On Sunday, April 23 this year at the hall of the Cyprus Community of Sydney and NSW at 3pm, the former Premier of NSW and Australian Senator the Hon. Bob Carr, will launch the book authored by Professor Dr Anastasios M. Tamis entitled The Children of Aphrodite: The Story of Cypriots of Australia.

The event is organised by the Community of Cypriots within the framework of the Greek Festival of Sydney, and the presentation is under the auspices of the High Commissioner of the Republic of Cyprus in Australia, H.E. Antonis Sammoutis.

The biennial research and publication of the book is the result of the sponsorship of the Cyprus Community of Melbourne and Victoria. It is noted that the Cypriots of Sydney and greater NSW took an active part in the research and contributed in a useful and flawless way to the writing of the book.

The journey of the thousands of Cypriots who discovered Australia and settled in the Green Continent of the South, is described in the study that began in 2020 and was completed in 2021. The book describes the first Cypriot settlements, the first migration in the vast countryside but also in small and large urban centers, in every State of Australia. Their wandering in the forests and plantations, mines and factories is described. They are given the professions they practiced, the adventures they experienced, their achievements and their action. This is followed by their social organisation, their affiliation with unions, their work, their struggles to promote their cultural identity, the pain of colonialism that emerged from their island until 1960 and the 14 years of freedom.

The pioneering leaders, the people who served in the commons, their struggles are being mentioned. It describes the birth of their clubs, their contribution to Cyprus and Australia, their differences and disagreements, the divisions in difficult times. The chapters that follow describe the social and economic development of the Cypriots, the cultural constitution, the class of intellectuals, poets, writers, artists, people of letters and art, trade unionists, workers, relations with Greece and Cyprus, relations with Australia, and their struggles for the national aspiration and vision.

The history of the Cypriot settlement:

More than 150 years have passed since the pioneering Cypriots discovered Australia and almost 100 years since the appearance of their first collective organisations on the vast sugarcane and banana plantations in semitropical Far Queensland.

Young children who broke free from British schooners; inquisitive young people who longed for their adventure and fortune in countries that came out of myth; young children of large and destitute families who had to marry their sisters; destitute young people of large patriarchal families who escaped from the misery and poverty of their villages, to give hope to parents and other siblings left behind on the island; men who abandoned their wife and children to secure them later future and face in the sun; wives who scattered in search of a living in the vast countryside of Australia and stayed for ten and twenty years without seeing their wife and children again; young men, self-exiled of a difficult life and an incorrigible future. All victims of an open life, entangled with revolutions, uprisings, savage exploitation, deprivation and slavery, was the first settlement of the Cypriots of Australia from 1870 to 1930.

Then came the years of persecution, the stone face of the colonialists, the sullen face of the new oppressor, worse than that of the Ottoman that preceded it, a conquest which took the dimension of a sale. Thousands of Cypriots, Turks and Greeks escaped in the interwar period, when the first messages had appeared in the streets and mountains of the island, against the colonialists. However, already by the mid-1920s, the first organised assemblies had been set up and the informal organisations of the Cypriots in Northern Queensland were established.

Greek Cypriots had already purchased large areas, after hard work under the sun that burned the rails of the wagons carrying the sugar cane. They tore the old shirts and dressed the handfuls so that they would not be burned by the sun. They had already set up their first cooperatives and had jointly with partnership ventures bought the first farms, set up the first coffers in that vast countryside, the first bakeries, some had also carried their professions from Cyprus, blacksmith, barber, baker, tailor. Those who had no profession remained in the province, seeking asylum from their compatriots who were already landowners.

The most inquisitive sought their fortune in Brisbane, Perth, Adelaide, Sydney and some, fewer in Melbourne. There they were thrown into the business that did not require a good knowledge of English, nor large funds. They initially became wandering food distributors. They opened kiosks outside train stations, sold fresh fruit, bread in homes, fish in neighbourhoods, cold water in summer, candies at fairs. There after working for a few years for their survival, with a daily wage that counted 16 to 20 hours, in the kitchens of the cafes of their Greek compatriots, they then became kitschomans, then bought their own business, put a watch chain in the vest, wore a hat, left a mustache, wore a shiny pointed shoe, and took a picture next to the first limousines of the cities to send to their loved ones in Cyprus, together with cheques, the currency of hope, as it went down in history.

The war ensued. Thousands of Cypriots enlisted, served in the famous Regiment of Cypriots of the British Army, trained, and fought in Greece, Egypt and later in Italy. They were ordered by the colonialists, they say, as in 1916 in the First World War, their freedom, the right to decide, if they wanted, like the rest of the Aegean islanders to unite with Greece, to naturalise Greeks and not British. They believed it. They were deceived.

Immediately after the war, the mass exodus of Cypriot immigrants began after 1947. Thousands went out. Most in London and Birmingham and others in Australia. Most settled in Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide, Perth, Darwin, and others dispersed to vast Queensland. In the western suburbs of Melbourne and inland, in Sunshine and Brunswick most of them. Some, a few thousand, took refuge in the coal mines in the Latrobe Valley, and on the Winchelsea plateau, outside Geelong. They gathered here by the thousands and augmented. They mostly married other compatriots from their island (there were rarely extramarital affairs). Cypriots are like Kalymnians. They marry and marry only Cypriots, neither Kalamarades (they do not have much confidence in them), nor foreigners.

The indicator of in-breedings among Cypriots in Australia is the highest compared to any other part of Greece, except for the Kalymnians. Membership archives, and the interviews that took place in recent months, show that 69% of their children married a Cypriot (the general indicator among second generation of Greeks in 2011 was only 38%).

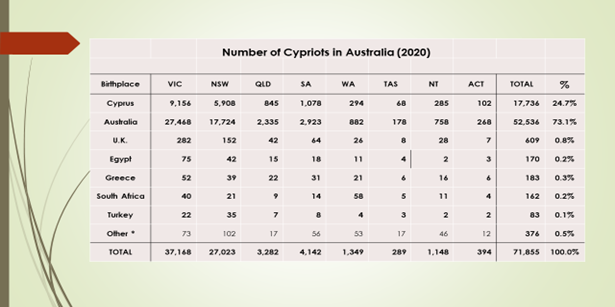

The number of Cypriots in Australia, based on the data of the official Census (2011 & 2016), as well as cross-checks of the variable factors, language, religion, and origin, is estimated at 72,000, of which 13,500 are Turkish Cypriots. Most of them are based in Melbourne, which is the ethnolinguistic centre of Hellenism in Australia.

The first organised settlements of the Cypriots took place in Queensland, where Cypriot Hellenism had settled there. 60% of Cypriots had settled in the provincial towns of Babinda, Home Hill, Ayr, Innisfail and Townsville where, since 1924, informal social organisations of Cypriots were already operating, in order to provide mutual assistance, shelter and work. The fact that they were British nationals gave them the right to equal treatment with Anglo-Australians in finding work and the favourable bias.

In many cases, during the difficult years of economic crises and unemployment, many Cypriots accompanied Greek settlers of the time and on the grounds that they were “Cypriots” the employers provided them with work. “Cypriot camouflage” operated even until the 1960s in most Australian states. The informal Cypriot organisations of the province of Queensland, such as that of Home Hill, while initially operating as a Cypriot organisation and founding the church of St Stephen in the early 1930s, later turned into a Greek Community.

The legally established Cypriot Communities were organised in the 1930s in Melbourne, Brisbane and Sydney and a little later in Adelaide. The cause of the founding of the Communities and the social and political rally was the October revolt of the Cypriots in 1931 against the colonialists, but also the deep economic crisis that had wreaked poverty and havoc on hundreds of Cypriot families. It should be noted that at that time community affairs, as well as ecclesiastical and political affairs, were regulated almost exclusively by the economic and social elite of Cypriots and Greeks.

There were those few businessmen, restaurant owners and cafés, mainly landowners with active participation in the early societies of urban cities, who had reason and opinion. Most Greeks and Cypriots were proletarians and peasants. The front-runners were absent, the educated, the professionals. The vast proletariat functioned, without a middle class, without a social backbone, without a bourgeoisie. This social elite laid the foundations for the Cypriot era, created the conditions for the existence of the first clubs that all bore the names of Cypriot heroes from antiquity, and anxiously awaited the arrival of the main body of the Cypriot exodus after 1947.

With the arrival of thousands of Cypriot settlers (they were not counted as immigrants, but as settlers, like British nationals), a strong division arose between the progressive forces that in their majority constituted the new settlers and the conservatives of the pre-war period. The causes that created intense competition and division were many. Initially there was a conflict between old and new Cypriot settlers. Post-war settlers often complained about the lack of protection and care they received from the old ones. Then there was the suspicion aroused against all those who had served in the British Army and had collaborated with the colonialists. After 1955, the liberation struggle reaped these differences.

The EOKA fighters were considered by the Australian establishment, as well as by the British, as “terrorists”, which caused rifts in the intra-community relations of the Cypriots of Australia. This was followed by the intense rupture, the mother of all divisions, the civil war climate of Greece. The leftists and friends of AKEL, the workers’ and peasant proletariat against the conservative forces. When this turned, just before 1960, into a deep and partisan rift between the progressives who raised the flag of the independence of Cyprus and the conservative patriots who supported the Union with Greece, then organisations split, new organisations emerged, and the division even took on the domestic dimension.

The events of 1963-1964, although they initially rallied the Cypriot settlers of Australia, nevertheless caused new ideological conflicts and a new division, expressed after the coup d’état of the Junta and the invasion of the Turks, as “guarantors” of the security of the Turkish Cypriots, whom, however, over the next twenty years they were able to “self-exile” in all the neighborhoods of the world and replace them with settlers of Anatolia.

The two decades that followed 1974-1994 were among the most difficult in the history of the settlement of Cypriots throughout the Diaspora. New clubs were founded because the progressives “blocked” any attempt from the conservative candidates to win even one election. When this was understood, namely that conservatives had no hope of governing the old historical organisations, new associations were founded, “philhellenic” (the term is used in the sense of one who is devoted to the Union with Greece), new clubs were born as Lesches, even as informal organisations. In the end, the Lesches, which were also the opposing ideological awe for the communities, not only did not hurt the communal cause since their leaders were also ardent patriots and anxious to make the other side, the other voice, heard, they too filled the gap and kept their members close to Cyprus. Only the Sydney Club remained alive in the years that followed, mainly because of its large land displacement.

After 1990, the regional Communities of Greeks were established in all major urban centers of Australia, but mainly in Melbourne, where a total of nine organisations operated. Their contribution was very important and remarkable and this is because they did not “step,” did not “intrude,” did not destroy services that were already operating, ministries already offered by the historical community of Cypriots. They caused new openings, turned to social welfare, created nursing homes, welfare centers, schools and sports clubs and thus complemented the offer to society and members. Thus, the offer of the organised Cypriots to the approximately 40,000 Cypriots of Melbourne was completed.

After 2000, many of the children of the first Cypriot settlers came to power. They took up leadership positions, took part in decisions in a Cypriot community where 92% of their members were born in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. The inexorable time by now flattened the first generation of settlers. The leaders who had set up the infrastructure have either passed away, or remained helpless in homes and social institutions. The needs of the past do not work. The mutual help, the finding of work, the memory of the village, the need for coexistence and social gathering and common participation ceased to have their old color. The preservation of tradition, customs, cultural heritage, language, and dialects remain the “signs” of navigation, but as cultural events, not as a way of life, as it was in the past.

Book of historical memory:

The President of the Cypriots of Melbourne, Former Minister, Mr Theofanis Theophanous, said: “This book authored by Professor Anastasios Tamis is a historical milestone of remembrance and evaluation. As president and representing the members of my Board of Directors, I declare that this story must enter all the homes of Cypriots, in order to remind their children and grandchildren of the struggle and anguish of the pioneers, the sacrifices of their fathers and grandfathers and to show them their own responsibility towards their identity, but also their debt to our martyred little Great Homeland that is under foreign occupation, captive and bleeding.”

The book will also be presented in Nicosia in August at the initiative of the Australian Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a gift-sample of the cooperation between Australians and Cypriots, within the framework of 50 years of diplomatic relations between Cyprus and Australia.

“It is our pleasure and honour to present this book in Sydney and in this way to honour the memory and sacrifices of the pioneering Cypriots of Australia, who laid the foundations of an organised Cypriot presence in Australia,” the President of the Cyprus Community of Sydney, Mr Andrew Costa, said.

Dr Tamis said: “I thank from the bottom of my heart all those who contributed to the publication of the book. I am fully pleased with the organisation of the presentation of the book by the Cyprus Community of Sydney within the framework of the Greek Festival of Sydney and I am grateful to all those who helped in the research of this book, which is being passed on to future generations of Cypriots as a book of historical reference.”