By George Vardas, Kytherian World Heritage Fund.

“The worst thing was … how they screamed every night at midnight. I do not know why they started screaming. We were in the harbour and they were on the pier and at midnight they started screaming” – Ernest Hemingway, On the Quai at Smyrna (1922).

“The Smyrna affair, which far outweighs the horrors of the First World War or even the present one, has been somehow soft-pedalled and almost expunged from the memory of present-day man” – Henry Miller, The Colossus of Maroussi (1942).

In 2022, we honour the 100th anniversary of the formation of the Kytherian Brotherhood of Australia.

But a century ago in 1922 unspeakable horrors were unleashed upon the Greek and Armenian populations of the famous and vibrant Turkish port city of Smyrna in what is now commonly known as the Smyrna Catastrophe.

This essay is dedicated to the memory of the Kytherian diaspora of Smyrna and Asia Minor, a paradise lost. [1]

By the early part of the 20th century, Smyrna had grown into one of the largest, richest and most cosmopolitan cities in the Mediterranean, with large Greek, Armenian and Jewish populations. Smyrna was described by the British writer Norman Douglas as the “most enjoyable place on earth” and was in fact a city of tolerance. Its imposing quayside or promenade was famous throughout the Levantine world.

But the Smyrna quay was also known as “Tsirigotika” because of the presence of many Kytherians.

Kytherians first turned up in Smyrna in the latter half of the eighteenth century. The first major wave of Kytherian migration occurred around 1850 after the agricultural devastation in most crops and vines experienced on the island and continued until the late 1890s when Kytherians started to look towards America and then Australia as more suitable destinations. Travel to Smyrna was facilitated by the establishment of a direct and frequent passenger connection between Trieste to Smyrna, stopping over in Kythera. [2]

Smyrna was an attractive immigration destination, in contrast to America or Australia, since the city was primarily in economic prosperity and there the Kytherian immigrants felt more comfortable, as they did not need to learn another language and were more easily able to maintain their religion, customs and traditions. [3]

Many started out as sharecroppers and farm workers before moving on. Others found work as servants in British or Greek households. As a Kytherian middle class grew, their numbers included lawyers, doctors, teachers, artists, ministers of religion, architects, bankers, merchants, landowners, wine makers, business proprietors and shipowners. It is estimated that there were approximately 25,000 Kytherian emigrants out of a total Greek population in Smyrna of at least 350,000 before the fall of the city.

Kytherians represented the most numerous and distinct group among the Greek Orthodox population of Smyrna. The Kytherian immigrants retained their local identity and group coherence despite the distance that separated them from their place of origin through collective action and religious and spiritual connections. [4]

Because of the large Greek presence Smyrna was known by the Turks as Giaour Izmir (Smyrna the Infidel) whereas the cosmopolitan Greeks and other nationalities in this Levantine city happily described it as the Fleur de ‘Ionie (Flower of Ionian). According to some Kytherians, such as Dimitri Argyropoulos, the bustling port city was “both the Europe of the Orient and the Orient of Europe”.

Kytherians occupied various parts of the city and surrounding suburbs, including Koukloutzas, Bournova, Mersinli, Pappa-Scala (“Priest’s Steps”) and Gioul Bahtse (“Nice Garden”). They were generally regarded as one of the largest and most cohesive groups within Smyrna’s Greek Orthodox community.

The Kytherian community in Smyrna was able to maintain its local identity despite the tyranny of distance from Cerigo (as the island was originally known from Venetian times and during the period of the British Protectorate of the Ionian Islands up until 1864).

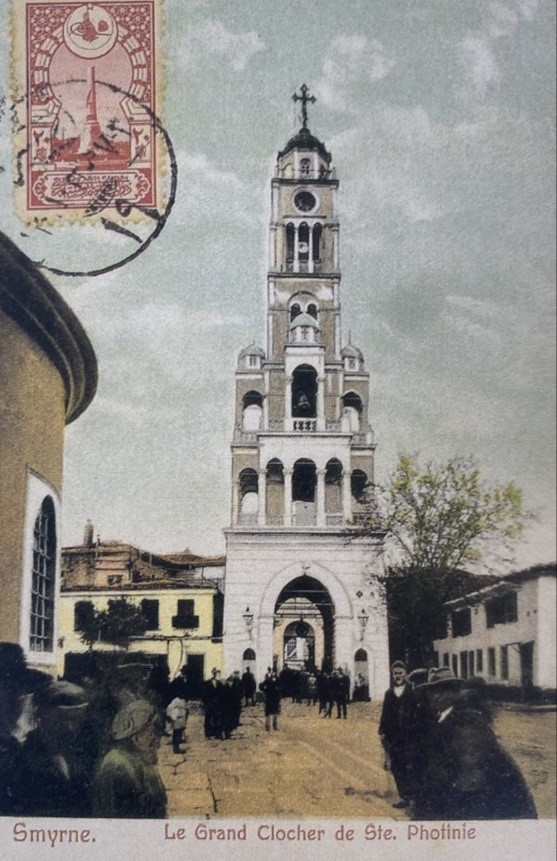

Panaghia Myrtidiotissa was the obvious religious marker for the Kytherians of Smyrna. The icon of the Most Holy Theotokos “of the Myrtle Tree” (found near Myrtidia on Kythera) was venerated in churches in a number of areas that had large Kytherian populations, including the town of Mersinli. It was also prominent in the Cathedral of Aghia Foteini in the centre of the city.

There are several accounts of when the Kytherians in Smyrna formed cultural associations.

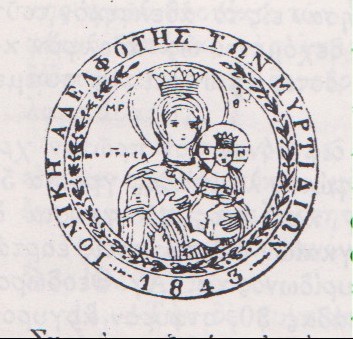

In around 1830 Kytherians established a brotherhood under the name “Kytherian Brotherhood, Panaghia Myrtidiotissa”, based on the inscriptions of the church of Aghia Fotini. The Ionian Brotherhood was formed in 1843 under the name of the Holy Theotokos of Myrtia. In 1886 the Kytherian Brotherhood Panagia Myrtidiotissa was established reflecting the continuing collective identity and religious association of Kytherians with the iconic symbol of the island. The Brotherhood was there to help members find work and to foster their cultural and social interactions as well as operate schools for the expatriates.

The main gathering points for the Tsirigosmyrniotes (the Cerigotes of Smyrna) were in fact the picturesque waterfront promenade filled with restaurants, wineries and cafes, the large taverns and the town of Mersinli near Bournova. [5]

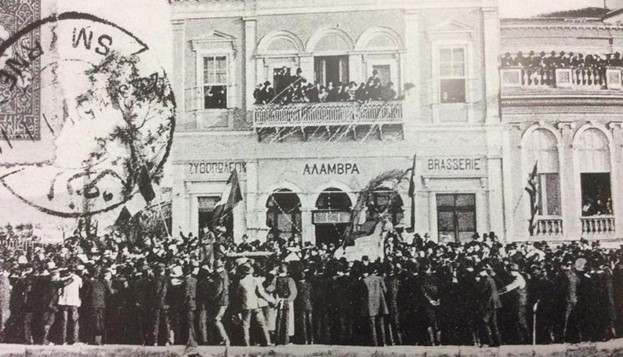

On the waterfront of cosmopolitan Smyrna, on the famous quay, was situated a beautiful, neoclassical building which housed the famous “Alambra”, one of the most important cafes of the Kytherian community. It was usually in front of the Alhambra that the diving for the cross on the Epiphany would take place as well as other important events. [6]

Another of the historic aristocratic cafes on the waterfront of Smyrna was the “Hermes” operated by Emmanuel Tzannes and which was frequented by artists of the lyric theatre. It was regarded as “the most Greek cafe on the waterfront”. [7]

But that era of contentment and tolerance came to an abrupt end in 1922.

On 9 September 1922, after the Greek armies in Asia Minor had been vanquished, the victorious Turkish cavalry rode into Smyrna. In the following days Smyrna literally became a hell on earth as it descended into chaos and barbarity. The city had begun to fill up with hundreds of thousands of Greek and Armenian refugees trying to flee the Turks. Within days Turkish soldiers and irregulars deliberately set the city ablaze after dousing the Armenian quarter with gasoline. Soon there were half a million people on the city’s quay, trapped between the harbour and the huge fire behind them.

But the Turkish barbarism did not stop there. The Greeks and Armenians in Smyrna were subjected to mass-murder, rape, looting, pillage and arson. The Greek Orthodox Bishop of Smyrna was hacked to death by a wild Turkish mob. Meanwhile, numerous British, French and other allied warships lay idle in the harbour, indifferent to the plight of the refugees, for fear of offending the Turks.

Desperate to escape the fire, refugees crowded the narrow waterfront, where they were penned in by Turkish soldiers and kept without food or water. Thousands were killed or died of hunger and disease. Many committed suicide by leaping into the sea. And the constant screams and moans and shrieks of the women and children stranded on the quay could still be heard.

Despite these grotesque scenes the Great Powers did not intervene on the pretext that they had to observe ‘neutrality’ even though the war had ended. The American Consul at the time, George Horton, later wrote a book “The Blight of Asia” in which he lamented the destruction of Smyrna and the horrors on the quayside and confessed to a “feeling of shame that I belonged to the human race”.

As a British newspaper reported, after the fire and horrors in the city apart from the squalid Turkish quarter Smyrna “has ceased to exist”. More than 100,000 souls perished.

The survivors were ultimately evacuated on Greek ships, largely through the efforts of Asa Jennings, an American working in Smyrna.

But the horrors were not confined just to the port as harrowing accounts began to emerge of Turkish atrocities in the surrounding towns and villages. One of the eyewitnesses was Panagiotis Marselos (himself of Kytherian descent) who gave this account of his attempts to escape the vengeful fury of the Turks:

“In the morning we left from Bournabasi. The Turks started to undress us, including my brother. When we reached a place between Bournova and Magnesia there was a fountain. We had gone three days without water. We stopped at the fountain and they ordered us to drink water. As soon as the people went to the fountain to drink the Turks pulled out their guns and starting shooting them in a line. Seeing this, I ran down towards the river and jumped into a pit which contained water but also a swollen and rotting corpse of a dead Greek. However I could not stand the thirst and I filled my hat with water which I took to my brother. He also drank and the fat from the broken corpse stuck to my lips.” [8]

Many simply vanished.

The photo above of Aroney School Orchestra was taken in 1922. In Noel Barber’s “Lords of the Golden Horn” the author recounts the events leading up to the fire which destroyed Smyrna and how people were consigned to a living death and commented that the Turkish belly dancers were in tears because the Greek jazz bands which supported their act had disappeared. I wonder what happened to the musicians in the group.

After the Catastrophe, less than five hundred returned to the island (with almost half aged 20 years and younger) and even then for a short time in many cases, with the largest concentrations in Potamos, Mylopotamos, Karvounades and Hora.

taken soon after the exchange of populations in 1923.

Many Smyrnioi-Kytherians (also known as Smyrnioitsirigotes) who managed to escape never went back to Kythera, or even visited the island. After the events of 1922, the majority of Smyrna’s Kytherian population – and in this respect they were not alone – settled in and around Piraeus with other refugees from Asia Minor and preferred to be known as Smyrniotes of Kytherian origin, thus choosing to be counted together with the other refugees of the “Asia Minor Catastrophe”. [9]

A few years ago I was fortunate to be able to visit present-day Izmir. Very little of the old city of Smyrna remains. As I walked along the historic quayside I stopped at a rather poignantly named café – the Nostalji Café – and had a chance to reflect.

I could not help but recall the words of the British writer Lawrence Durrell, that all the cruelty, injustice and madness of the Smyrna disaster continues to constitute a “sense of the lost richness, a lost piece of mind”.

We must never forget Smyrna and the Asia Minor Catastrophe of 1922.

Notes:

[1] I am indebted to G. Morton, Paradise Lost Smyrna 1922: The Destruction of Islam’s City of Tolerance (Hodder & Stoughton, London, 2008), a compelling read.

[2] Based on the presentation by Dr George Argyropoulos on the theme “Kytherian Emigrants in Asia Minor” at the Third International Kytheraismos Symposium held in Kythera in August 2008. See also E. Kyriazopoulos & N. Lourantos, “Kythera – Smyrna: The steamboat connection of two places in the 19th c. and their unknown dimensions” in T. Pylarinos and P. Tzavara (eds.), 10th International Conference of the Ionian Islands (Vol 1, Corfu, 30th April – 4th March 2014, pp. 249-263

[3] Nikolaos G. Fotinos “Memories and Stories from Smyrna”. (Union of Smyrna Publications. Athens 1986)

[4] I. Karachritos and M. Varlas, “Immigrants in Smyrna – Refugees in Greece: Subsequent Transformations of Identity among Kytherian Migrants” in M. Stassinopoulou and I. Zelepos (eds.), Griechische Kultur in Südosteuropa in der Neuzeit. Beiträge zum Symposium in memoriam Gunnar Hering (Vienna, 2008)

[5] K. Michalakaki, Kytherian Migration and Brotherhoods: Smyrna, Alexandria and Attica (Kytherian Society of Studies, Pireaus, 2013) at p. 47

[6] The last manager in cafe was the Kytherian, Ioannis Haros-Haridis. With the fire the Alhambra was completely destroyed and Haridis and his family returned to Kythira .

[7] Eleni Harou, “Κυθήριοι της Σμύρνης” (The Kytherians of Smyrna) https://www.eleniharou.gr/kythirioi-tis-smyrnis/

[8] K. Kasimati, “Smyrna: The Larger Kythera: the Kytherians in Ionia (18th to 20th centuries)” (Gutenberg, 2014) at p. 470.

[9] M. Warlas and I Karachristos, “Genealogical Memory and Local Identity among the Smyrnioi-Kytherians” 8th International Panionian Conference, Kythera, Vol. 3 (2006) at p.138