By Dr Michael Bendon.

Last week I introduced the reader to John Digby Sutton DSO in an attempt to provide something of an introduction to just one of the people who gave all they possibly could during the Greek Campaign and the Battle of Crete in 1941.

John is by no means the only unsung hero or heroine of those campaigns but hopefully as you read you will come to realise the great importance of individuals and their untold, selfless contributions in those Mediterranean campaigns. Therein lies a dedication to not only friends and family but to a country and its freedom. Perhaps in your family there is such a person so please keep in mind always – A story told is a life lived. Lest we forget.

READ MORE: ‘Irrepressible those Aussies. Glad they’re on our side’: John Digby Sutton in Greece and Crete 1941.

Prior to actually knowing John was still alive, I had come across his name occasionally and also his vessel mentioned a number of times in official records. However, it was only then a name, nothing more of substance.

Through the times I was able to spend with John before his passing in 2017, I learned much about his life during and indeed after the war, ‘that best portion of a good man’s life: his little nameless, unremembered acts of kindness and love.’ (William Wordsworth). John added a personal dimension to these campaigns with the involvement of his craft in the saving of thousands of British, Australian and New Zealand troops.

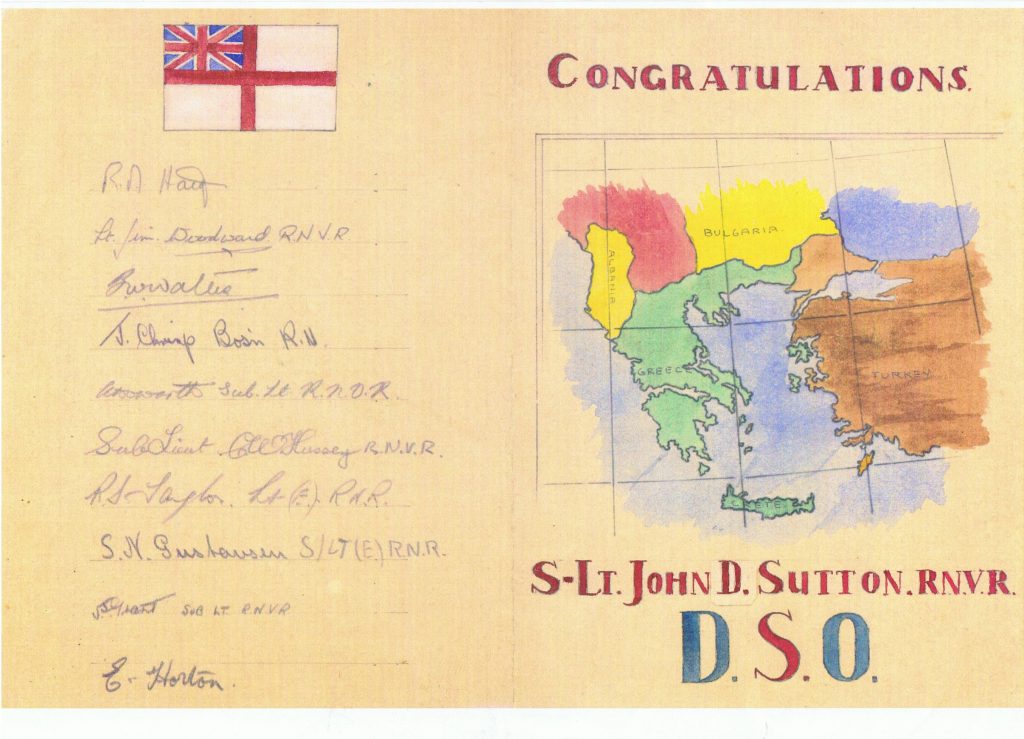

For his work in the Greek campaign, John was awarded a DSO – a somewhat unusual award for this period of the war considering his rank, Temporary Sub-Lieutenant in the RNVR (Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve), and barely twenty-two years of age. The Distinguished Service Order of World War Two seems to have been usually awarded to those of higher rank, so much so that when searching an internet list of those DSOs awarded, John Digby Sutton had not been included. That oversight has since been adjusted.

READ MORE: Uncovering the secrets of the Forgotten Flotilla off the coast of western Crete.

John’s DSO commendation is somewhat vague as to the specific event for which the award was made although it is more than likely the time,

“when 450 troops were left behind on the beach he ferried them to Zea Island, and took them to transports at Raphtis the following night. He eventually brought his craft safely to Souda Bay. Had he not concealed his craft so successfully during the day and shown initiative, courage and good judgement, there would have been many troops left behind. (The National Archives, Kew: ADM 1/11490)“

To expand on this particular event for the reader will better set the context. John had been into the beach that night already a number of times ferrying over two thousand people to safety. The skipper, in consultation with his number two, Jack, agreed that they could not leave troops stranded for another day. They decided on one last trip in, even though they knew only too well that the deadline to be out of range of the Luftwaffe by daylight would very soon be upon them.

Jack raced up to the wheelhouse: ‘Looks like around 450 plus a postman and a dog. Let’s go.’ John raced the engine and headed out for the rendezvous point and to the ships to pick up the weary troops.

READ MORE: A story told is a life lived: The Battle of Crete.

I asked how long it took to get out to the ships. ‘Oh about an hour and a half,’ answered John, ‘and then we spent another hour looking for them but they had already buggered off.’

John continued: ‘Here’s me a little Sub-Lieutenant sure that I have the right point to meet the ships, but doubt crept in as those ships probably carried Admirals and the like. I must have gotten it wrong.’

But John was not mistaken. The ships had indeed left to beat the fast approaching dawn, leaving John with 450 souls aboard, actually 452 as we must include the postman and the dog. The young skipper decided to take his passengers to Kea Island some 35 kilometres distant and hide up until the following night. He was able to successfully deliver the troops the next evening before once again continuing his ferrying operations for the beaches.

When finally the evacuation was halted, John, in command of the only TLC remaining afloat from the original five sent up to assist, headed back towards Souda Bay. On the way there, they came across a caique loaded with refugees and troops from the battered Greece. Behind the small fishing vessel was a whaler, a ship’s boat, from an ill-fated destroyer. In the boat were some of the very few survivors of the disaster involving SS Slamat, a Dutch transport helping with the evacuation. Laden with troops, Slamat was hit and sunk by bombers just off the coast. Two destroyers, Wryneck and Diamond, sent to gather survivors were also sunk with less than 30 survivors, passengers and crew, from all three vessels. A great tragedy. John took the hapless group in tow and back to Crete.

Over the next four weeks, TLC A6 under John’s command, continued work in Souda Bay loading and offloading as well as making a number of trips along the northern coast to deliver tanks and supplies to Heraklion and Rethymno. There was not one of these voyages where the slow moving, under-armed craft was not attacked, machine-gunned and/or bombed.

As the reader likely knows, the Germans quickly overran the island after their airborne invasion began on May 20th and very soon the headquarters at Souda was threatened. John’s craft and another TLC were ordered around to Sphakia to once more assist with the evacuation of troops. A6 stopped at Souda Island on the way out to pick up wounded members of a New Zealand machine gun battalion manning the boom defence. He also pulled in a Maleme under heavy fire to pick up some stranded Australians who had signalled from their hiding place on the shore.

While hiding that next morning awaiting the darkness to continue onto Sphakia, the craft was spotted by the Luftwaffe sheltering near the high cliffs of Phalasarna. Stuka dive-bombers were dispatched and they were able to sink the TLC. John, his crew and his passengers were safely holed up in nearby caves but were soon after captured by the German patrols swarming over the area.

John Digby Sutton’s wartime action lasted less than two months but, in that short time, the young skipper was awarded the second highest honour for bravery, the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) as well as being Mentioned in Dispatches (MID) for his work along the northern coast of Crete.