By Dr Michael Bendon.

“I’m not so much worried about that bullet with my name on it as all those unaddressed ones flying around” – R. H. Smith (NX2040).

From the battles fought in Greece and Crete come stories of Australians who, after the failed campaigns, avoided capture and joined with local resistance to continue the struggle against the Germans. Tales of people’s bravery and sacrifice, continuing over the years right up until the defeat of Nazi Germany, have long been presented in official histories and personal accounts.

So often there seems to be an element of luck or chance underpinning the courageous exploits of these evaders. The toss of a coin, the turn of a guard’s eye, a moment of indecision or just being in the right or wrong place at the right or wrong time would have, so many times, contributed to the success or failure of an escape and subsequent evasion or even a mission and its intended outcome.

READ MORE: Private Ross Hamilton Smith’s unusual reunion with his wartime diary from Greece.

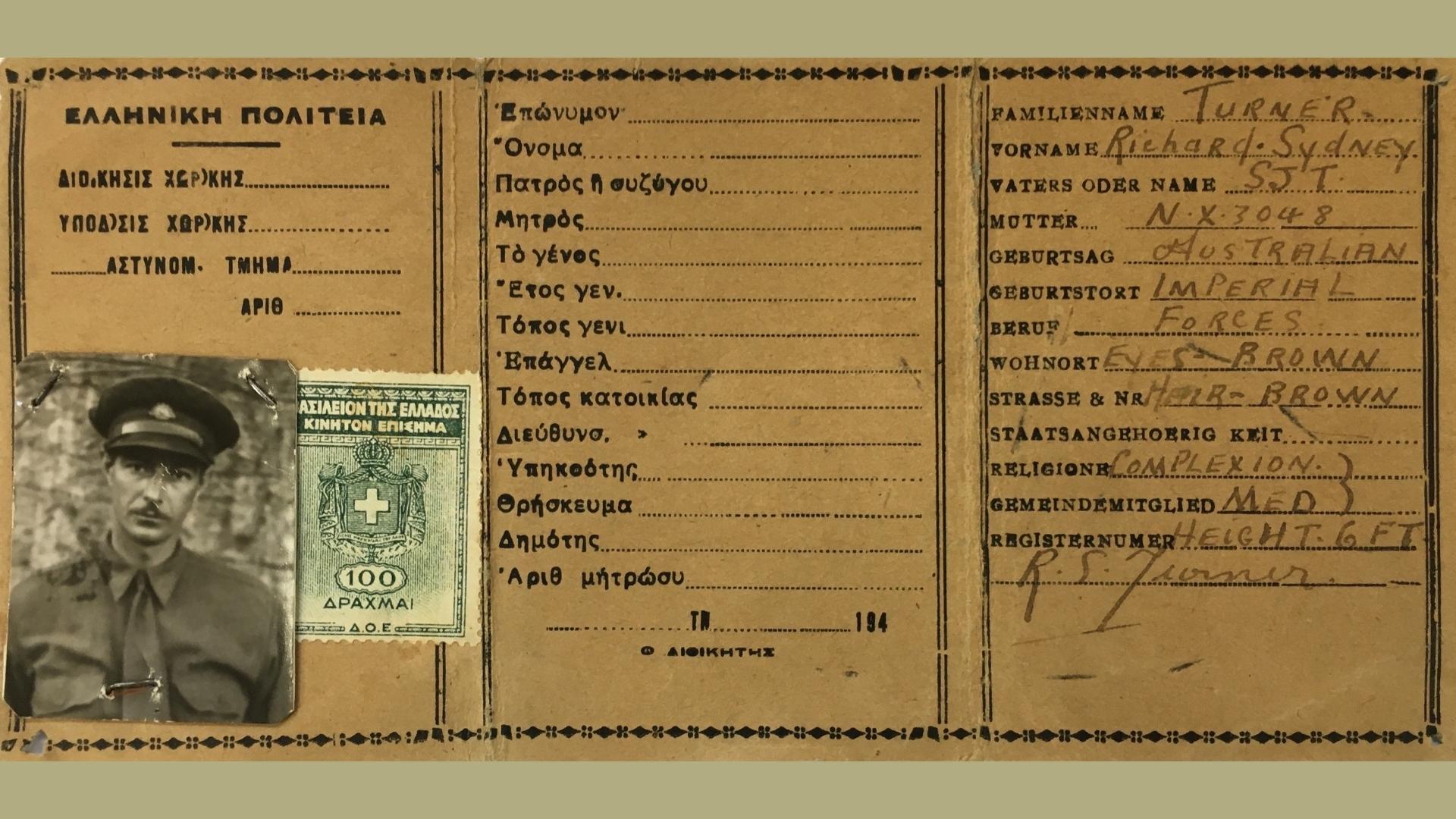

One unfortunate story concerns the untimely death of Sergeant Richard Sydney Turner (NX3048). Turner’s life was brought to an abrupt end on the way to the aerodrome at Kalmaki for the next leg of his journey home to Sydney. After more than three intrepid and dangerous years with the resistance in mainland Greece, recognised in part by the award of the Military Medal, his life ended in an Athens street under a hail of gun fire on Sunday 17th December 1944.

Turner was a member of Headquarters Australian Army Service Corps (HQ AASC), embarking for Greece with that unit in the second week of April 1941. However, the tide of the battle turned against the ANZACs and less than three weeks later he found himself waiting near Corinth with thousands of others for transport back to Alexandria.

READ MORE: ‘Irrepressible those Aussies. Glad they’re on our side’: John Digby Sutton in Greece and Crete 1941.

As at many of the evacuation points along the southern coast, orders to prepare to embark were issued only to be rescinded when insufficient ships were available. It soon became obvious that as the invading Germans rapidly approached, it was something like every man for himself. Some took to the mountains while others fashioned makeshift rafts in attempts to avoid capture while the greater majority became prisoners of war. Turner’s service record shows him officially reported as missing in Greece on June 3, with the presumption of him being a POW added some two weeks later.

Turner was able to hide successfully for over a month until he was captured in early June. He was sent to a holding camp before being loaded onto a northbound train for Germany. The train was forced to halt its journey as much of the line had been destroyed by retreating allied soldiers. The prisoners were offloaded to march in long columns to where they could once again pick up a train. A number of Australians took the opportunity to make good their escape, Turner among them. For quite a few weeks, Turner and his group of escapees were able to avoid the German patrols with the help of local Greek villagers. Then, with the arrival of further occupation forces, large rewards were offered to flush out any allied soldiers making it impossible to continue endangering the people who were assisting them.

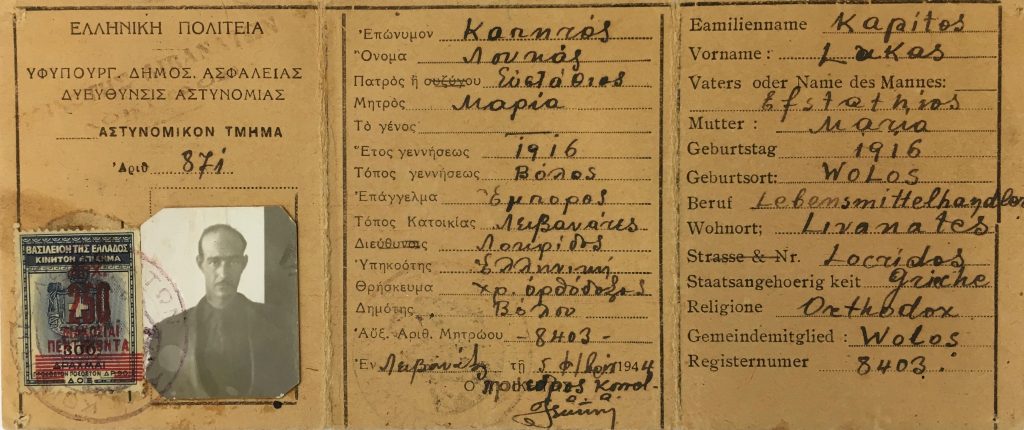

The group, by necessity, splintered further, with Turner and his friend able to remain on the run throughout the first winter living in caves and even, apparently, inside a hollow tree for several weeks. After the capture of his companion and extended bouts of severe hunger and sickness, Turner often considered giving up. Fortunately, Ioannis Kallinikas, a local villager found Turner and sheltered him, at great personal risk, over the next eighteen months.

READ MORE: Part 2: In Greece and Crete with John Digby Sutton.

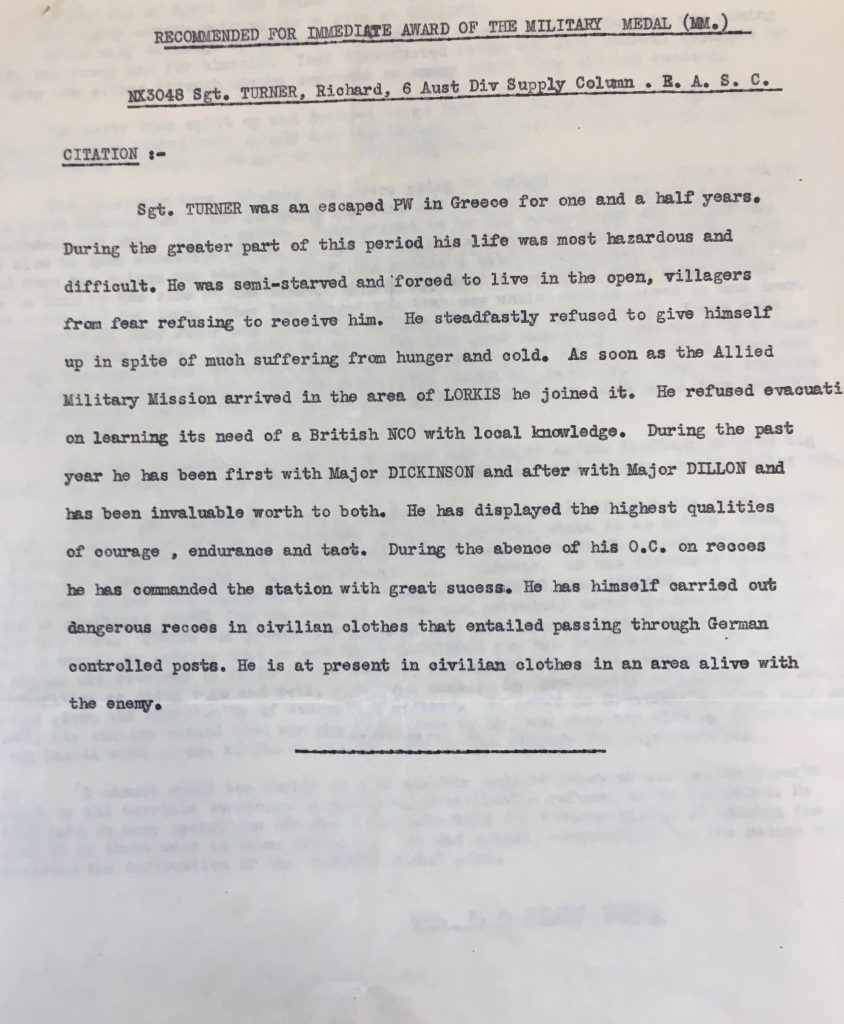

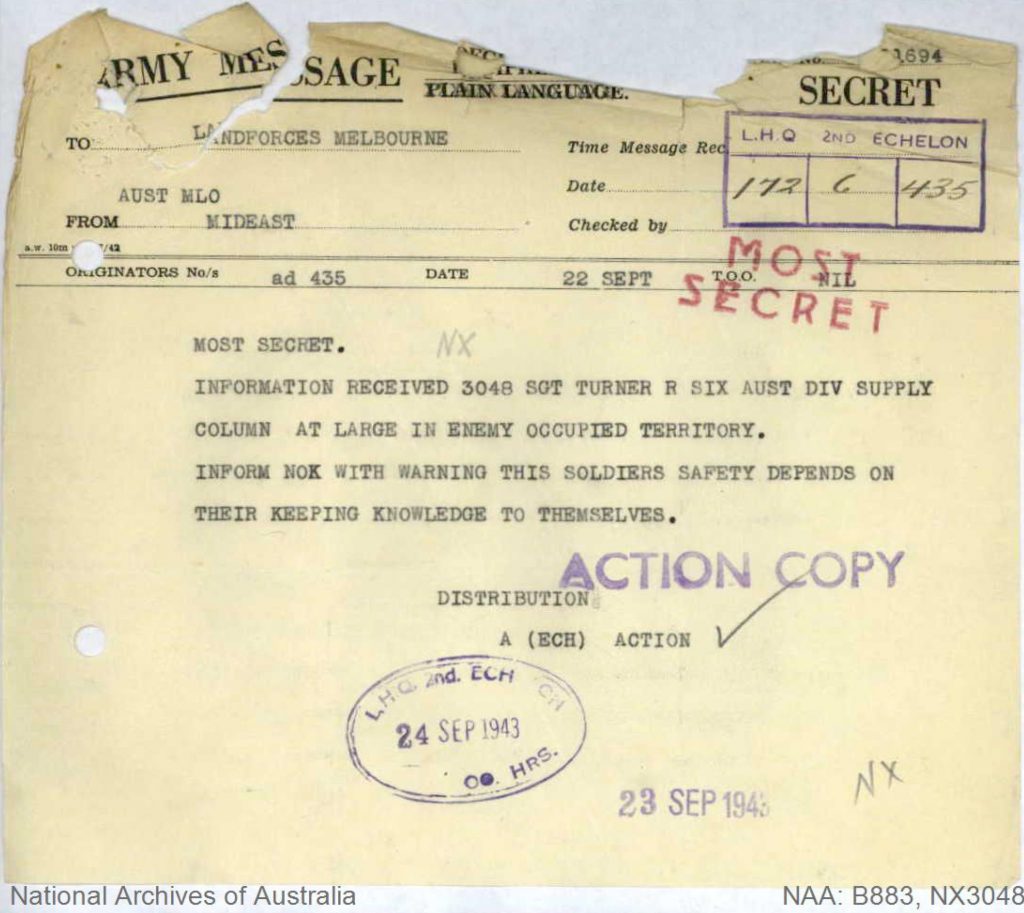

With the summer of 1943 approaching, organised Greek resistance to the occupation expanded into the area where Turner was hiding. He joined the guerrillas (Andartes) and began to travel with them. It was around this time that he met with a British liaison officer, Major Dickinson, who was helping support the movement. Through Dickinson a message was sent to inform Cairo that after having been listed as missing for well over two years, Richard Sydney Turner was alive and well. Turner’s service record, held by the National Archives, contains some of the correspondence related to his freedom in the Greek mountains although one particular letter incorrectly places Turner at liberty on Crete.

Turner, described by certain British officers as ‘a warrior type,’ continued to fight with the resistance group even though under threat of immediate execution if he were to be caught in civilian clothes – a spy. When offered a chance to return home in 1944 he refused, reputedly responding, ‘I shall stay on as long as I can be useful to the Greeks; they need all their friends. I like the Greeks; I have eaten frogs and tortoises with them and have starved with them.’

READ MORE: Uncovering the secrets of the Forgotten Flotilla off the coast of western Crete.

Very soon after this initial offer of home leave, Turner received orders to return to Australia. He reluctantly complied. At this point in late 1944, the Axis forces had withdrawn but the country now faced the growing threat of civil war, a fight to fill the power vacuum.

The outer suburbs of Athens had been overtaken by Communist fighters in early December. As he prepared to leave Greece, there is a story told that over farewell drinks with the Australian war correspondent Keith Hooper, Turner laughed and joked about the increasing violence of insurgents on the outskirts of the city, ‘I suppose it’d be just a man’s luck to get himself bumped off.’

Unfortunately, whether or not Turner actually inadvertently predicted his demise, the very next morning as the truck carrying the courageous Australian to his plane home passed the brewery of the local beer Fix, it was raked with machine gun fire. The insurgents had set themselves atop that building. Richard Turner, at 28 years of age, was the only occupant to die, with an English officer, another passenger, wounded.

Richard Sydney Turner was awarded the Military Medal for his service and achievements in Greece.

READ MORE: A story told is a life lived: The Battle of Crete.