The Greek national and nationalist consciousness regarding Cyprus was expressed in various forms and underwent several phases in its evolutionary course.

Given the just historical, cultural, and demographic presence of Greek identity in Cyprus and the patriotism of the Greek Cypriots, the national vision was initially expressed as an anti-colonial struggle against the British colonisers (1931), which later gradually developed into an ideology with the main goal of emancipation, union, and integration of Cyprus with Greece.

The typology of nationalism and irredentism in Cyprus was interpreted based on the ideological approach of its citizens—sometimes as a desired ideal, historically and nationally substantiated with Hellenism, and at other times as a result of pressures exerted by the colonisers and Western interests in Cyprus in order to maintain their sovereign rights on the island.

There were various proposals for resolving the Cypriot tragedy with different intensities and degrees of claims, with different protagonists oscillating between a pendulum of maximalist interests concerning gaining more, and minimalist ones concerning offering less.

In general, Hellenism failed to identify the right balance that could lead to a compromise solution to the intercommunal problem, thereby giving Turkey, for the second time in our days after 1974, the opportunity to shift what was purely an intercommunal issue of a unified and, at most, federal Cyprus into a problem of interstate partition, strategically and systematically pursuing, clearly, the illegal annexation of the territories of a partitioned northern Cyprus.

Let us now turn our attention to the Annan Plan. Beginning in the 1950s, the Greeks by race, origin, and culture in Cyprus were divided into two ideologies: those centred on Greece, declaring Enosis with Greece and rejecting as illegal and unpatriotic any other solution; and those who believed in and professed an independent Republic, where the two ethnic communities could determine their fate without the military presence of a third power.

During the numerous international rounds of negotiations, discussions, and consultations under the auspices of the UN, which led to the 2004 referenda regarding the Annan Plan and the rise of Turkish neo-Ottoman nationalism that prevailed in the years that followed—particularly after the discovery of natural resources in Cyprus’ Exclusive Economic Zone—discontent between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots over the status and destiny of Cyprus continued to play a primary role in their relations.

The crisis faced by the Republic of Cyprus after the invasion reached its peak when the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kofi Atta Annan (1938–2018), supported by much of the international community, proposed the most coordinated and detailed plan for achieving a federal solution to the Cyprus problem.

There was strong support from the EU because Cyprus, represented internationally by the Greek Cypriots, was due to join the bloc of European countries in 2004. The EU wanted to see the island reunified first. There was also strong support from the US government and its president, George Bush. However, in a twin referendum on 24 April 2004, the Greek Cypriots, led by President Tassos Papadopoulos (1934–2008), overwhelmingly rejected (75.8%) the Annan Plan, while the Turkish Cypriots, contrary to the will of their leader, the militant nationalist Rauf Denktash, accepted it (64.9%).

Annan presented a first version of his plan in November 2002 and a fifth and final version in March 2004. He wanted the final text to emerge from negotiations between the two sides, but amid ongoing deadlock, he finalised the text himself. The overwhelming majority of Turkish Cypriots appeared enthusiastic, hoping that a settlement would allow them to end their isolation by joining the EU along with the Greek Cypriots in a reunified Cyprus.

Greece, in general, also supported the Annan Plan, as did Turkey, where the Justice and Development Party (AKP) had won a sweeping victory in November 2002 under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

There were fewer incentives for the Greek Cypriots, who had already secured EU accession by April 2003. President Papadopoulos strongly opposed the Annan Plan and, in an emotional televised speech, urged Greek Cypriots to reject it. He argued it was tailored to suit Turkish interests at the expense of Greek Cypriot rights and would legitimise the de facto partition of the island rather than reunite it. Papadopoulos also miscalculated that the Greek Cypriots could secure a more favourable settlement of the Cyprus problem once they joined the EU.

His speech prompted the communist party, AKEL—then a coalition partner in his government—to withdraw its previous support for the UN proposals. The conservative Democratic Rally [DI.SY] party, led by Nicos Anastasiades, supported the Annan Plan, as did two former presidents, George Vassiliou and Glafcos Clerides.

Annan expressed his disappointment at the Greek Cypriot “no,” as did Washington, London, and Brussels. Cyprus entered the EU one week later (1 May 2004), with only Greek Cypriots enjoying the benefits of accession. The acquis Communautaire, or body of EU law, was suspended in northern Cyprus pending the island’s reunification.

How do we assess the current situation in 2025 based on the 2024 Annan Plan:

The Annan Plan proposed the establishment of the United Cyprus Republic, “an independent state in the form of an indissoluble partnership, with a federal government and two equal constituent states, the Greek Cypriot state and the Turkish Cypriot state.”

The structure of this bi-zonal, bi-communal federal democratic entity would be based on the Swiss model. The state would have a single international legal personality and single sovereignty. People would hold two citizenships: that of the common state and of the constituent state in which they lived. The latter would complement, not replace, Cypriot citizenship. Acquisition of Cypriot citizenship would fall under federal law, meaning the federation would control immigration.

Any unilateral change to the status quo established by the agreement would be prohibited—especially union of Cyprus in whole or part with any other country, or any form of partition or secession.

The federal government would be responsible for foreign policy and international relations, ensuring Cyprus “can speak and act with one voice internationally and in the European Union.” It would also be responsible for Cypriot citizenship and the issuance of passports, immigration, antiquities, and certain other matters. Powers of the constituent states would consist of everything not governed by the common state, meaning each would have a high degree of autonomy. They would cooperate through agreements and constitutional laws to ensure they do not violate each other’s powers and functions.

The new state of Cyprus would be governed by a federal parliament composed of two chambers. A Senate (upper house) would have forty-eight members with equal numbers from each community, while a Chamber of Deputies (lower house) would have forty-eight members, no fewer than twelve of whom would be Turkish Cypriots. Parliamentary decisions would require a simple majority in both chambers to pass. There would also be separate legislative bodies in the two member states.

Executive power would be vested in a presidential council with six voting members. Parliament could also choose to add certain non-voting members. At least one-third of the voting and non-voting members would be from each constituent state. No fewer than one-third of members from each category would be Turkish Cypriots.

The presidential council would be elected on a joint ticket by special majority in the Senate and approved by the majority in the Chamber of Deputies for a five-year term. The council would strive to reach decisions by consensus. If that were not possible, decisions would be taken by a simple majority of members, provided that it included at least one member from each constituent state. The council would elect one member from each state to alternate every twenty months as president and vice-president. The member from the more populous constituent state would serve as president first in each term. The Foreign Minister and the Minister for European Affairs would not come from the same state.

A Supreme Court would have equal numbers of judges from each constituent state and three non-Cypriot judges who would not be Greek, Turkish, or British. The court would resolve disputes between states or between the federal government and the states.

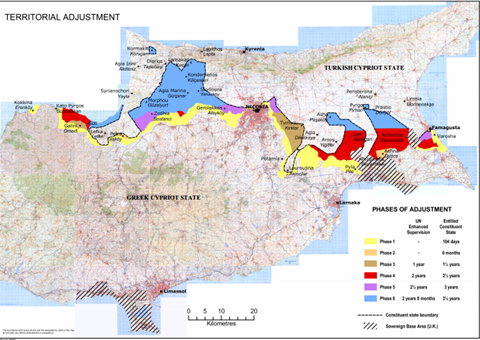

The plan proposed significant territorial adjustments in favour of the Greek Cypriots. Turkish Cypriots comprised 18% of the population at the time of the 1974 invasion but controlled 36.2% of the island’s territory. Their territorial share would be reduced to 28.5%, negotiable in harmony with the increased demographic burden resulting from tens of thousands of Anatolian Turks settling in the occupied territories. This would take place in six phases over a period of 42 months, beginning 104 days after the agreement came into force.

During the fifty-plus years following the Turkish invasion and occupation of Cyprus, successive Turkish governments designed and implemented a long-term demographic policy. Without overt party or ideological divisions, and following a permanent strategy of aligning the occupied territories proportionally with population, Turkey implemented a comprehensive settlement and socio-economic programme. As a result, by 2024, of the total 1,189,000 Cypriots, the population of free Cyprus stood at 889,000 and the occupied zone was estimated at nearly 295,000—around 26% of the total Cypriot population. Population density is 39 people per square kilometre in the free territories, but 93 per square kilometre in the occupied areas.

The execution of this strategy is widely attributed to Turkey’s populist leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and his autocratic regime. His long, stable, and rigid political tenure (1994–2024), initially as Mayor of Istanbul and later (from 2002) as Prime Minister and President, contributed significantly to the fulfilment of this goal.