By Con Emmanuelle*

As many of you know, I have been working furiously over the last few years, recording and documenting some truly amazing stories of Cypriot migration. Many of these stories will now feature in my next book which I am designing right now and hope to self-publish in the coming months.

These stories of migration are truly humbling. I remain in awe of the gutsy determination and resilience of these early migrants and by their strength of character. With only blind faith and a desperate hope to guide them, they crossed the oceans in their thousands and sailed to the ends of the earth with barely a penny to their name.

Most of the Cypriots I have interviewed for my next book told me that they left Cyprus after the Second World War to seek a better life and a better future. Many left to find work and financial security to help their families back home. As one man put it. ‘Of course we are happy that we came to Australia. It was the first time in our lives that our stomachs were full. If life was good in Cyprus, we would have stayed.”

Many of the Cypriot migrants who I had interviewed over the years, told me that they always had intentions of returning to Cyprus. They had planned to stay and work for a few years and then return home to their loved ones. One of the main reasons they did not return home was because of the civil unrest that was brewing on the island during the mid-1950s.

Between 1947 and 1955, seven thousand Cypriots chose Australia as their new home. They paid over 120 pounds for their ship fare with most going into debt to secure the funds. By comparison, Maltese migrants who were also British subjects, paid only ten pounds. Moreover, many Maltese migrants had the advantage of speaking English upon their arrival and having a lot more disposable income. It’s an interesting comparison don’t you think?

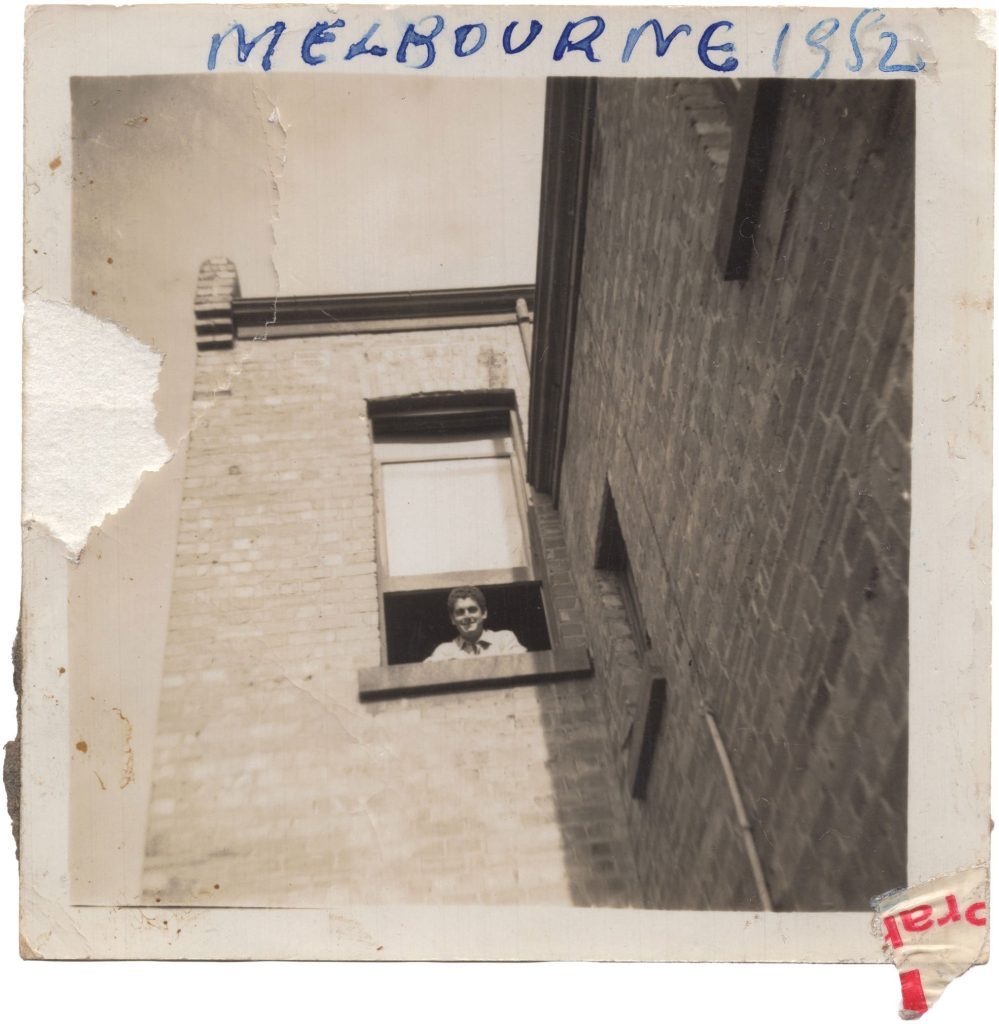

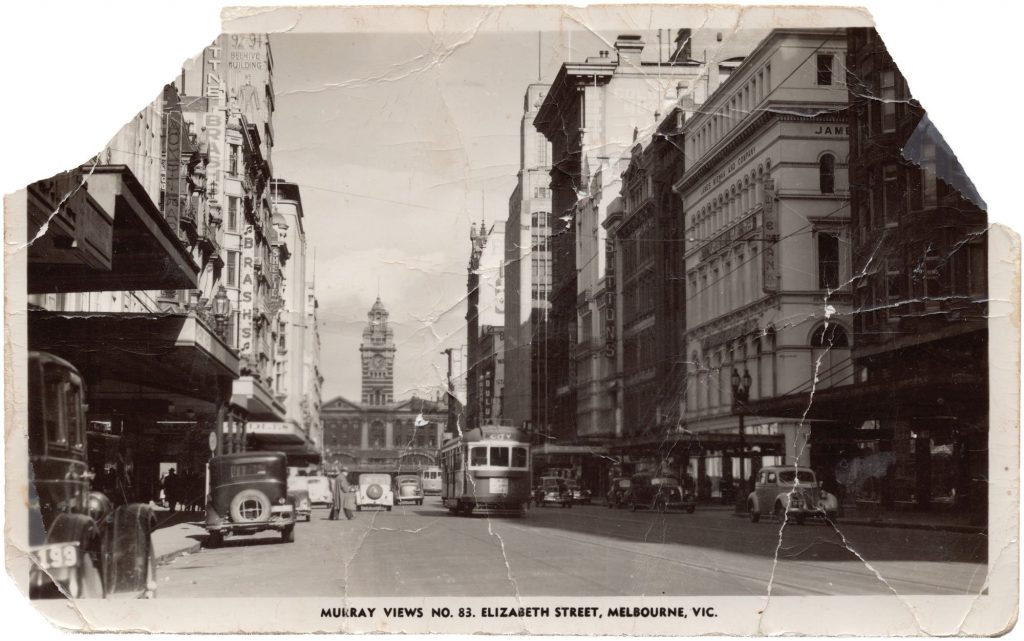

I feel so proud of my Cypriot heritage especially after hearing stories of the incredible comradeship and philoxenia of this remarkable generation of Cypriots. In my hometown of Melbourne, it was common in the 1950s for early migrants to go down to Station Pier to greet and welcome the ‘new’ arrivals from Cyprus. They would ensure they had a place to stay and even helped them to secure a job. How amazing is that!

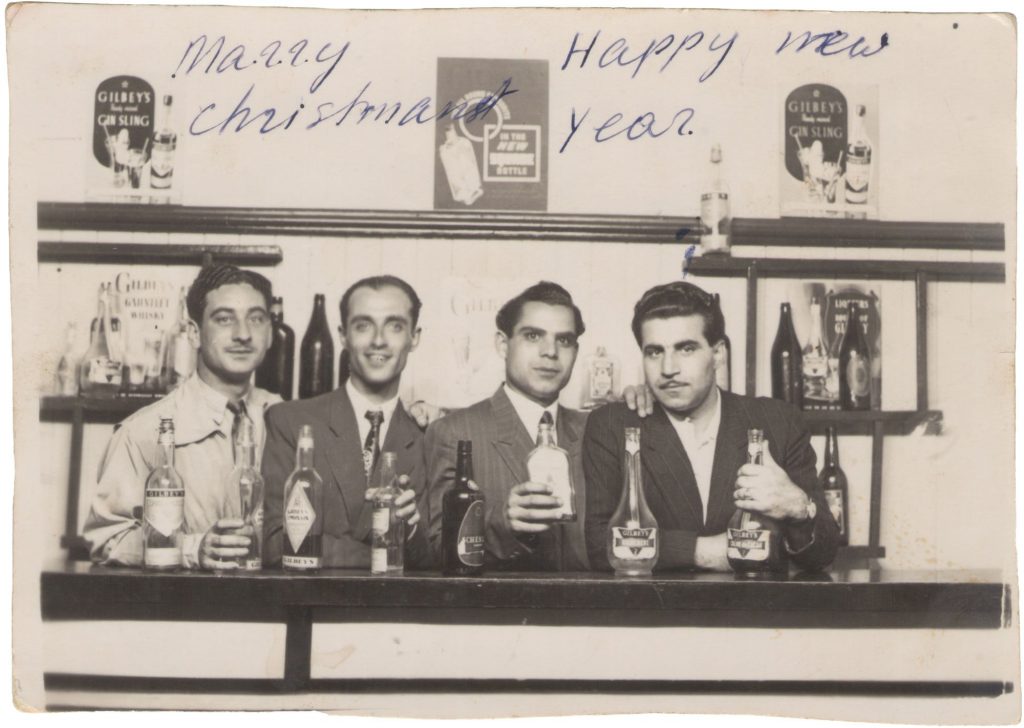

New Australians like my father would congregate with other Cypriot migrants at Greek cafes and clubs such as the Acropoli and Democritus sharing stories, eating familiar food and debating politics.

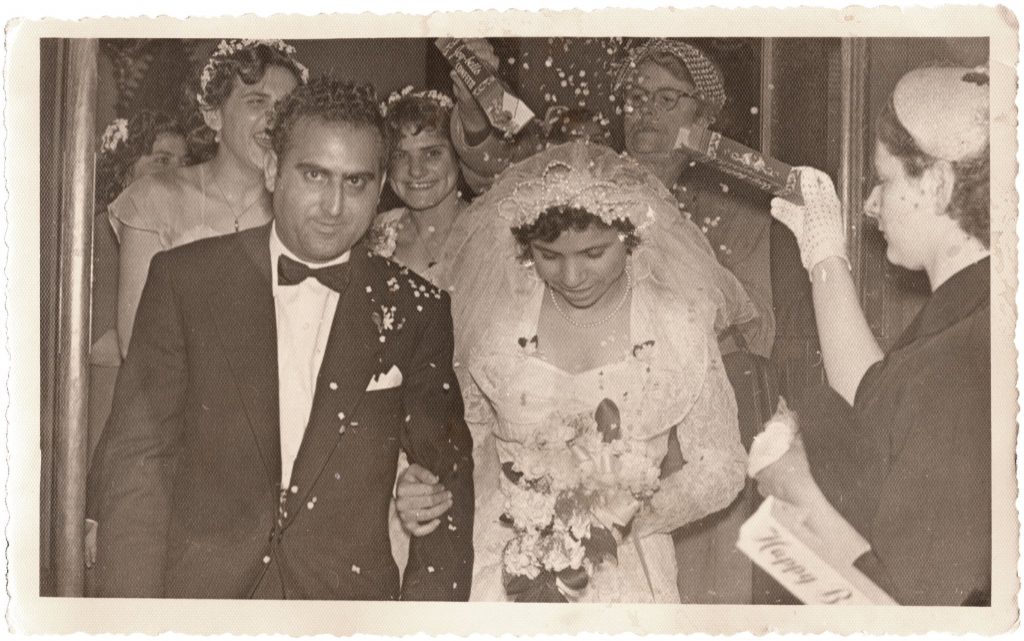

When it was time to settle down and get married, my father would choose a woman from his homeland. Since there were very few Cypriot women in Australia at that time, most men requested a bride to be sent over by ship. Such was the case and the fate of my dear mother.

These mail-order brides (as they came to be known) were sometimes forced to marry complete strangers, since it was their parents who would often arrange the marriage.

When I was born, my parents sold their cottage in Collingwood and bought a brand new brick-veneer house in the outer suburb of Reservoir (or Resa, as it is affectionally known by the locals). By the time I turned three, my father had converted the front and back yard into a vegetable paradise. He also planted and cultivated a small orchard of fruit trees as well as a pretty impressive grapevine. The chicken coop was at the back of the block. The only thing missing was a donkey and some goats. Needless to say, we enjoyed year-round fresh produce from the garden and ate fresh eggs almost every day.

My mother was also busy converting the interior of our house into a makeshift shrine and memorial to Cyprus. There were handmade embroideries and dollies in every room and countless religious icons and Cypriot keepsakes on every wall. I remember we had a giant map of Cyprus and a framed photo of Archbishop Makarios in our kitchen.

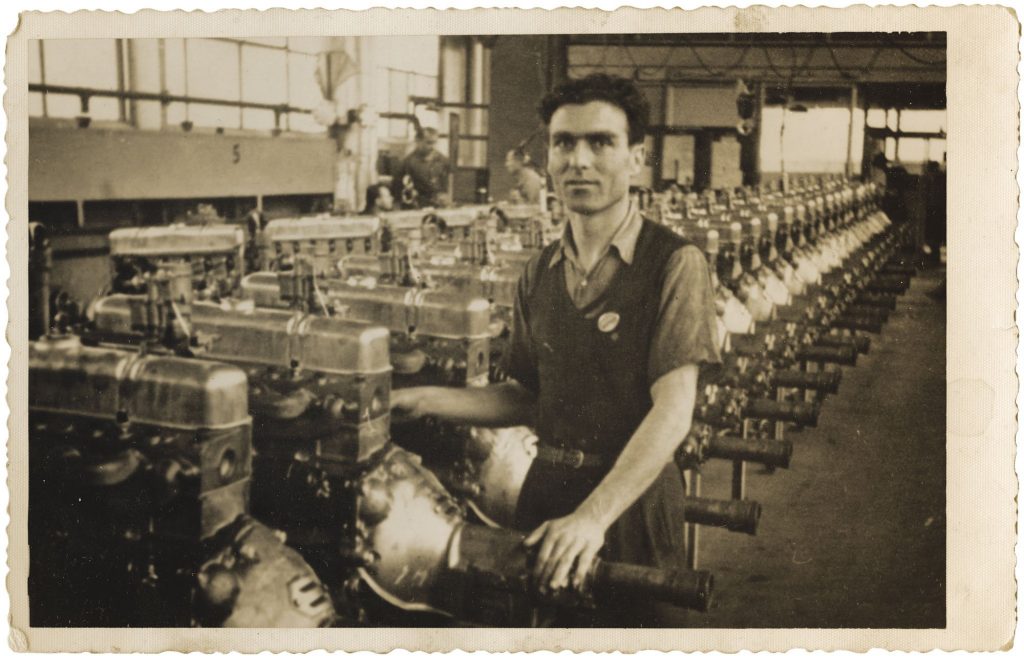

In the first few months or years after their arrival, many Cypriot migrants worked in factories or on farms or in the bush. Quite a few went on to become successful business owners, operating cafes, milk bars, fish and chip shops or becoming professional barbers, tailors and dress-makers.

Some migrants went to night school to learn English, others taught themselves or picked up a smattering of words and phrases on the job, so to speak. On Sundays, they would visit each other’s homes or pack a continental picnic and head out to a park or the countryside or any number of the magnificent Australian beaches. Yes, the shops were all closed on a Sunday in those days. Once there, men would get busy cooking the ‘souvla’ or sit together playing cards or ‘tavli’ (backgammon) drinking bottles of VB (local beer) while the women would prepare the Cypriot feast.

My father worked as a labourer in a factory for most of his life in Australia. He earned enough money to pay off his house and provide for his family. He did okay considering he arrived in Australia with no primary school education, no knowledge of English and only two pounds in his pocket. Other migrants did better. In fact, those who had the foresight to buy properties in the 1950s were able to then sell them a few decades later for 100 times their initial value.

It wasn’t an easy transition for those post-war migrants. The credit squeeze in the early 1950s created a lot of unemployment. The so-called lucky country wasn’t so lucky for many new arrivals. They found it difficult to secure a job.

Then there was the subtle but ever-present racism. Some of the locals treated the migrants as ‘aliens’ or undesirables. Even my generation, despite being born in Australia were also referred to as ‘wogs’.

I remember one hot summer night in 1972, a bunch of skinhead Aussie males (known as Sharpies) ripped down our front fence whilst shouting obscenities about my family. The phrase ‘go home you wog bastards’ was uttered more than once. My father could do nothing but look out at the destruction through the screen mesh of our front door. Thankfully, these incidents were isolated and few and far between.

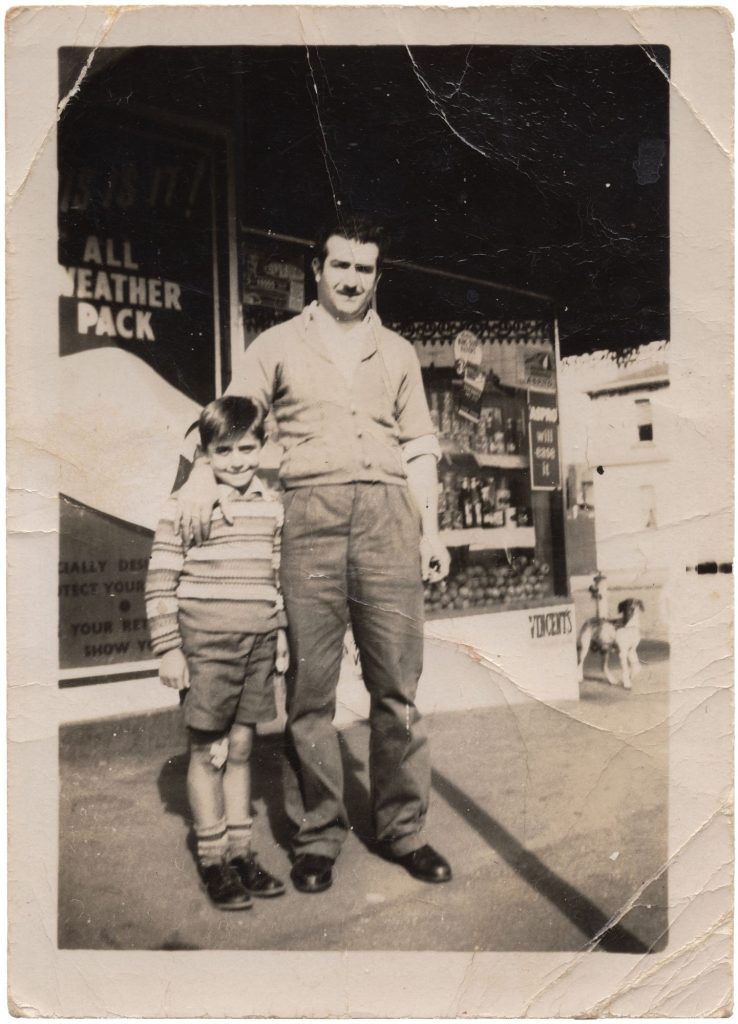

My father always kept a low profile and tried to stay out of trouble. He was always pleasant with the local Aussies and tried to assimilate with their culture and way of life whenever he was amongst them. At home however, he was a Cypriot, (as we all were) and fiercely proud of it.

My parents always taught me (and my siblings) to love and respect our traditions and customs. The only grief I would receive from my father was when I would visit the Hibberts, our next-door neighbours. He would yell and complain, often embarrassing me in front of them, simply because they were Australian. I guess in hindsight, he was afraid that they might convert me to their way of thinking or perhaps he was afraid I might lose my religion or cultural identity or run away with Carol Hibbert, who was a young teenager blonde girl. Mrs Hibbert was always nice to me. She would always offer me some biscuits or a bowl of tomato soup or a meat pie with sauce. Then I would go home and eat moujendra or tava. I was living a double-life.

Later as a teenager, my dress code became a source of great misery for my parents, especially my mother. She would rock back and forth whilst slapping her forehead with open palms lamenting the corruption of the youth in Australia. ‘Kyrie Eleison, Kyrie Eleison’, (Lord have mercy), she would cry and make the sign of the cross when she saw me getting dressed to go out.

Despite a bit of racism, I had a wonderful childhood growing up in Australia. In many ways, I took for granted the sacrifices that my parents made to ensure that my sisters and I had a better life – or at least, a better life than the one that they had endured. My father always reminded me that life in Cyprus was once quite harsh and cruel and that many people in his village suffered due to poverty. He was glad for the freedoms and opportunities that Australia could afford his family and proud that we were able to get a decent education and live a more prosperous life.

The Cypriot diaspora in Australia have been successful in maintaining and upholding their culture while at the same time assimilating into the Australian way of life. It has been a wonderful experiment that has enriched this great nation and proved that people from various backgrounds and beliefs can live together without malice or discrimination. Today, the local Aussies mix freely with the peoples from a hundred lands without prejudice or fear.

Thanks to my parents, I was raised to love both Australia and Cyprus equally. Think about it! One day I would be driving my V8 Holden Commodore to meet my Aussie mates at the pub and the next day and I would be eating the best Cypriot ‘souvla’ at my Uncle Andrew’s house whilst listening to Violaris on his turntable. It was the best of both worlds I guess.

Thanks to my migrant parents, I have had a good education that has allowed me to pursue the career of my dreams. I went from being a timid little boy sitting in the schoolyard with my homemade Halloumi sandwich to becoming a confident and successful graphic designer sipping hot, skinny cappuccinos with the cool kids on Chapel Street in Prahran. Not a bad transition. My career was allowed to blossom because of the love and support of my parents. In other words, I was only able to do the things I wanted to do because they were able to prop me up and propel my forward.

Thanks to my parents I speak two languages. This gift has enabled me to communicate and interview Cypriots for my Tales of Cyprus project. Thanks to my parents I have learned the value of caring for others and becoming a sensitive and caring parent myself. Thanks to them, I view the world with optimism and have gained an enormous respect for my cultural heritage.

Yes, I owe my migrant parents a world of gratitude for they sacrificed so much to pave the way so I can have a better life and future.

Thank you mum and dad. You are, and always will be – my heroes.

*Con Emmanuelle’s second book titled ‘The Corsica: Amazing Stories of Cypriot Migration’, is due to be released at the end of this year. For updates and information follow his Facebook page Tales of Cyprus.