepared to return the marbles, any attempt at compulsion by passing further laws could be construed as being confiscatory and contrary to Article 1 of the First Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights . It was subsequently leaked to The Economist that this argument had simply been raised as a “delaying tactic”.

READ MORE: ‘A classy act’: Philhellene, Stephen Fry, on returning the Parthenon Marbles to Greece.

Before a 2000 House of Common Select Committee inquiring into the illicit trade in cultural property, the British Museum emphasised that it holds “in trust for the nation and the world a collection of art and antiquities” and that it constitutes a “reference library of world cultures”, providing an “international context where cultures can be experienced by all, studied in depth and compared and contrasted across time and place”.

For good measure they also claimed the sculptures are now an integral part of English heritage:

“The Sculptures from the Parthenon now in the British Museum have … been in London longer than the modern state of Greece has been in existence. As a result, they have become part of this country’s heritage and have acted as a focus for western European culture and civilisation. They have found a home in a museum that grew out of the eighteenth century ‘Enlightenment’, whereby culture is seen to transcend national boundaries.”

The eleventh session of the Committee was held in Cambodia in March 2001. The Committee noted that the issue of the Parthenon Marbles was still pending. According to Lyndel Prott, a well-renown Australian cultural law expert and then director of UNESCO’s Cultural Heritage Division, the issue of the Parthenon Sculptures was very important and UNESCO had been “trying to avoid any confrontation” during the meetings of the Intergovernmental Committee.

Well up until now they had succeeded in avoiding conflict.

In 2003, the new director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, repeated the mantra of the museum when he criticised Greece’s position of “perpetual possession of all the Parthenon sculptures” and provided the following rationale:

“(H)alf the marbles are lost forever. We’re talking about the proportions of what remains. They can’t get them up onto the Parthenon because it’s a ruin, so the argument that one normally makes for gathering things together from the same ensemble, that you are restoring or recovering the work of art, doesn’t apply here. One’s got to recognise that their life as part of the Parthenon is over. It seems to me rather a fortunate accident of history that about half of what survived is in London.”

This condescending attitude was to be echoed by his successor, Dr Hartwig Fisher, some 16 years later when Fischer infamously described Lord Elgin’s plunder and removal of half of the sculptures from the Parthenon as a “creative act”.

ICPRCP again met in Paris in September 2010 at the 17th Session and issued yet another “recommendation” in which it again invited the Director General to assist in convening the necessary meetings between Greece and the United Kingdom, with the aim of reaching a mutually acceptable solution to the issue of the Parthenon Sculptures.

But the true nature of the British response was laid bare in the UK House of Commons on 22 June 2011 when the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, was asked by Andrew George, a Liberal Democrat MP and leading British campaigner for the sculptures, whether Britain was prepared to put right a 200-year wrong by giving back the marbles. Cameron was interrupted as he was about to say that he did not agree with that view .

The ‘witty’ exchange between the Speaker of the House and Cameron was recorded on Hansard:

The Speaker: “Order. I want to hear the Prime Minister’s views on marbles.”

The Prime Minister: “The short answer is that we are not going to lose them.”

The British Government has never shown any respect for the Greek claim and has continued to resist attempts to have a meaningful and genuine dialogue between the countries. Even Greece’s attempt in 2013 to invoke the mediation and conciliation procedures available through UNESCO were belatedly rejected by both the British Museum and the UK Ministry of Culture.

The meetings held of the ICPRPC in 2014, 2016 and 2018 all concluded with the same predictable recommendation urging the parties to continue talking.

At the 22nd Session of ICPRCP: UNESCO bares it teeth

The 22nd Session of the UNESCO Committee took place on 27-29 September 2021 in Paris (with many delegates attending virtually) after the original conference scheduled in May 2020 was postponed due to the pandemic.

It was to break the mold of previous ICPRCP meetings.

The Egyptian diplomat, Maged Mosleh, was voted as Chairperson of the Committee with Vice-Chairs taken by Greece, Japan, Mexico and Moldova.

Apart from procedural matters the Committee’s agenda focussed on two items, the Parthenon Sculptures (Greece) and the case of the Broken Hill Man Skull (Zambia). There was also consideration of a case of an illicitly acquired Benin bronze owned by a Belgian art dealer but detained by British authorities pending resolution of the dispute between Nigeria and Belgium.

At the beginning of the first day the Committee stated its desire that member states conduct bilateral negotiations on the return and restitution of cultural property and in relation to the case of the Parthenon Sculptures specifically evoked the recommendation from the last session and expressed its continuing concerns and invited both Greece and the United Kingdom to find an “equally acceptable solution”.

READ MORE: Boris Johnson rules out return of Parthenon marbles to Greece.

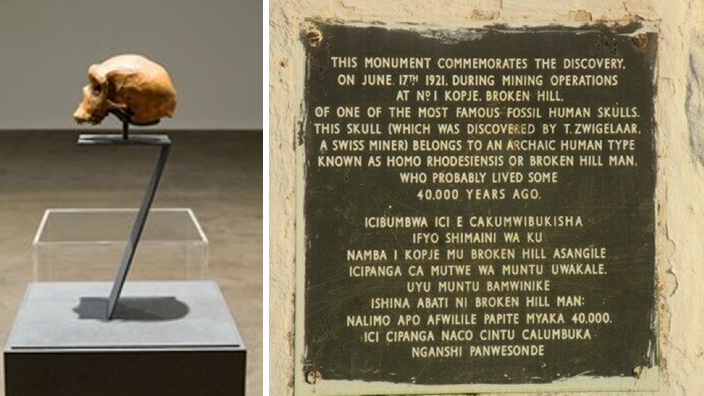

The Broken Hill Skull

On the first day, Zambia presented its case for the return of the Broken Hill Man Skull which was the first historically significant human fossil found in Africa when it was discovered in a mine in 1921. The skull was ‘donated’ by the Rhodesia Broken Hill Mine Company to the British Museum, but later transferred to the Natural History Museum. The skull is now on display in the Human Evolution Gallery of that museum.

Since the 1970s, the Zambian government has expressed a desire for the Broken Hill skull to be returned to its country of origin. In 2018, the fossil was discussed at the ICPRPC with the outcome that Zambia and the UK would pursue bilateral discussion. A spokesperson for the Museum Trustees added that the Museum “looks forward and is committed to constructive participation in this dialogue”.’

But the obstructive mindset of the UK side was not far from the surface. After the Zambian delegate explained the case of the skull and its immense cultural significance to his country, the UK representative, Rosie Weetch, the Head of Cultural Property at the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), and formerly a curator at the British Museum, proceeded to re-state the British position by repeating, in part, the British response back in 2018 which relevantly asserted that the museum is a public institution that operates with independence from Government and its collection is the property and responsibility of the Museum Trustees – not of the UK Government.

And for completeness, and this is not lost on the Greek delegation, Ms Weetch reminded the ICPRPC of the “strict legal constraints” on the powers of Trustees to give away, transfer or exchange items under the British Museum Act (which also governs the Natural History Museum).

Despite this, the UK representative added rather disingenuously that the UK “would like to engage in meaningful bilateral discussions”.

The ICPRPC Chair’s exasperation was palpable. He asked:

“What is the British position as opposed to the position of the Natural History Museum’s Board of Trustees? What are their criteria? The role of the ICPRCP is to look at best practices and in this spirit we need to see what is the best path for returning illicitly acquired objects. The Committee needs to enlarge its scope.”

Amongst interventions by other State members, Greece declared that it warmly supported the Zambian request and took the opportunity to remind the Committee that the ICPRCP is an intergovernmental committee which was established to deal with issues between member states and that they should not be delegated to issues between museums. In the words of the Greek representative:

“The UK Government cannot distance itself from the actions of the museum’s Board of Trustees. The use of legislative provisions to inhibit/prohibit the return of cultural property is unhelpful. Greece expects and wants tangible results.”

The Greek delegation further noted that the law was passed to protect the interests of the museum and in this case the skull had been taken by a colonial power.

The Case of the Parthenon Sculptures

On the second day of the ICPCRP Greece made its presentation via video conference from the Acropolis Museum in Athens. Its delegation comprised the new Director General of the Acropolis Museum, Nikolaos Stampolidis, the Secretary General of Culture, George Didaskalou, the Head of the Directorate of Documentation and Protection of Cultural Goods, Vasiliki Papageorgiou, and the experienced and highly-regarded legal advisor from the Special Legal Service of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Dr Artemis Papathanassiou.

The presentation was direct and to the point. The dismembered Parthenon Sculptures, split between London and Athens, must be reunited.

Dr Papathanassiou noted that the Greek request has been on the Committee’s agenda as a pending case since 1984. In 2013 Greece sought mediation but the British side emphatically refused to participate. The British government continues to claim that it is a matter for the British Museum Trustees and have relegated the case from intergovernmental to one between a State and a foreign institution or, alternatively, to an issue between museums. As Dr Papathanassiou stated, as far as international law is concerned, the obligation to return state cultural artefacts lies squarely on the government and not on a museum.

The Greek delegation also submitted that recent Ottoman archival scholarship and historical data indisputably prove that Elgin never obtained permission or approval to remove the sculptures so that they were never legally acquired as contended by the British Museum.

The Greek delegation was emphatic during its presentation:

1. The British side (that is to say, the British Museum Trustees) argue that UNESCO involvement in the matter is not the best way forward and therefore mediation held under the aegis of UNESCO would not carry the debate substantially forward.

2. One might reasonably wonder here why the British side does not agree to proceed to mediation if the legality of the British Museum’s ownership is as clear and uncontested as the British side claims it to be?

3. The unique wonder of the Parthenon Sculptures serves to refute the argument made by some museums that any legal decision to return them to Greece would be a precedent for emptying Western museums of cultural treasures, which have been looted or stolen or otherwise acquired under dubious circumstances.

4. The Greek response to this argument is that the Parthenon Sculptures differ from other museum objects in that they emanate from a surviving monument and their reunification to the parent structure would restore the integrity of a world heritage monument and would not create a precedent for other acts of return. The Parthenon is more than the symbol of Western Civilisation.

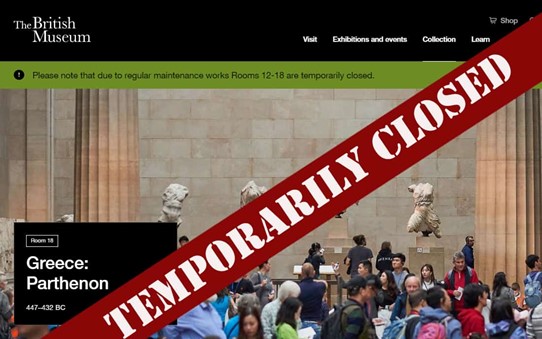

5. The British Museum states on its website that it “takes its commitment to be a world museum seriously”. If this is the case, may one ask the British why the Parthenon Gallery is closed to the public since the beginning of 2020, until further notice?

6. The sculptures can no longer remain imprisoned, waiting for the completion of the British Museum ‘Master Plan’. The British Museum, in any case, does not cover the necessary safety conditions of exposure. Is it raining again in the Parthenon Galleries?

7. For a museum to be able to boast that it is global or encyclopaedic it also must first teach ethos. The British Museum cannot do this with any kind of abductions or, even more so, with detachments from a global monument-symbol, such as the Parthenon.

8. By returning its members, its sculptures, to Greece, it could borrow (or be lent) works from Greece in order to display them in its galleries. And if it does the same with other works and antiquities to which there are claims, then it could be a museum of true world culture that presents artefacts from many cultures with the appropriate ethos, at the wish of the peoples who are owners of their cultural heritage.

9. The British contend that they believe that the British Museum is the best place for the Sculptures to be seen in the context of their rich contribution to the history of the whole of humanity. Despite the British Museum’s director’s description of Elgin’s actions as a “creative act”, the only truly creative act would be the return of the Sculptures to where they belong, to the Parthenon, the symbol of Western Civilisation.

10. For those who want the sculptures back in Athens, the Acropolis Museum’s top-floor Parthenon gallery is the perfect antidote to the dark Duveen gallery in the British Museum.

11. Despite repetition of well-known British arguments concerning Greece’s long standing just demand for rehabilitating a unique world heritage monument which remains a mutilated wonder of the world, Greece calls on the British government to reconsider their stand and to recognise, among other things, that the international claim for the restitution of the aesthetic, in principle, unity of the Parthenon outweighs any other possible counter arguments.

The UK response was sadly predictable.

The British delegate, Rosie Weetch, once again resorted to the well-worn arguments mounted by the British Museum in the past, even shamelessly re-reading a number of the talking points from the British submission made at the 2018 ICPRCP Session:

The UK Government notes the strong aspirations of the Greek Government to see all the surviving sculptures from the Parthenon reunified in the Acropolis Museum.

The Parthenon sculptures in the British Museum were legally acquired under the laws pertaining at the time and are legally owned by the Trustees of the Museum, which is independent of Government.

The Trustees of the British Museum believe that the Museum is the best place for the sculptures to be seen in the context of their rich contribution to the history of the whole of humanity. The British Museum is a world museum and millions of people from all over the world are able to visit the Museum free of charge.

The Trustees have never been asked for a loan of the Parthenon sculptures by the Greek Government, only for their permanent transfer to Athens. The Trustees will consider any request for any part of the collection to be borrowed and then returned, provided the borrowing institution acknowledges the British Museum’s ownership and that the normal loan conditions are satisfied.

Ms Weetch also claimed that the British Museum offers the “sense of a wider cultural context” for the sculptures and that it will continue to improve interpretation of the Parthenon Marbles in its collection. The British Museum, she claimed, is committed to “respectful collaboration” worldwide to the sharing and lending of the collection for the benefit of the widest possible audience to promote Ancient Greek culture.

ICPRCP Reaction

The Committee Chair wryly noted that the UK Government is quite clear in presenting the view of the Trustees of the British Museum and pointedly asked: “what is the government’s position?”

Other delegates expressed similar frustration. Egypt said it was striking to have a case with which the committee had been dealing since 1984 and urged that a strong decision was needed given the attitude displayed by the UK intervention. The sculptures were made by the Greeks in Greece to honour the Greeks. The claim that the British Museum is a “universal museum” was totally dangerous, according to the Egyptian delegate, as well as irrational and was equivalent to “what is mine is mine; what is yours is also mine and I have to show it to the world, including to you”.

The delegate from Zambia agreed and stressed that the Committee needed to take more drastic measures, calling for a “tough decision” to be given because of the repetitive UK arguments.

Italy said that it was time for a solution. This was also needed to lend momentum to the role and credibility of the ICPRCP, particularly as the claim by Greece goes to the issues of memory and identity and raises matters of diplomatic, historical and aesthetic significance, and not just legal.

Cameroon observed that the three cases before the ICPRCP from Greece, Zambia and Nigeria shared one thing in common, namely, an asymmetrical relationship in history where the artefacts were looted or otherwise obtained in a colonial context.

Palestine described the call for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures as a cri de coeur which stands out and calls for mediation between member states. The Palestinian delegate asked why the British Government had refused mediation.

Syria, as an observer state, declared that the Parthenon Sculptures belong to Greece and regretted that the negotiations are not going anywhere just as the role of the UK Government continues to be vague.

Cyprus joined the chorus and urged the ICPRCP Committee to comply with the will of Greece.

Greece responded that although the UK and Greek sides were working on a joint recommendation, it lamented the fact that since 1984 there had been sixteen separate recommendations adopted by the ICPRCP with no positive outcome. Greece urged the committee to take a decision for the return of specific cultural property, especially as Greece’s call back in 2013 for mediation and a productive dialogue for resolution of its just request had been rejected. Nothing is happening, lamented Artemis Papathanassiou.

Argentina urged the Committee to take a decision and stated that it supported Greece.

Egypt again intervened and declared that ICPRCP did not need a seventeenth identical recommendation and that it was time to take a firm stand. Egypt was not prepared to accept the British argument that it is for the British Museum to decide; the responsibility of the UK State is essential.

The Committee Chair, Mr Mosleh, at this point had heard enough, declaring that the case of the Parthenon Sculptures had inspired the Committee to look at the bigger picture and it was important not to dilute the case. He urged his colleagues to take a decision and pointedly added:

“I did not hear the UK position. I heard the British Museum Trustees’ position”.

The Chair concluded that the UNESCO Committee was supporting Greece.

And with that the 22nd Session of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee showed its hand and unanimously handed down Decision 22. COM 17 (sponsored by Zambia) which reads as follows:

- Recalling article 4 paragraphs 1 and 2 of the ICPRCP Statutes.

- Noting that the request for the Return of the Parthenon Sculptures is inscribed in its Agenda since 1984.

- Recalling its 16 Recommendations on the matter.

- Recalling further that the Parthenon is an emblematic monument of outstanding universal value inscribed in the World Heritage List.

- Aware of the legitimate and rightful demand of Greece.

- Acknowledging that Greece requested the UK in 2013 to enter into mediation in accordance to the UNESCO Rules of Procedure on Mediation and Conciliation.

- Recognising that the case has an intergovernmental character and, therefore, the obligation to return the Parthenon Sculptures lies squarely on the UK Government.

- Expresses its deep concern that the issue still remains pending.

- Expresses, further, its disappointment that its respective recommendations have not been observed by the UK.

- Expresses its strong conviction that states involved with return or restitution cases brought before the ICPRCP should make use of the UNESCO Mediation and Conciliation Procedures with a view to their resolution.

- Calls on the UK to reconsider its stand and proceed to a bona fide dialogue with Greece on the matter.

Conclusion

Although the ICPRCP is an advisory body, it is specifically clothed by UNESCO as its cultural heritage conscience.

The UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee expressly acknowledged the “legitimate and rightful demand” of Greece and after noting the unsuccessful attempts dating back to 2013 for mediation to take place under the auspices of UNESCO, it declared that this cultural dispute is and was intergovernmental in character and as a result the obligation to return the Parthenon Sculptures rests squarely on the United Kingdom.

According to some reports, the UK government was taken by surprise that the UNESCO committee handed down such a strongly-worded decision rather than merely adopting the usual recommendations of previous sessions. A government spokesperson was quoted as saying that the British side would challenge the decision because of issues “relating to fact and procedures with UNESCO” without specifying what they were.

And then, as if on autocue, the spokesperson continued:

“Our position is clear – the Parthenon Sculptures were acquired legally in accordance with the law at the time. The British Museum operates independently of the government and free from political interference. All decisions relating to collections are taken by the Museum’s trustees.”

This response, although entirely predictable, underscores what many have known for years. For almost four decades, culminating in the just-concluded 22nd Session of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee, the British side has displayed its utter contempt for the UNESCO process as well as its total lack of respect for Greece by failing to engage with the Greek side in any genuine attempt to find a resolution. The UK Government by its own submission made to the Paris conference made it abundantly clear that it is nothing more than a mouthpiece for the British Museum and seeks to avoid any meaningful and bona fide dialogue with Greece.

The time for more mutually respectful dialogue (for which some are still calling) is well and truly over. The contemptuous and disingenuous position adopted by the British side has put paid to that.

And, in any event, the current Conservative Government in Whitehall (beholden as it is to a colonialist-derived ‘retain and explain’ mindset) is most unlikely to change its position in what has clearly become a Cultural Groundhog Day.

Greece must now seize the day and use the considerable cultural diplomatic and soft power cache it has built up both within UNESCO and the General Assembly of the United Nations for an application to be made to the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion on the legal question of the return of culturally significant looted artefacts to their countries of origin.

Without such decisive action, nothing will change and the Parthenon Sculptures will remain locked away in the now closed Duveen Gallery of the British Museum.