By Dr Michael Bendon.

War, and the upheaval and havoc it wreaks on all people involved, may be difficult to imagine for a great many of us. However, rising from the heartbreak and destruction are thousands of untold stories of people, of friendship, of strange antics and of unrivalled heroism. Some, when removed from the framework of horror, are tales that may prove amusing and often surprising.

READ MORE: A story told is a life lived: The Battle of Crete.

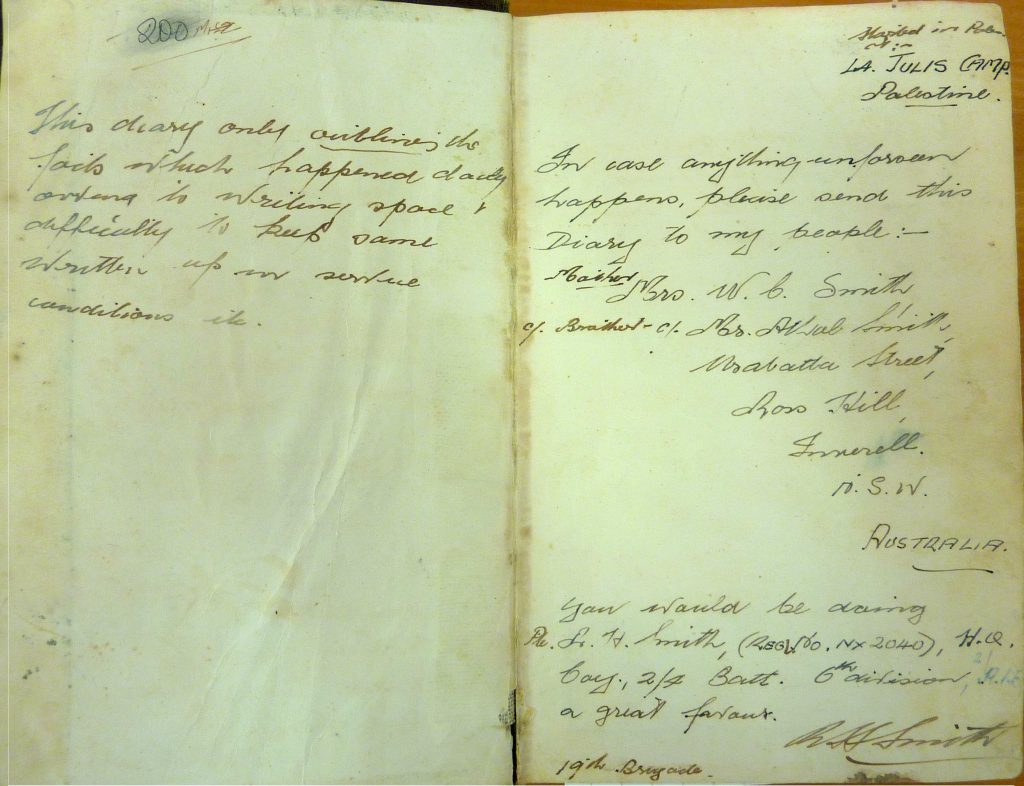

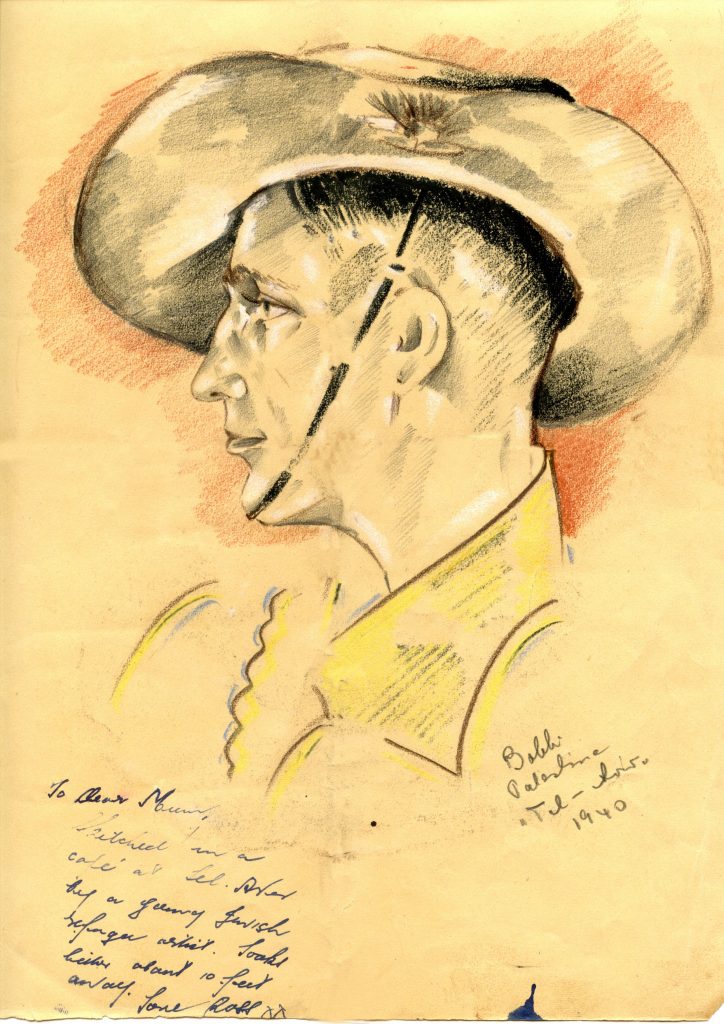

One such story, that in itself becomes something of a saga, revolves around a wartime diary and a reunion with its original owner, Private Ross Hamilton Smith of Inverell, New South Wales. Ross volunteered for the AIF in 1939 and soon found himself on the way to the Middle East as a member of the 2/4th Infantry Battalion. There in Palestine, his battalion along with numerous other units, underwent intensive training as part of the 6th Division.

The division then took part in the action during the campaign in the Western Desert. In March of 1941, with the situation in Greece rapidly escalating, the 6th and 7th Divisions were moved back in preparation for embarkation to assist the Greeks in their battle against the invading Italians and Germans.

READ MORE: Uncovering the secrets of the Forgotten Flotilla off the coast of western Crete.

From the very day Ross first enlisted for Australia, he had maintained a detailed personal diary, with every day, eventful or otherwise, recorded. In fact, Ross was quite prolific when it came to his writing and his musings, as along with the diary of this particular story, he proved to be a very dutiful and expressive correspondent, sending hundreds of letters home during his time overseas.

When the time came for the move towards Alexandria to board troopships for mainland Greece, the order came through that all personal diaries and remaining cameras were to be handed in and sent to safe storage in the kit store. Strangely and unexplainedly, Ross’s diary, after collection and packing in Mersah Matruh, began its most unusual journey. Instead of being transported to battalion stores as was intended, the diary somehow made its way to Alexandria with the equipment that was to accompany the battalion to Greece.

While fighting in Greece, Ross never realised that his precious diary had also made the trip across the Mediterranean and, quite possibly, aboard the same ship. When the battle reached a point where Allied commanders believed nothing further could be done and the order to withdraw was given, tonnes and tonnes of supplies were discarded. Likely right at the bottom of a box, perhaps concealed under layers of tins of bully beef, lay Ross’ diary.

The small black leather-covered diary had already ‘stowed away’ to follow its dedicated owner into battle. Then, with the destruction of much of the stores during the evacuation, the book detailing over a year in the writer’s young life miraculously avoided the fiery fate meted out to the greater majority of provisions and equipment.

READ MORE: ‘Irrepressible those Aussies. Glad they’re on our side’: John Digby Sutton in Greece and Crete 1941.

Ross was evacuated from Greece along with others in his battalion boarding the ill-fated Dutch transport Costa Rica. A letter written home soon after his safe arrival in Palestine details the sinking of the vessel.

‘We got away from a port right in the south of Greece at about 3.30am on the Costa Rica. Just after daylight we got a hell of a shock when the air raid alarm went. Jerry had got through and let go a beauty and hit us. Started immediately to go down by the stern; lights failed and water rushed into the engine room. There was no panic. There were 2500 troops and we all lined up on deck. No one was allowed below. I wanted to get my haversack with writing outfit and fountain pen, my rifle and equipment. But no, it just had to go down to Davy Jones’ locker.‘

The letter also explains how the rescued troops were transferred safely to destroyers and ferried to Crete rather than to Alexandria as they had believed to be their destination. The tone of the letter though seems to indicate that 20-year-old Ross took it all in his young stride.

‘When we were all off, one destroyer stayed behind to slip a torpedo or two into the stricken ship and we were off at a fast clip for Crete. We were originally on our way to Alexandria and two other ships went there without mishap. Wasn’t I lucky? I would have missed the business in Crete, but now that I am safely through it, I am glad I went there and got an insight into parachute troops and their workings.’

Ross leaves the Middle East mid-February 1942 to return to Australia after some 800 days abroad. His remaining time in the Army is spent in Australia in various units and undergoing further training. He was demobilised as of 25th October 1945, returning home to Inverell. However, the saga of Ross’ missing diary was yet to really take shape.

READ MORE: Part 2: In Greece and Crete with John Digby Sutton.

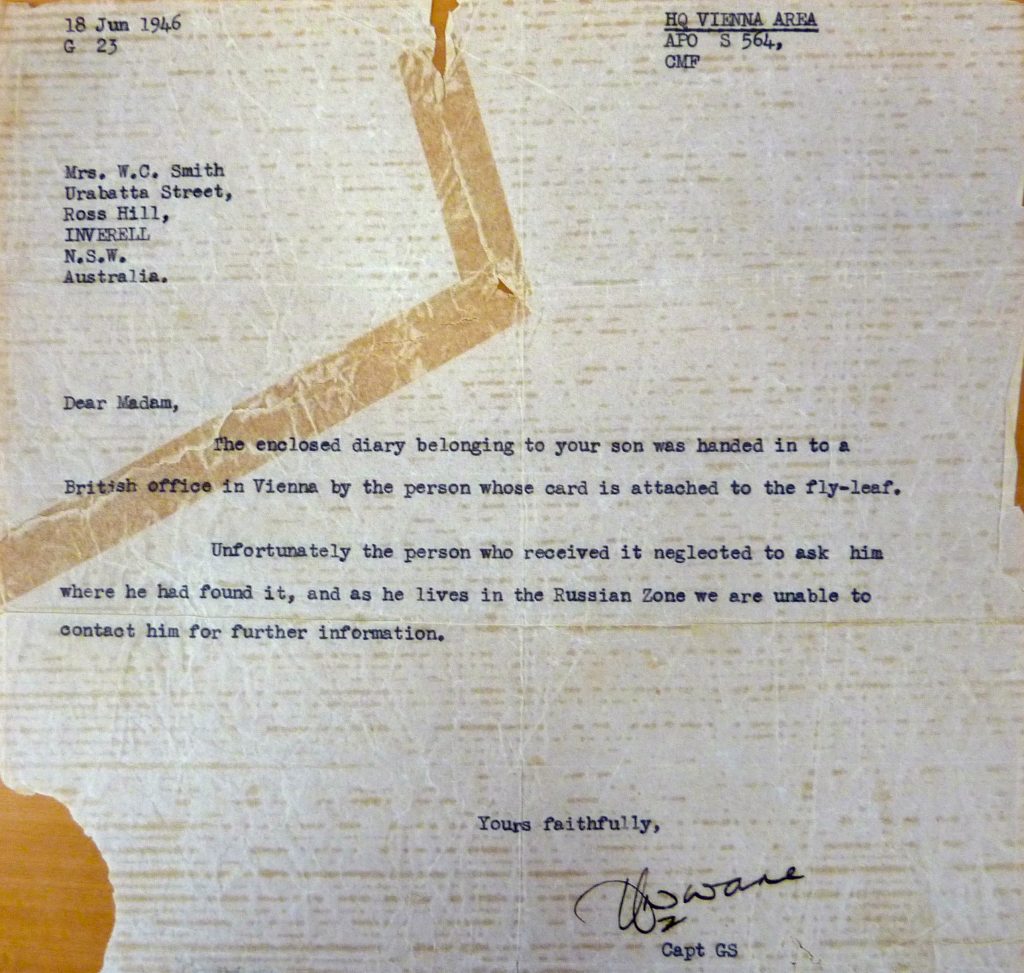

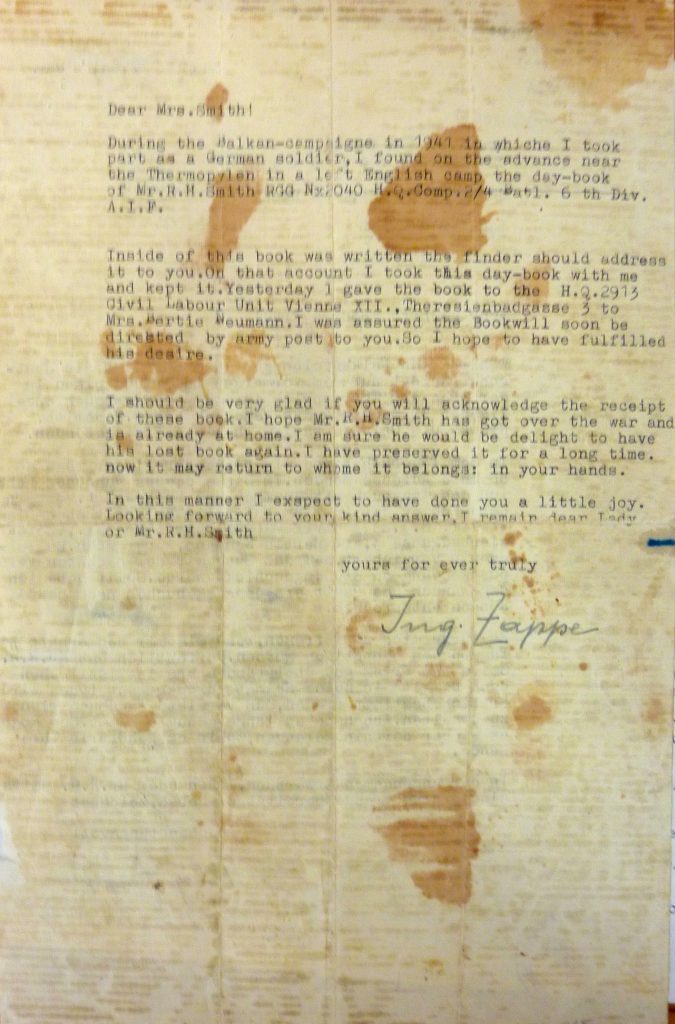

Almost a year had passed when a letter arrived addressed to Ross’ mother. The sender was one Josef Zappe, apparently an Austrian engineer. During the Greek campaign he had served with the German Army. Enclosed was an explanatory letter to say that Ross’ long lost and all-but-forgotten diary had been delivered to a British office in Vienna.

Zappe had also written a letter to accompany the diary in which he explained how he had stumbled across the journal when advancing through a deserted camp near Thermopylae. There he had opened the diary to the first page and saw Ross’ hopeful request for the return of his property should it have become separated from him.

Although Zappe writes little more in his letter other than his chance discovery of such a personal item, it is very interesting to think that the finder likely decided at the very time of the discovery to attempt one day to return the diary to its rightful owner. Even though the book is small and its weight negligible, any added burden to a field pack in times of war would have to have been very carefully considered and prioritised.

During his time in Greece and then in Crete, Ross continued to add to his extensive writings with a new diary, notebook and letters to his family and friends. His ideas, his hopes, his fears and his observations of the Greek and Cretan campaigns are fortunately preserved, or at least for the most part.

*All photographic and documentary materials used within this article are provided with the kind permission of Ross’ immediate family. They remain under copyright and may not be reused in any format without the express consent of Ross’ family.