By George Vardas.

The recent tour of Australia by the acclaimed Greek singer, Dimitris Basis, was especially significant because audiences around the country had an opportunity to experience one of Mikis Theodorakis’ great works, the Ballad of the Dead Brother (Το Τραγούδι του νεκρού αδελφού).

The concert in Sydney, held under the auspices of the Greek Festival of Sydney, was sold out as Basis, one of the late composer’s favourite singers, together with a superb local orchestra conducted by George Ellis, brought the ballad to life.

READ MORE: Dimitris Basis: ‘Here in Australia there is a piece of Greece’.

Whilst perhaps not as well-known as other popular compositions, such as those grounded in the stirring poetry of Yannis Ritsos or George Seferis, the Ballad of the Dead Brother is epic theatre with lyrics and music written by Theodorakis.

It is true folk tragedy based on lived experiences during the brutal Greek Civil War that broke out at the end of World War II and raged in Greece until 1949. Theodorakis had lost friends in the civil war on both sides and through his Ballad these lost souls finally get to speak.

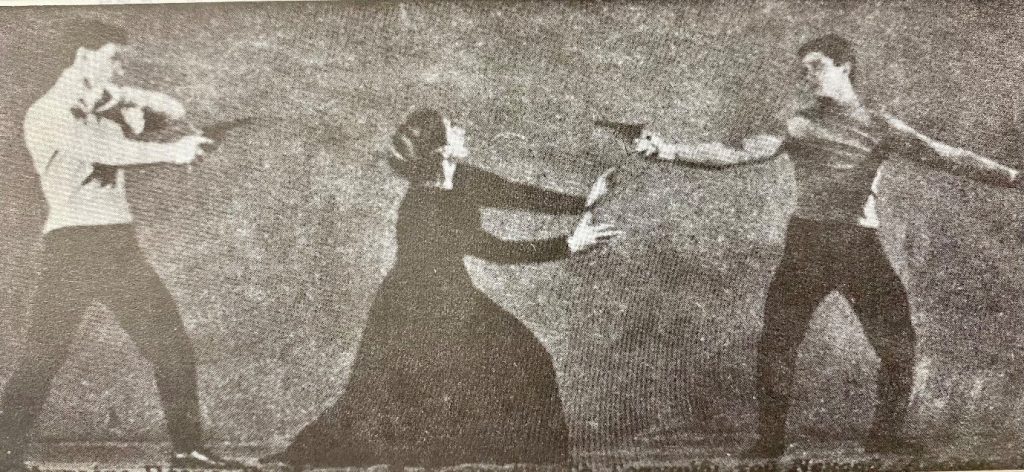

Pavlos Papamercouriou was a student who Mikis knew well and who joined the resistance and the anti-government forces. The composer then devised in his imagination a brother, Andreas, who was a rightist and fought in the ranks of the National Army. Pavlos, aged just 25, was executed in 1949 after inhuman torture by the regime. Andreas died in the fighting.

Between them stands their distraught Mother who unsuccessfully tries to reconcile them.

At the epic level, the two brothers represent the warring Greek factions whilst the anguished mother is Greece who is destroyed by their hatred. The mother’s love is the main element of tragedy. According to Theodorakis, “the mother in the laik songs is the most sacred, the sweetest, the most priceless theme of the melodist”.

In the prologue, the chorus is the orchestra. Upon its entrance after the first song, “April”, which sets a false mood of festivity, the chorus engages the audience directly through the song “The Dream” which gives the essence of the drama:

You had two sons, my mother,

two trees and two rivers

two Venetian castles

two springs of jasmine, two worries.

One goes to the east

on the other goes to the west

a new, standing in the middle,

speak and ask the son

if you ever see Pavlos, call me

and if you see Andreas, tell me

I raised them with the same anguish

and with the same sob I bore them.

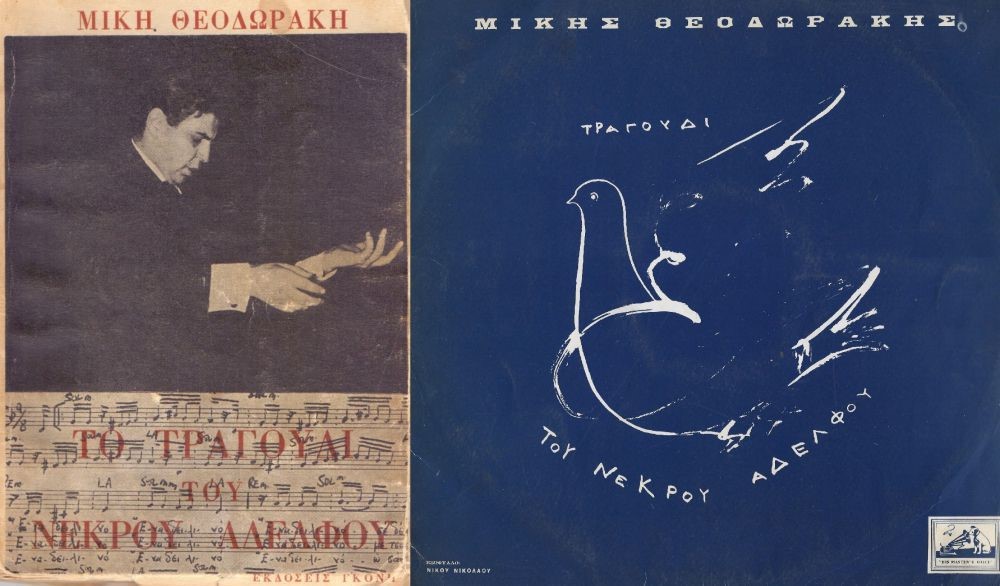

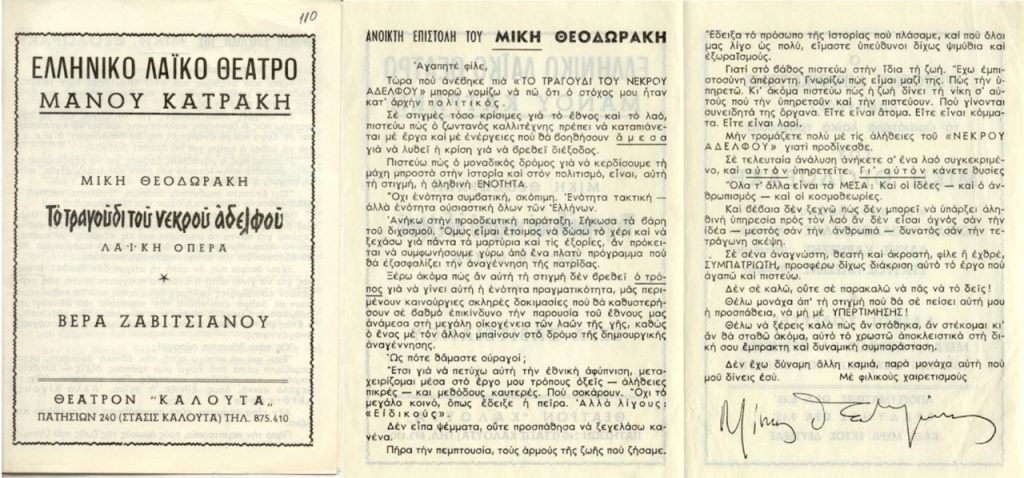

First performed in 1962, it sparked controversy. Theodorakis actually penned an open letter to the audience on the opening night of the performance in November 1962 at the Greek Popular Theatre of Manos Katraki.

The letter read in part:

Dear friend,

Now that “THE SONG OF THE DEAD BROTHER” is up, I can say that my goal was primarily political.

At such critical moments for the nation and the people, I believe that the living artist must embark on works and actions that will immediately help to resolve the crisis in order to find a way out. I believe that the only way to win the battle against history and culture is, right now, the true UNITY … essential unity of all Greeks.

I belong to the progressive faction. I lifted the weights of division. But I am ready to lend a hand and forget forever, the tortures and the exiles, if we are to agree on a broad program that will ensure the rebirth of the homeland.

So in order to achieve this national awakening, I use in my work bitter truths. I did not lie, nor did I try to deceive anyone. Do not be too frightened by the truths of the “DEAD BROTHER” because you are betrayed.

At the time, Theodorakis was dismayed that the song cycle of the Ballad of the Dead Brother was criticised on both sides of politics although he was quick to dismiss it as “contemptuous criticism” and “blind hatred”.

The folk drama was in fact partially censored by the Rightist Government which believed the Civil War was an unmentionable crime perpetrated by communists and therefore resented the very notion of national reconciliation which, in their eyes, effectively shared responsibility for the civil war and its excesses between the ‘perpetrators’ and the ‘victims’.

The Left ignored the work because they objected to the thought of holding hands with fascists who had previously aimed their guns at their fellow Greeks.

One of the original songs, “Chain”, recounted how yesterday’s friends and today’s enemies remember together scenes from the Occupation in which the Greeks were united – like a chain – in fighting against the foreign invaders:

I turn the heavy chain into a swallow

I turn the dark prison into clear sky

The heavy chain

Me and you and you and you and you

Together we will cut it together

The final song – “Unite” – signals the denouncement, thereby symbolising the complete circle of life and death. All those who have been killed in the Civil War – rightists, leftists, policemen, revolutionaries – march forward towards the audience holding hands.

Unite stone and stone

Unite hand in hand

The mountains and the ravines begin the song.

Cities and harbours join in the dance:

Today we marry the sun

The sun to the bride, the dearest, the Joy!

Mikis Theodorakis would later write that he identified more with Ballad of the Dead Brother than any of his other works in every respect: music, human, experiential, competitive and above all Greek since the civil war had plunged Greece into tears, in blood and in an endless test.

Behind the melody and the music are the stirring lyrics born out of the bloody civil war, expressing at once the frustration of the internecine struggle and the fervent hope that Greece will rise reunited. Epic tragedy and drama that are both haunting and uplifting as brotherly love ultimately prevails over hatred.

Mikis Theodorakis first met Dimitri Basis in 1999 when the young singer was performing in a concert to honour the great composer on the island of Samos. As relayed by Greek Herald journalist Andriana Simos who interviewed the singer during his recent visit to Australia, Theodorakis went up to congratulate Basis on his singing and then paid him the ultimate compliment: “You have a great traditional Greek folk singer’s voice and you would be perfect to sing Το τραγούδι του Νεκρού Αδελφού”

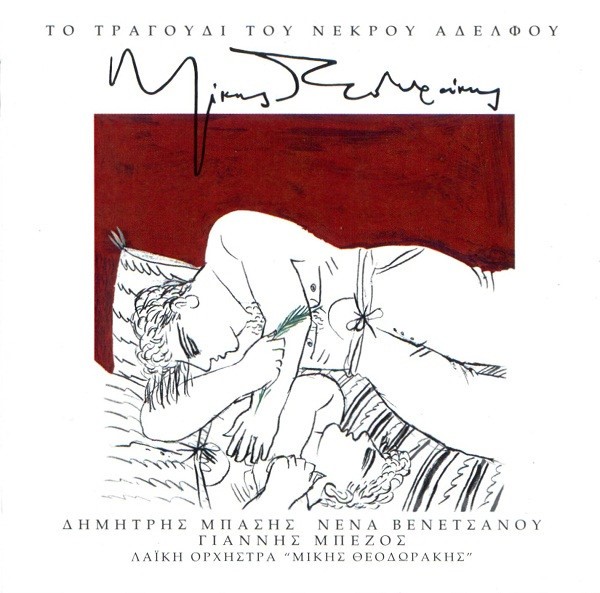

In 2001, Basis was given the opportunity to do a fresh interpretation of the ballad and to include some songs that were initially banned.

The great composer reassured him that he would succeed and not to think about the first rendition of the ballad by the great popular (laik) singer Grigoris Bithikotsis. Theodorakis told Basis: “Don’t think about it. Let yourself go and I will retrieve from your soul what I can”.

More than two decades later Australian audiences heard that same distinctive voice which impressed Mikis Theodorakis and were treated to a wonderful rendition of this most impressive of Theodorakis’ ballads.