In 2017, officials knocked on the doors of residents living on Randwick’s Eurimbla Avenue and told them their houses were to be compulsorily acquired to make way for a redevelopment of the nearby Prince of Wales Hospital.

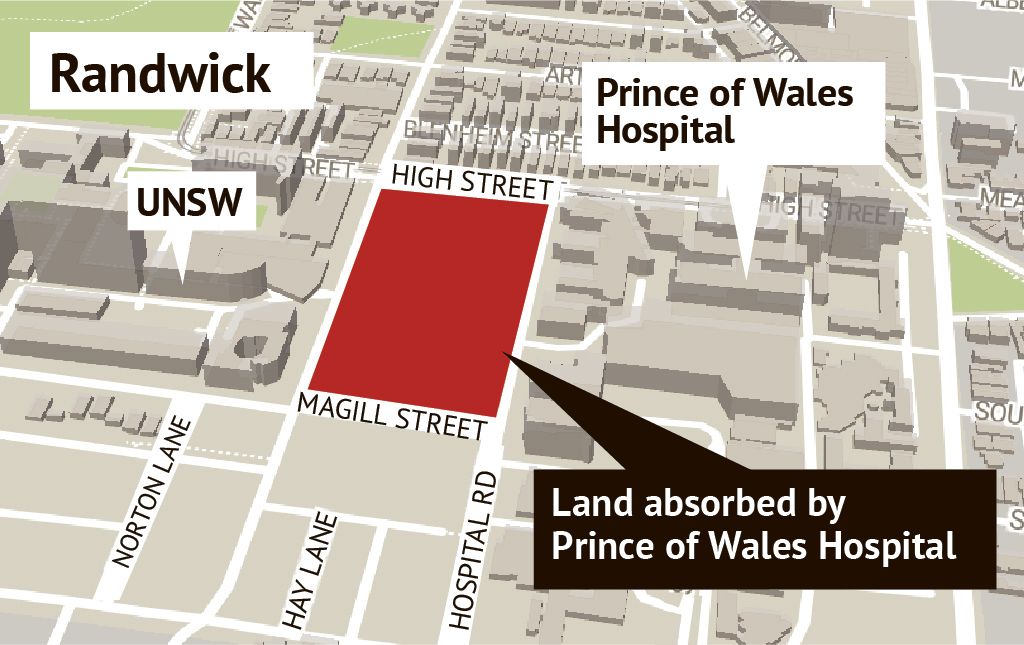

Residents were given a date and promised fair prices for their homes, but there was no negotiating about the fact they had to move out of the Eurimbla precinct, which is wedged between the University of New South Wales on one side and the hospital on the other.

Now, almost four years later, former Eurimbla resident, Sam Sarkis, tells The Sydney Morning Herald that while you could not pay him to move back to Randwick, he still missed his neighbours.

Mr Sarkis was one of the most outspoken critics of the compulsory acquisition process and has since moved to acreage on the Central Coast.

He tells the SMH the process (which was concluded by the end of 2018) was made unnecessarily stressful by the bureaucratic way it was managed, with many residents frantically renovating and painting their homes to get a higher valuation.

Mr Sarkis was told he could not take his new toilet with him. One man was told he could not take a magnolia tree that had been planted by his mother.

“They really dehumanised the whole thing… It could have been handled better,” Mr Sarkis told the Australian newspaper.

NSW Health Infrastructure said in a statement to the SMH that more than 90 per cent of property owners reached an agreement with the government on the value of their property without needing to resort to property acquisition and the process had been conducted in line with all its statutory obligations.

“Health Infrastructure understands the property acquisition process can be difficult for residents and owners and has made every effort to support positive outcomes on their behalf,” it said.

The Eurimbla Precinct History Association has now released a book, Remembering Eurimbla, funded by the garage sales of residents moving out of their homes and a grant from Randwick Council.

When Mr Sarkis opened the book, it was beyond anything he had imagined.

“The book gave recognition,” he said. “We weren’t just a number, which was how we had been treated [during the sell-off]. It recognised that we were people with stories, with families, with histories. That’s something.”

Source: SMH.