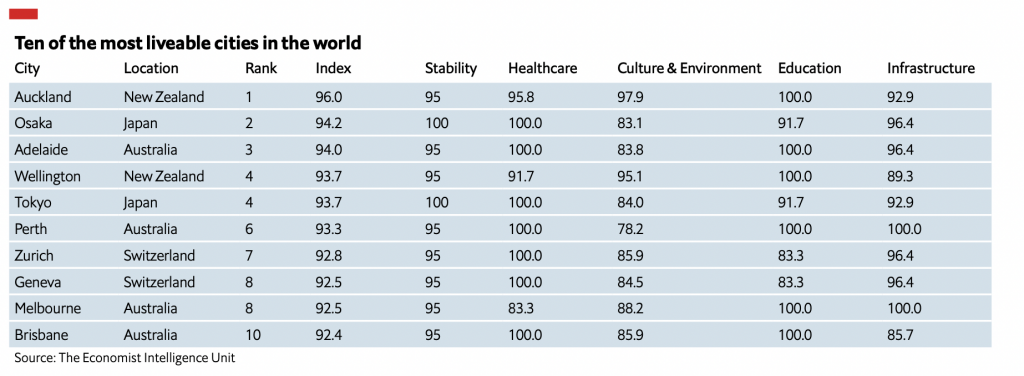

COVID-19 has shaken up the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) annual ranking of most liveable cities, propelling Auckland to first place, replacing Vienna, which crashed out of the top 10 as the island nations of New Zealand, Australia and Japan fared best.

The Austrian capital had led the list since 2018 and for years ran neck and neck with Melbourne at the top of the survey of 140 urban centres. New Zealand’s elimination of COVID-19 within its borders through lockdown measures helped by its geographic isolation, however, gave its cities a big boost

“New Zealand’s tough lockdown allowed their society to reopen and enabled citizens of cities like Auckland and Wellington to enjoy a lifestyle that looked similar to pre-pandemic life,” the EIU said in a statement.

Illustrating New Zealand’s advantage this year, Wellington also entered the top 10. It came fourth behind Osaka, which rose two spots to second place, and Adelaide, which leapfrogged its compatriots Sydney and Melbourne to third place from 10th.

The latest ranking is from 2019 as last year’s was cancelled.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a heavy toll on global liveability,” the EIU said.

“Cities across the world are now much less liveable than they were before the pandemic began, and we’ve seen that regions such as Europe have been hit particularly hard.”

According to the report, some countries among them Athens, continue to score poorly across the five categories.

“A consistently low stability score, owing to ongoing civil unrest and military conflicts, is the reason behind most of these cities featuring in the bottom ten. However, conditions have deteriorated even further as a result of Covid-19—particularly for healthcare,” reads the report.

The lower end of the rankings has seen less change, with the Syrian capital, Damascus, still the least liveable city in the world.