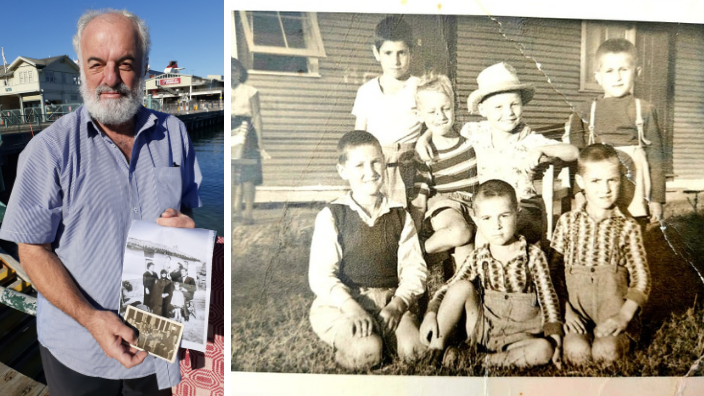

“We weren’t expecting anything flash. We were just coming out for a better life,” Angelos Zissis, 71, tells The Greek Herald as we sit down for our exclusive chat.

‘Nothing flash’ is exactly what Angelos and his family were faced with when they first migrated to Australia from Greece in 1954 and ended up at the Bonegilla Migrant Reception and Training Centre.

Bonegilla was the official employment office through which about 15,000 assisted Greek migrants were processed in what was called ‘the ICEM Greek Project’ between 1953 and 1956.

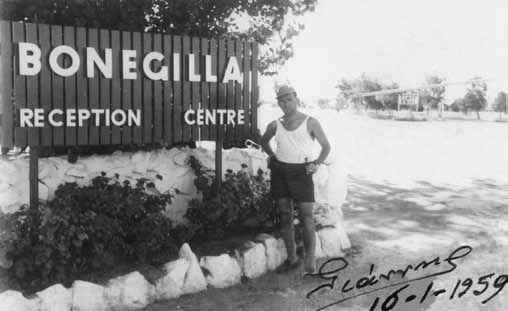

Greek migrant next to the Bonegilla sign. Photos by Vogiazopoulos.

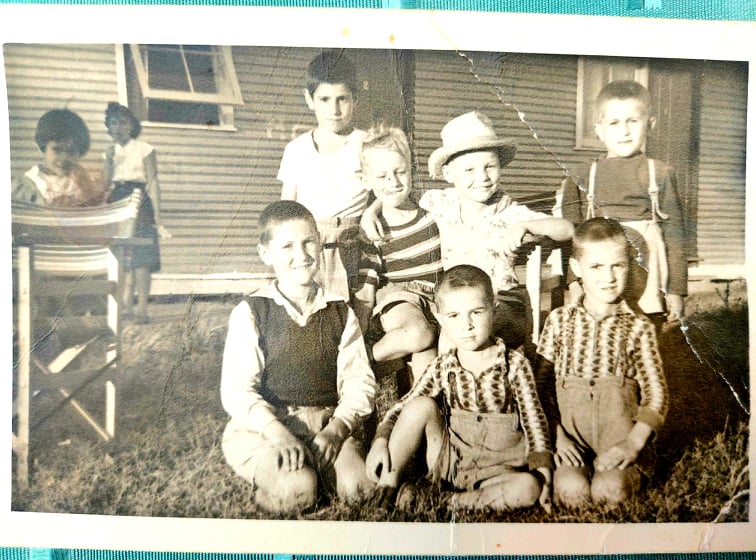

Greek dancing at Bonegilla.

On arrival at the centre, Greek migrants were allocated a hut and issued with eating utensils, crockery, towels and bedding. The living conditions were very basic and as Angelos remembers, it definitely wasn’t a five-star resort.

“It was like an army camp,” Angelos, who was five years old at the time, says.

“But obviously all the Greeks stuck together because they could speak the language.”

Of course, newcomers could choose to attend language classes where they were taught survival English and something about Australian ways, including weights and measures, hygiene standards, history and geography.

But still many Greeks weren’t able to get used to other aspects of the camp, such as the British-style meals which were served in the cafeteria.

“Coming from a Greek background, the Greek cuisine was very different… so [the food] was pretty tasteless to them initially,” Angelos explains.

Julia Fragopoulos, who’s dad stayed in Bonegilla when he migrated to Australia with his family in 1957, couldn’t agree more.

She shares how her dad’s mum was so ‘fed up’ with the ‘bland food’ at Bonegilla that she took matters into her own hands.

“My grandma went picking for radikia (dandelion greens) in the field and then went to the local chemist to buy some oil to cook them,” Julia says with a little laugh.

Others, such as Lambis Englezos who migrated to Australia in 1954, saw Greek migrants ‘catch rabbits’ at a nearby lake and cook those for dinner.

Ultimately however, many didn’t have to suffer the unsavoury food for long as Bonegilla was an in-between place, a transition zone.

Within a number of weeks, Greek migrants usually left Bonegilla to undertake two years of labour of the Australian government’s choice.

Many ended up working on construction sites and with the railway in remote areas, before they were free to make their own way in the country.

Many never looked back.

“We didn’t leave Greece with my grandmother’s blessing, but my father told me he never regretted the decision to come out to Australia. It was very difficult making the change but he didn’t regret it,” Lambis concludes.

A sentiment echoed by many who passed through the gates of Bonegilla and moved onto a better life Down Under.