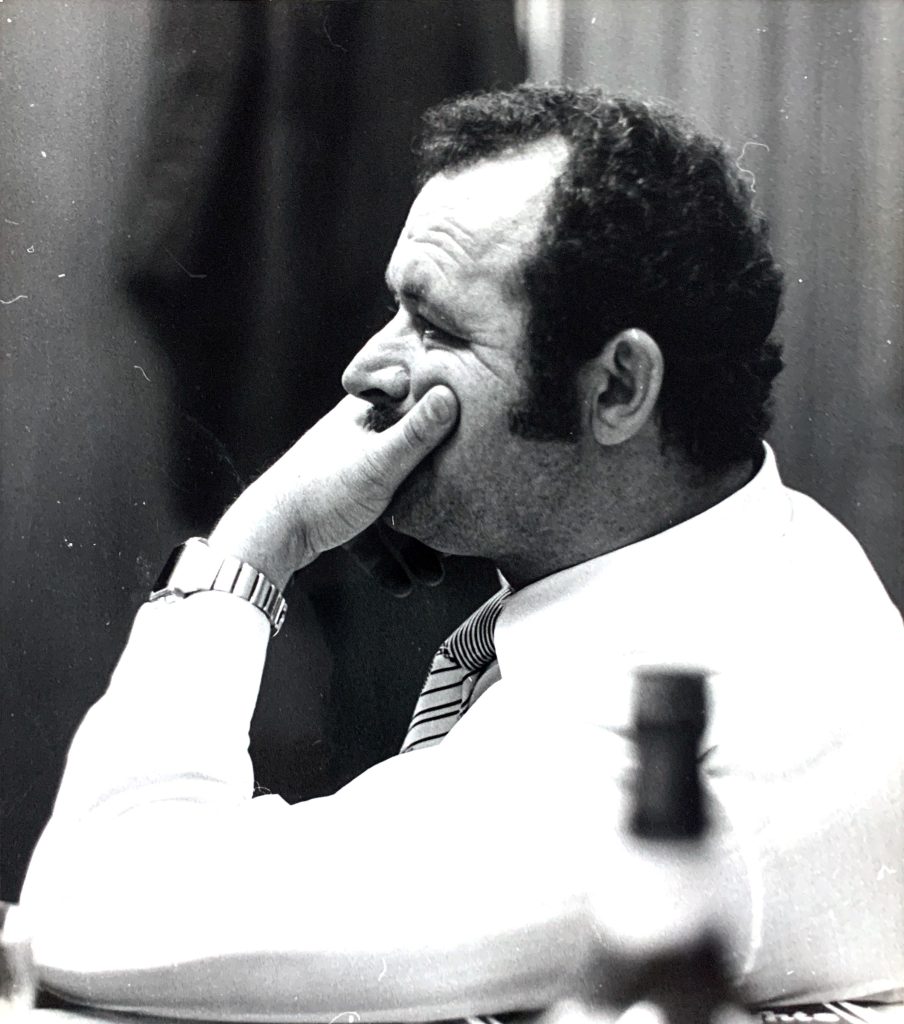

When the late publisher of The Greek Herald, Theodore Skalkos sat down for an interview with the National Library of Australia in March 2000, he was asked how he wanted to be remembered. After a brief pause, Mr Skalkos’ answer was simple.

“As I am…” he replied. “As Theodore Skalkos.”

Even five years after his death on 19 February 2019 at the age of 87, Mr Skalkos’ name remains synonymous with Australia’s ethnic media and the ground-breaking printing reforms he championed.

Political, community and sport leaders who knew Mr Skalkos also remember him fondly, whilst admitting he could be a controversial figure.

“He was part of Australia’s transition, often boisterous and argumentative but there to help,” former New South Wales Premier Bob Carr once wrote about Mr Skalkos. “Someone like Theo took risks and produced a successful business model. In the process he gained the respect and affection of many people across Australian leadership.”

Former Australian Ambassador to the United States, Arthur Sinodinos added, “Theo Skalkos was a larger-than-life character who lived life his way and never took a backward step. He could be the most generous of friends and the most unrelenting of adversaries.”

They weren’t wrong.

Skalkos’ entrepreneurial spirit:

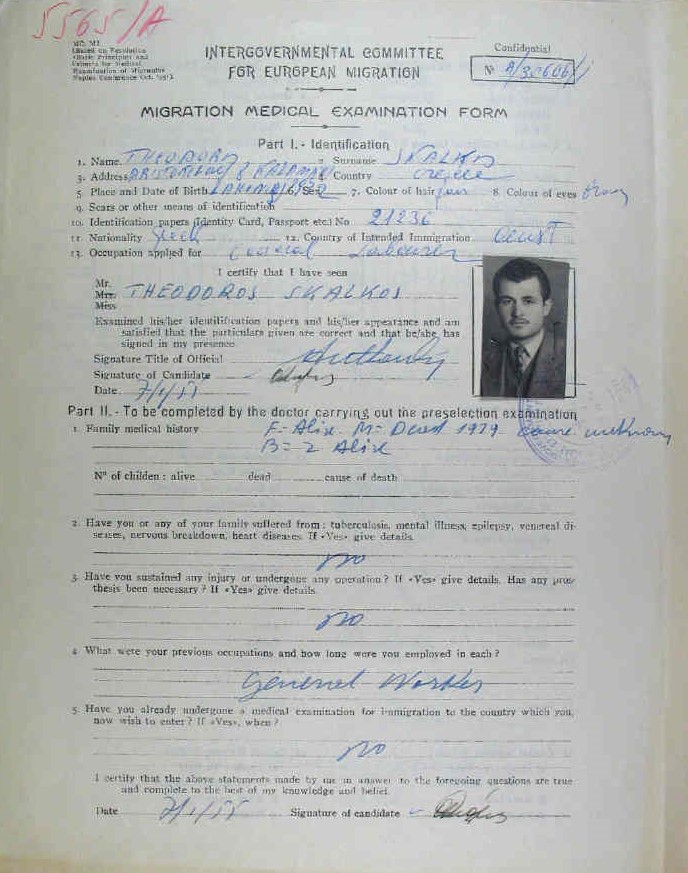

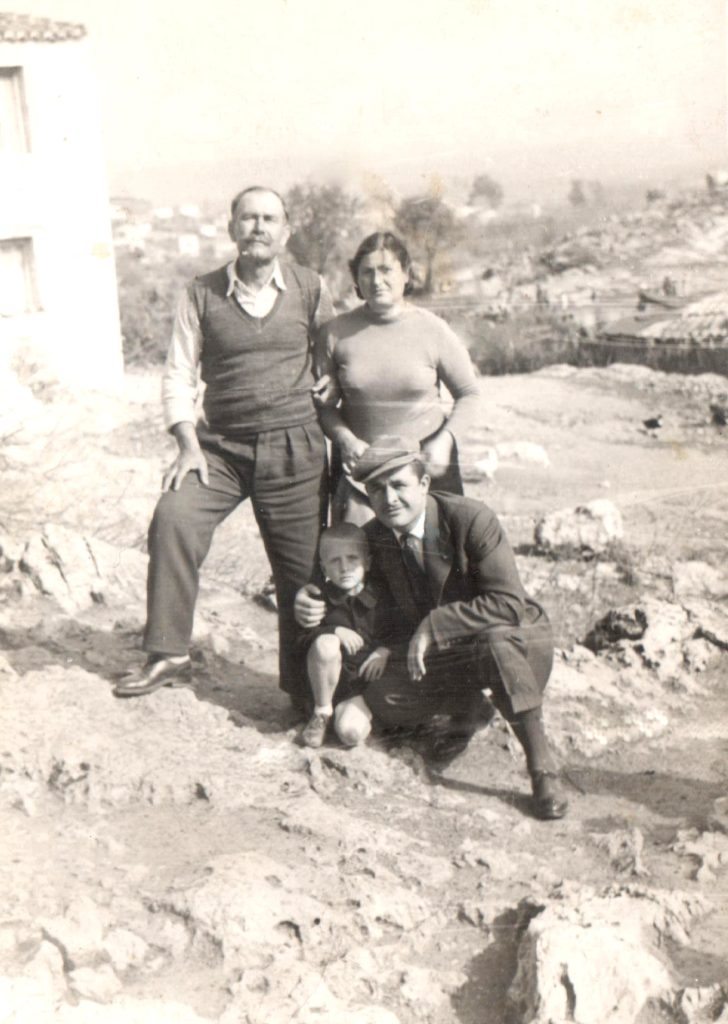

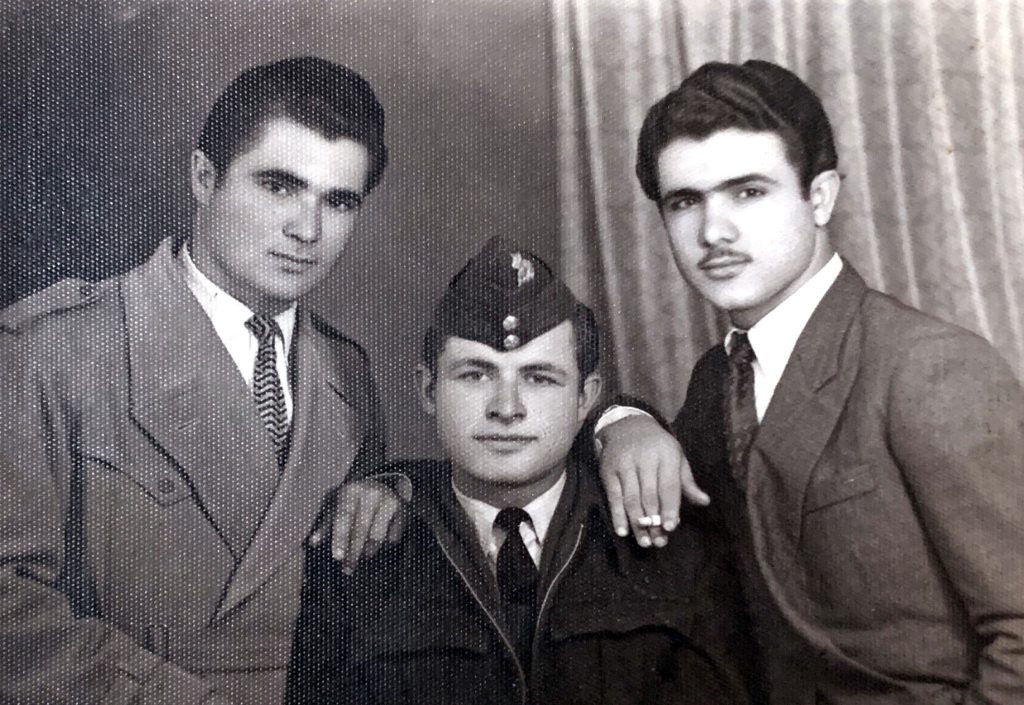

Born in Skala, Laconia, Greece on 2 February 1932, Mr Skalkos was always a hard worker, helping his dad on the family farm whilst trying to get an education and fulfilling responsibilities for his local church on Sundays. He finished high school in the Greek Air Force and left to join the Belgian airline, Sabena, which stationed him for a year in the Belgian Congo and then Australia.

He landed in Melbourne on 3 March 1955 and spent three months fixing machines at the Hilton’s stocking factory before he, along with five friends, went to work on a sugar cane farm in Queensland.

Eventually his five friends left the cane farm due to the demanding nature of the job and only Mr Skalkos and a Ukrainian man remained. When the season finished, the accumulated bonuses of all those who had come and gone went to Mr Skalkos and the Ukrainian. They split the money and ended up with 1,250 pounds each.

Later moving to Sydney, Mr Skalkos worked at Warragamba dam for three months and then at a vinyl veneer factory in Rosebery, which was located next to the Department of Transport.

During his interview with the National Library of Australia, Mr Skalkos described how an interaction he had at the factory led to his first business endeavour.

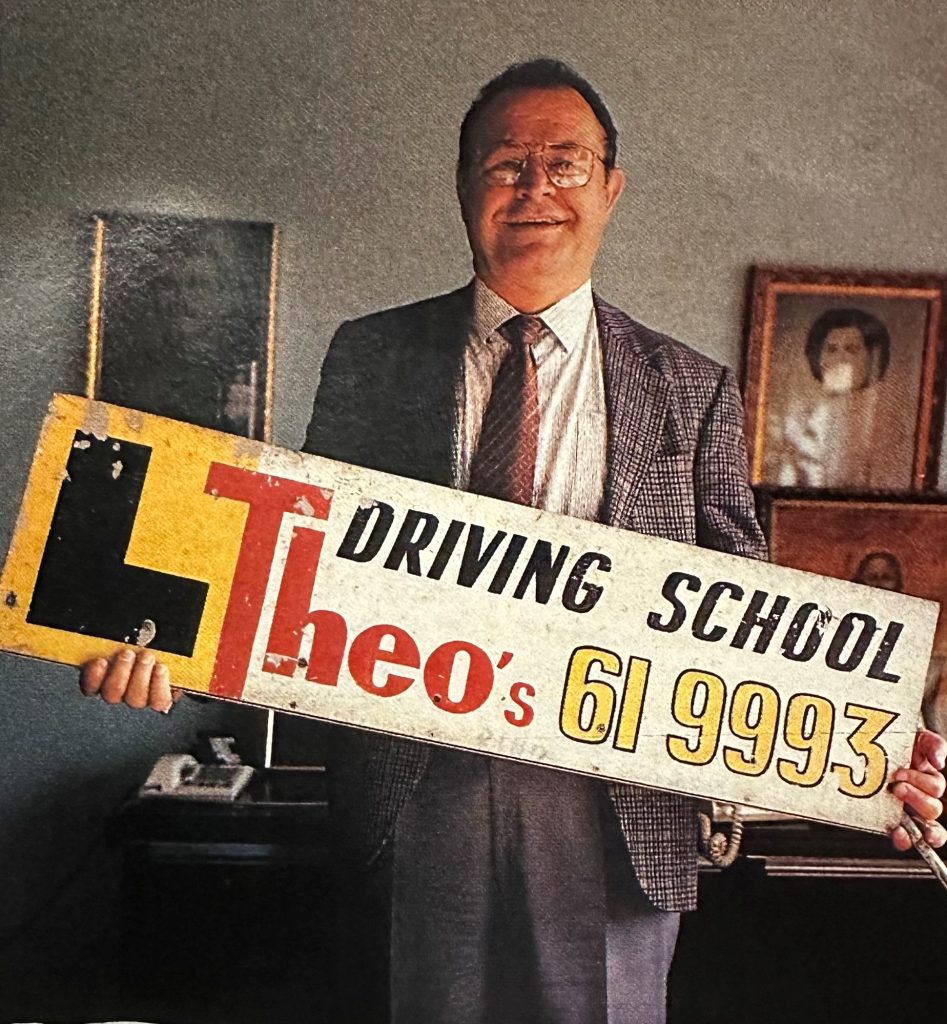

“During lunch one time, one of the driving examiners [from the Transport Department] said to me, ‘why don’t you buy a car to teach the silly Greeks to drive instead of working at the factory?’” Mr Skalkos explained.

The idea stuck and the next day, Mr Skalkos bought a ’52 Holden, added his own double braking clutch, and started the first Greek driving school in Australia in 1956. He called it ‘Theo’s Driving School’ and it grew to have up to 17 black Holdens. To maximise the use of the Holden fleet, he would lease them for weddings and christenings on weekends.

But Mr Skalkos didn’t stop there. His second business enterprise started soon after he visited another Greek who was running a sewing machine import business in Sydney.

“I was there to interpret for my cousin who wanted to buy a sewing machine. This old Yugoslavian woman comes in and she said, ‘will you teach me how to use the sewing machine so I can get a job in the factory? I will pay you.’ Three days later, I ordered sewing machines and started my sewing school in Castlereagh Street,” Mr Skalkos said.

Over 10 years, his sewing school taught 15,000 migrant women. Mr Skalkos said it was “the best business” he had.

Skalkos’ ethnic media empire:

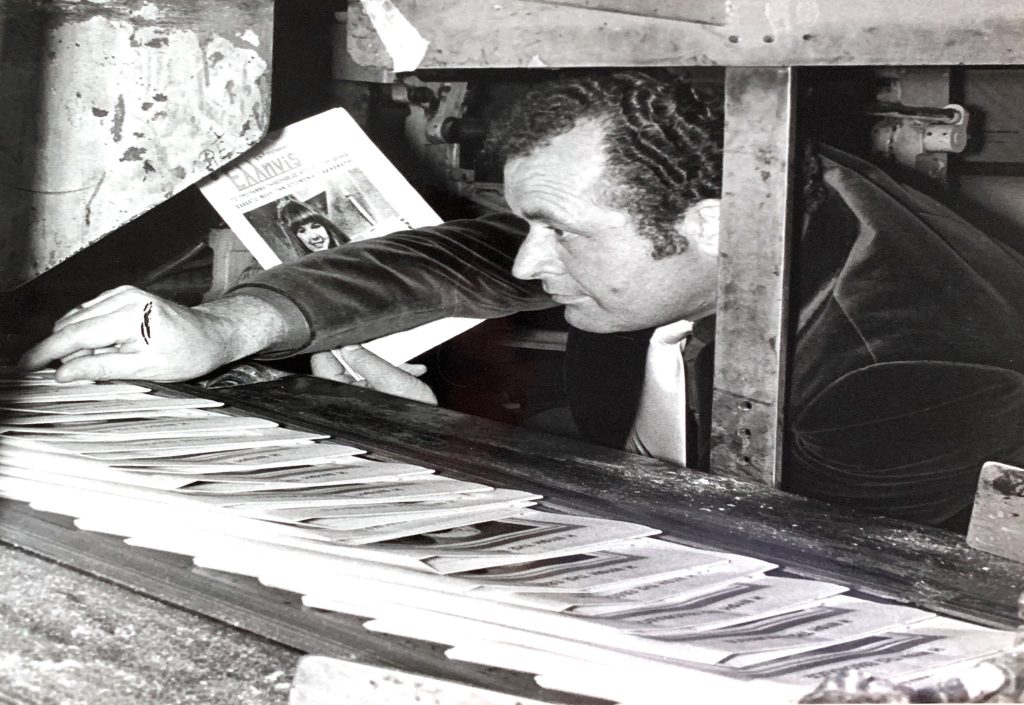

By 1958, Mr Skalkos was an expert of both the sewing needle and the driving wheel. He didn’t know it at the time, but he was also on the threshold of becoming a legend in Australia’s publishing and printing world.

“I got into printing by accident,” Mr Skalkos always said.

He had paid 50 pounds for his business cards to be printed when one of his driving students, Bob, took him to the closing down sale of a printing shop opposite Sydney’s Town Hall. Mr Skalkos ended up buying a pedal-powered press for 75 pounds, and had it delivered to his Kensington flat.

Despite not knowing how to use the printing press at first, Bob taught Mr Skalkos and Hellas Press (later Media Press then Foreign Language Press) was born. He was soon printing business cards, then wedding invitations and later commercial printing jobs.

The idea that changed Mr Skalkos’ life was a simple one – printing wedding invitations with pictures of one of the three Greek Orthodox churches in Sydney at Bourke Street, Darling Street and Abercrombie Street.

In 1965, he went to The Greek Herald (formerly Hellenic Herald), which at the time was owned by Alexander Grivas, and paid 12 pounds to place an advertisement to promote the wedding invitations.

“They put my ad but the rest of the page they put an ad for their own wedding invitations to kill my advertisement – the entire rest of the page. I was mad, I was upset…” Mr Skalkos explained.

Following this incident that Mr Skalkos deemed a betrayal, the Greek migrant decided to order his own typesetters and, knowing they would have taken up to 18 months to come, he asked the late publisher of Neos Kosmos in Melbourne, Dimitri Gogos, if he had anything second-hand that he could acquire instead. Mr Gogos did and after picking up the equipment, Mr Skalkos set up his publishing business.

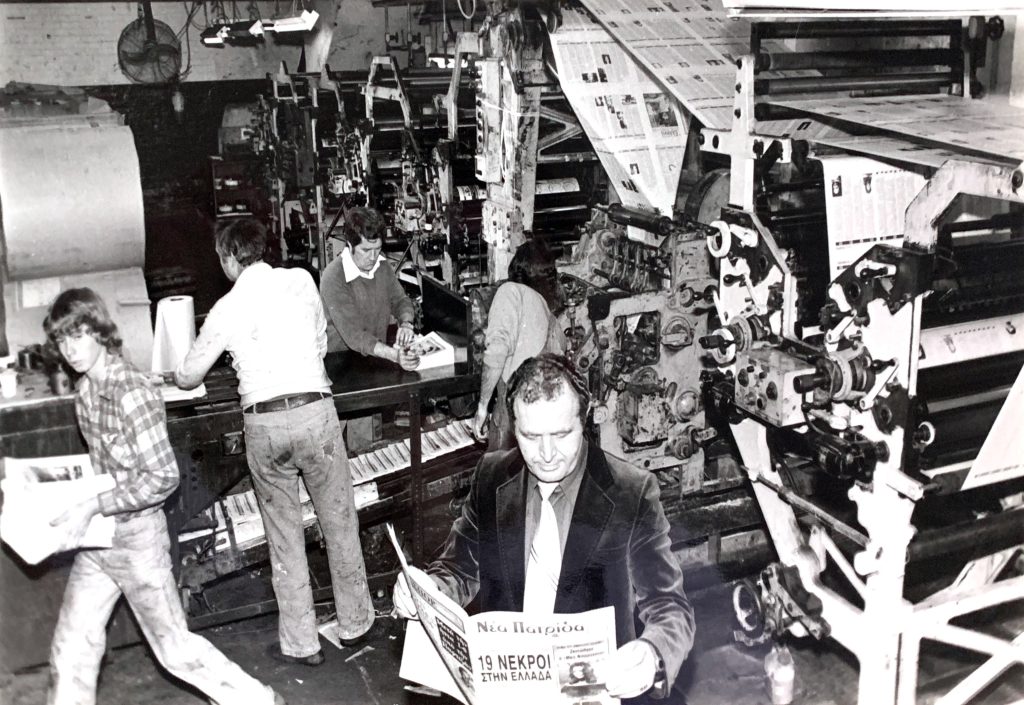

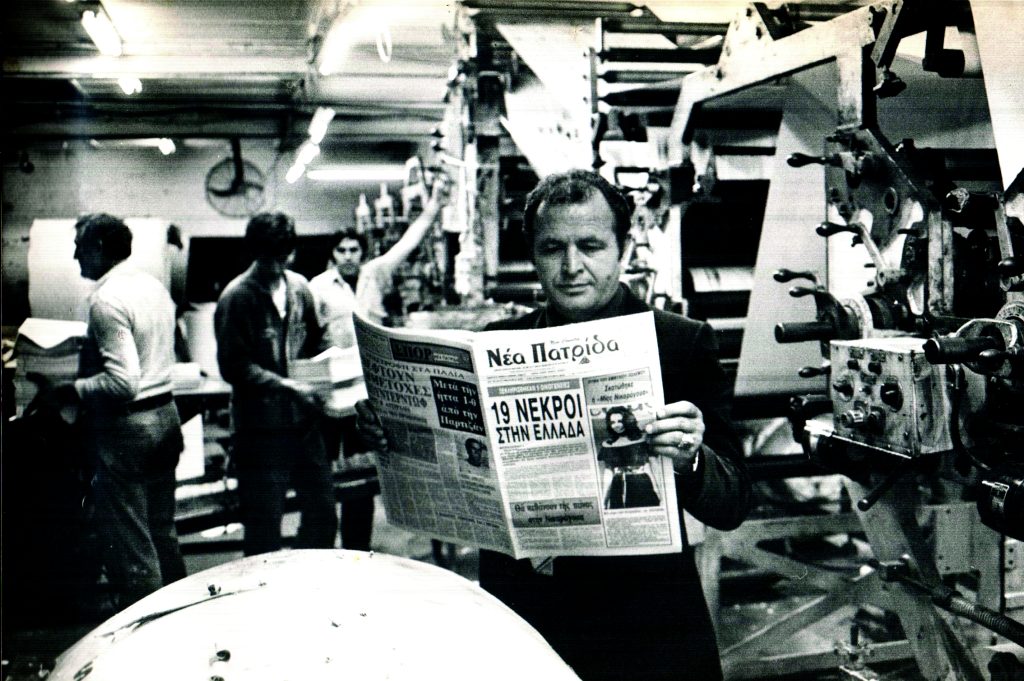

On 3 November 1966, Mr Skalkos started the Nea Patrida newspaper in direct competition to The Greek Herald. Νea Patrida was given out to readers for free as opposed to The Greek Herald which had a cover price cost. Mr Skalkos’ free newspaper quickly grew in popularity and became much more attractive to advertisers.

When asked about his competitors in Greek media at the time, Mr Skalkos said he was never afraid.

“We didn’t have strong competition because I was experienced, I had the facilities, I was never afraid to spend money to improve and update our equipment,” he said.

“Ethical competition is good business. The dirty competition is bad. I am a good fighter and I like to be at the top. I like to be first and that’s more or less why the business is successful. I’m not going for money, but I want to be successful in everything I do.”

No one can say Mr Skalkos wasn’t successful in business.

After launching Nea Patrida, Mr Skalkos continued to distribute the newspaper for free for 18 months before introducing subscriptions. In 1970, he eventually bought half of The Greek Herald for $66,000 and in 1972, he paid $186,000 for the other half.

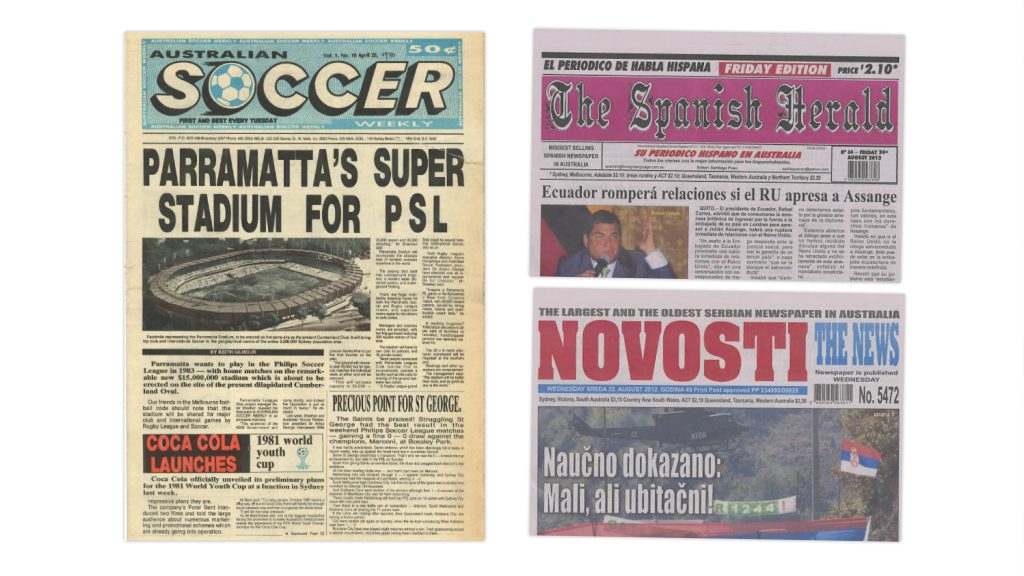

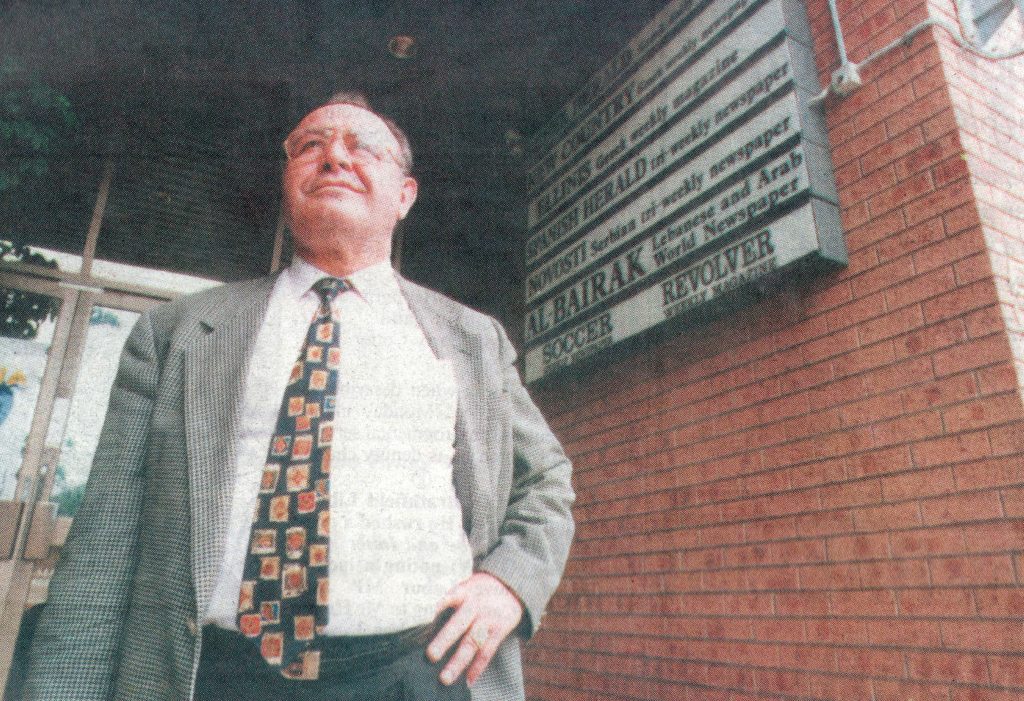

Mr Skalkos went on to buy a handful of foreign language newspapers and specialised publications, including the Serbian paper Novosti, The Spanish Herald and later the Arabic paper, Al-Bairak. He also started the Greek weekly magazine The Ellinis (which continues to this day), the Australian Soccer Weekly, and the Italian Il Mondo.

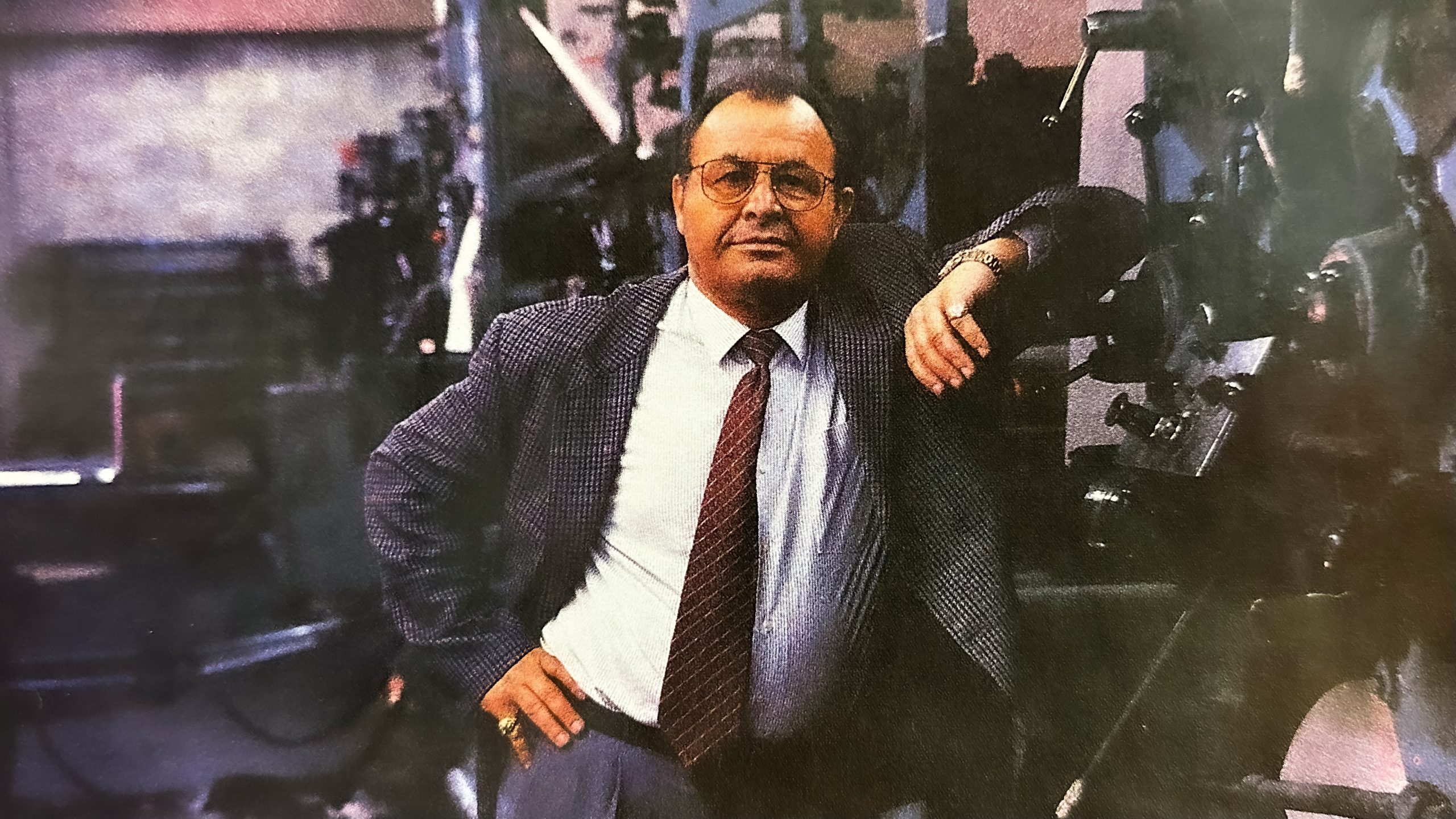

The print business also built up alongside the publishing, with Media Press having two printing presses, one each in Sydney and Melbourne. Mr Skalkos said he bought the first Goss Webb offset printing presses in Australia. He was also one of the first to abolish linotype and introduce electronic typesetting.

Media Press was soon printing more than 80 publications in over 40 languages, including prestigious News Corp Ltd titles such as the Sunday Telegraph and Sunday Mirror for a short time at the request of then-publisher Rupert Murdoch. The titles he printed accounted for more than three-quarters of the ethnic media in Australia.

For Mr Skalkos, the key to his success was hard work and keeping the needs of the ethnic communities he was writing for at the core of his publications.

With The Greek Herald, he spent weekends personally attending community events, taking photographs and placing up to four pages worth of coverage in the newspaper. It was something he took immense pride in.

“The Greek Herald is a bible to the Greek community. If The Greek Herald write about it, people believe it… because I wasn’t bought by Consulates, the Australian government, the Archdiocese, from nobody. I’m fully, fully independent. The people who read the paper and who advertise with the paper help me with what I do,” Mr Skalkos once said.

Skalkos’ controversies:

This independent stance saw Mr Skalkos become a controversial figure in Australia’s Greek community, and he became involved in several defamation legal cases. He also had a long-standing dispute with the late Archbishop Stylianos of Australia and the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia (GOAA) for almost 40 years.

But this didn’t stop Mr Skalkos. His motto was that in business, you couldn’t please everyone.

“It’s a hard game,” he said during his interview with the National Library of Australia.

“If you do something and you go against the big boys… you fight the war. It’s no good. When I try to do something which doesn’t affect the big people, they help you. This is why it’s a hard game and no one wants to do it.”

Diversifying ventures:

Despite the challenges Mr Skalkos faced, he continued growing his printing empire and even branched out into radio and television.

He first brought Greek television to Australia with his show Let’s Go Greek on Channel 10. As part of the show, Mr Skalkos brought out popular Greek singers and actors to perform.

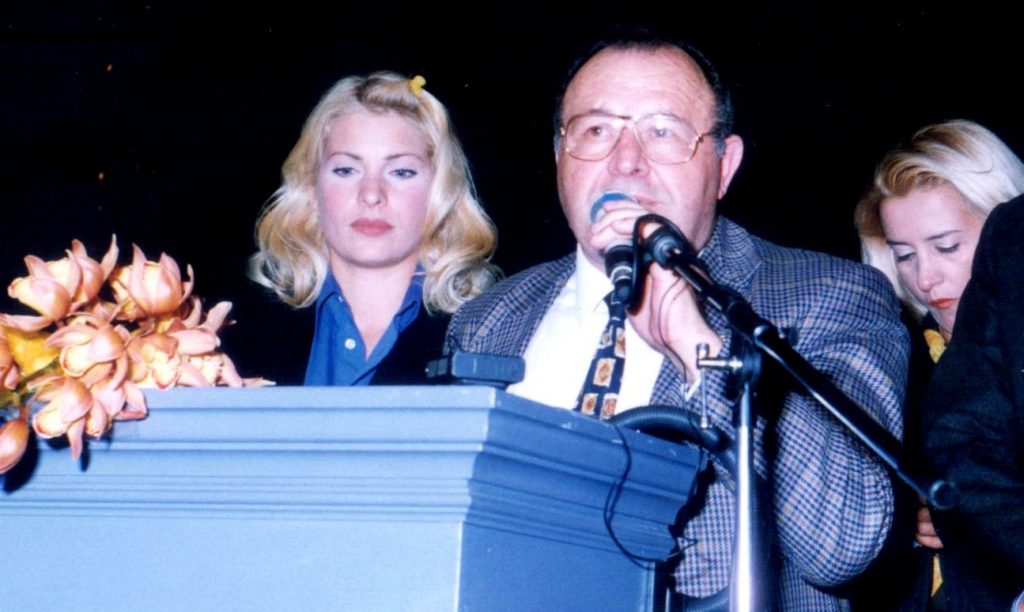

Mr Skalkos also organised concerts in Australia featuring artists from Greece, such as Yiannis Parios at the Sydney Opera House and the Sydney Entertainment Centre, which drew an audience of 15,000 people. Additionally, he hosted performances by Marinella, George Dalaras, Litsa Diamanti and numerous other renowned artists.

Mr Skalkos facilitated the introduction of the Greek channel Antenna (ANT1) to Australia. Subsequently, he organised a Miss Hellas pageant competition to boost Antenna’s presence in Australia, broadcast on Foxtel.

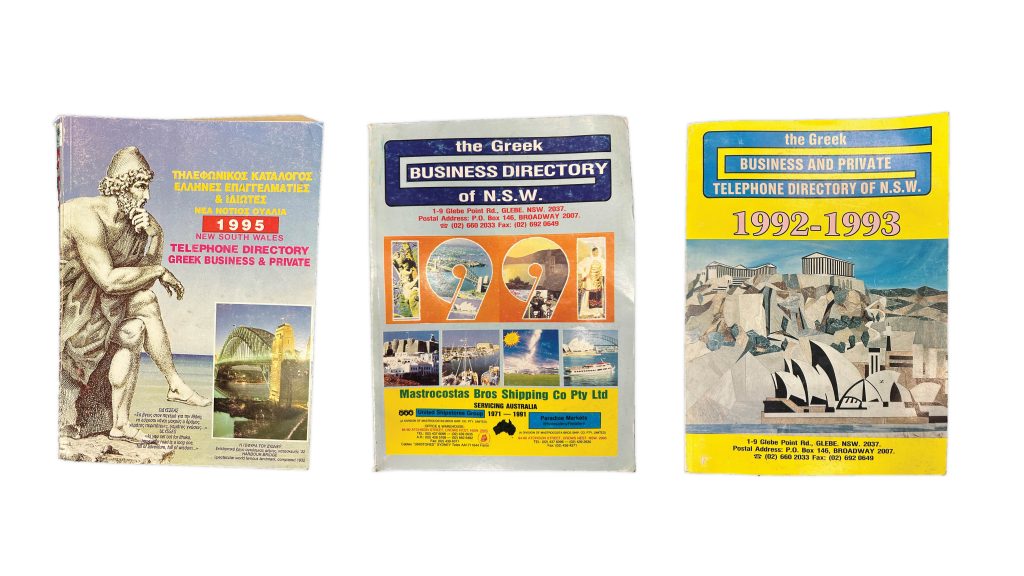

Demonstrating his commitment to connecting the Greek business community across the country, Mr Skalkos initiated the Greek Business Directory in Australia. To compile and maintain the directory, he deployed members of his team to travel extensively by car across Australia. In the 90s, Mr Skalkos also ventured into the travel industry with Alfa Travel, a travel agency located in Sydney’s Marrickville.

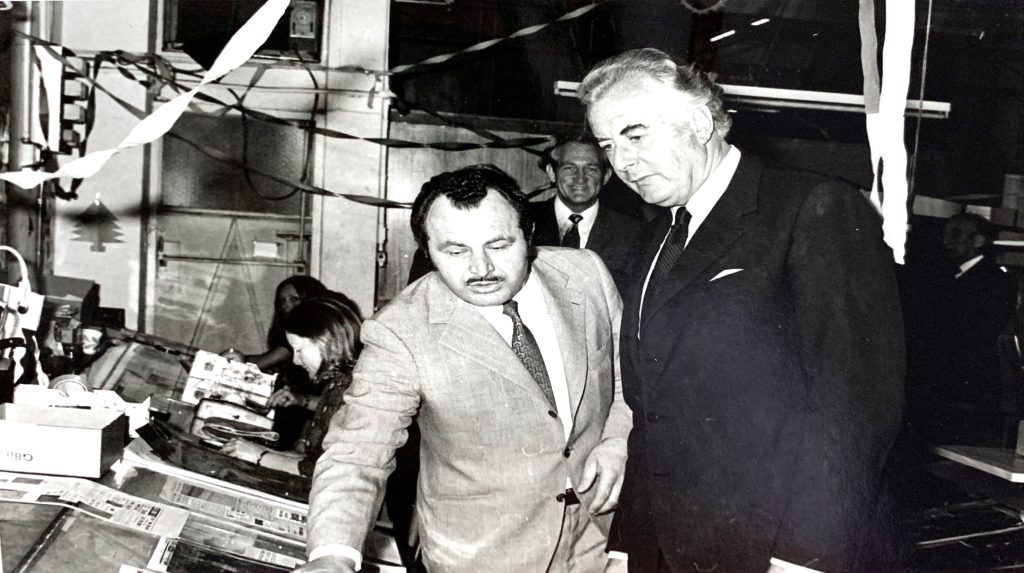

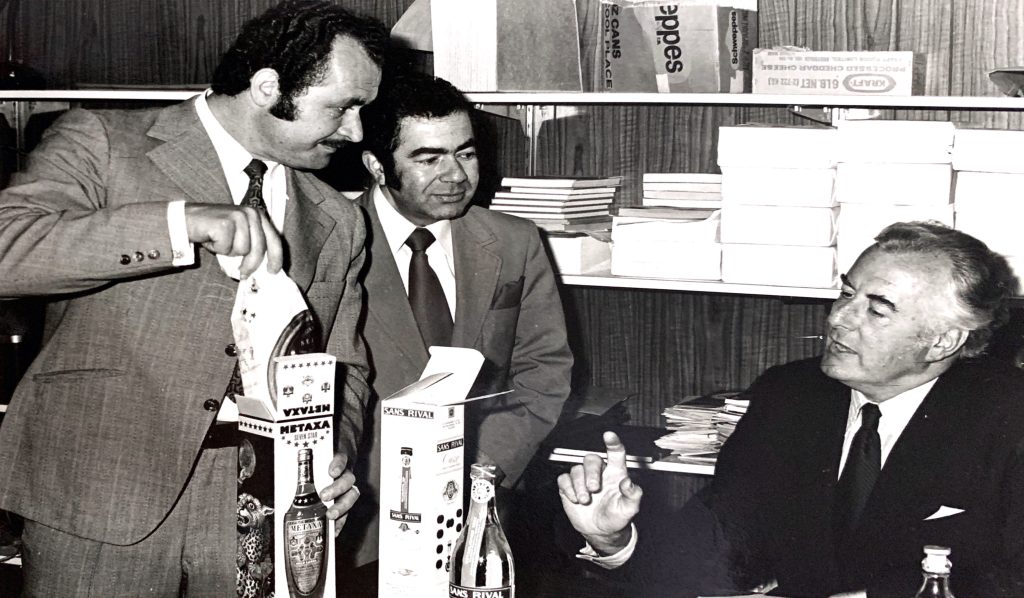

He worked closely with the late Gough Whitlam (a former Prime Minister of Australia), and the late Albert Jaime Grassby (a former Immigration Minister) to start a radio station for migrants. Mr Skalkos also started a 24-hour radio program ‘Voice of Greece’ with news direct from Greece, and he played a part in the launch of the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) in 1978.

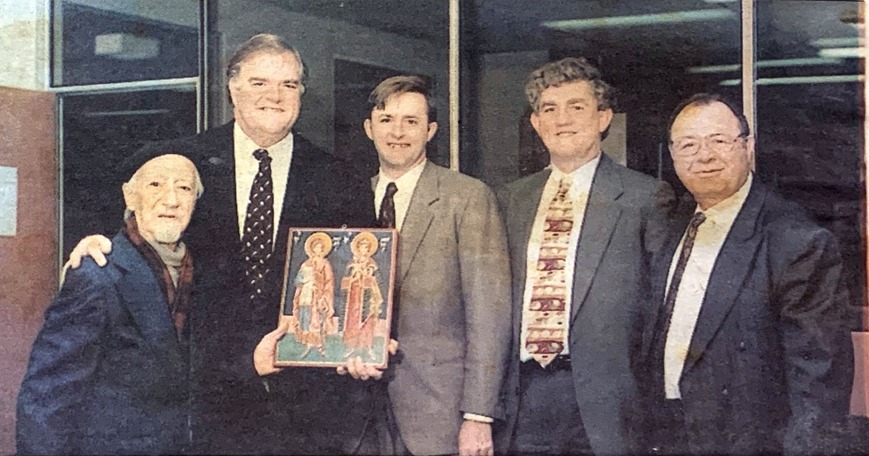

It’s clear that along his journey, Mr Skalkos met and became friends with some big players in Australia’s political, media and cultural circles. Besides Whitlam and Grassby, he also had ties to former Prime Ministers of Australia, Malcolm Frazer, Bob Hawk and John Howard, former Prime Minister of Greece, Antonis Samaras and media magnate Rupert Murdoch.

Mr Skalkos always spoke fondly of Murdoch, calling him a “good friend” with “guts.” When it came to politicians though, Mr Skalkos was never shy about his thoughts.

“I don’t believe politicians, I like to support people,” he said.

“If a person is good, it doesn’t matter what he believes. If a person does good for the country, it doesn’t matter what he believes – I don’t care. I never needed politicians, I never asked favours from politicians.

“Politicians come to you before the elections [and] a couple of weeks after that, they don’t know you, they don’t see you.”

With people not politicians at the core of his business model, it’s no surprise Mr Skalkos’ media empire continued to thrive despite being embroiled in numerous controversies. In fact, his ingenuity and innovation saw him become the longest-serving publisher of The Greek Herald.

“I changed the history of newspapers in Australia. I brought Greece to Australia. I fight for the good of the people,” Mr Skalkos said.

It’s a legacy that continues to this day as Mr Skalkos’ daughter Dimitra Skalkos is now at the helm of The Greek Herald and Foreign Language Press, leading the path towards sustainable digital transformation in an ever-changing media space.

Using her father’s entrepreneurship as an example to follow, Ms Skalkos has ensured The Greek Herald remains the only daily Greek newspaper outside of Greece. And with its 100th anniversary coming up, it’s clear there’s a bright future ahead – something Mr Skalkos would be incredibly proud of.