By Μary Sinanidis

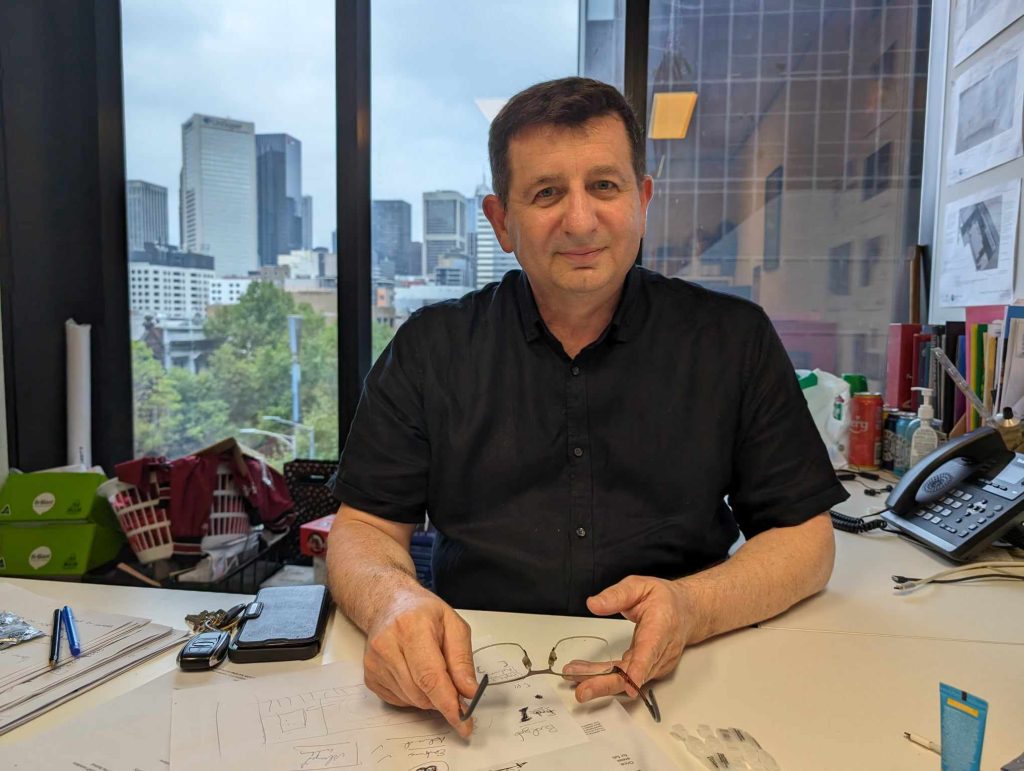

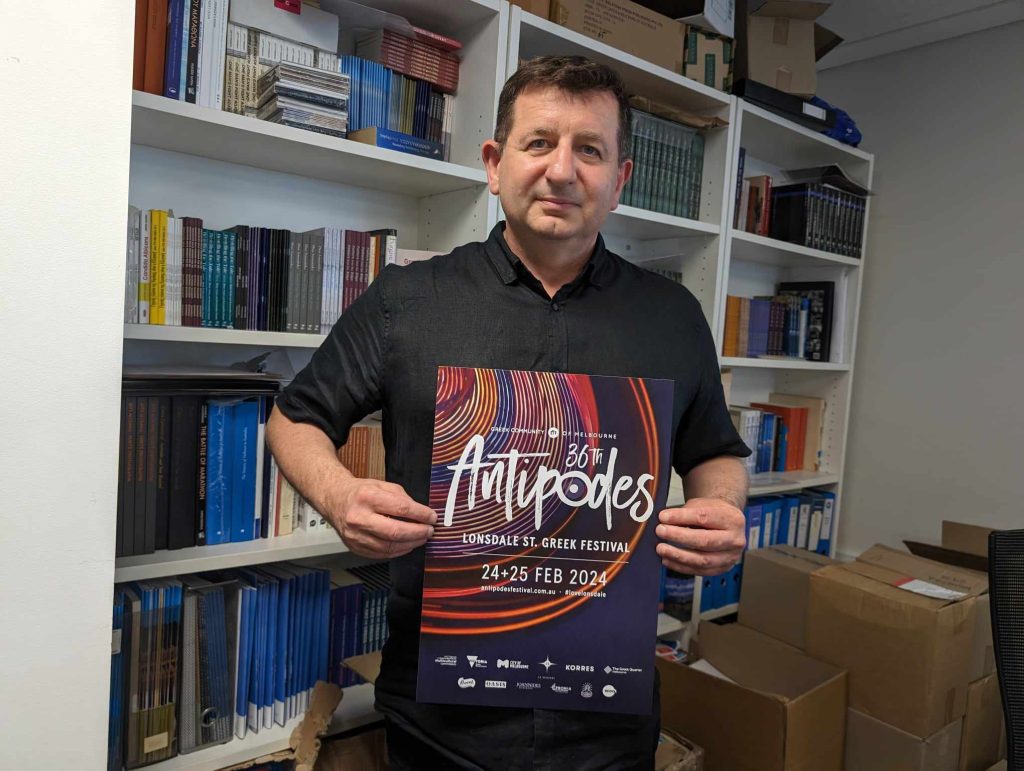

It’s Saturday morning, just one week before the Antipodes Festival on Saturday and Sunday, 24 and 25 February. Dr Nick Dallas is where you would usually find him at this time – at the Greek Centre on Lonsdale Street in Melbourne, where Greek language programs are taking place.

10-year-old Nick would have scoffed at this notion because he hated Greek school as a kid.

“I even wagged class a few times,” confesses the convenor of the Greek Community of Melbourne’s (GCM) education committee.

“Now I take the high moral ground and I keep reminding parents of the benefits of consistency so they can bring their children every week.”

At the Antipodes Festival, the pinnacle of the Greek community’s calendar in Melbourne, Nick will be sharing his story, encouraging others to learn the language and appreciate their heritage.

“Don’t assume everyone is familiar with the offerings of the Greek community. Some people have no idea. I get a buzz meeting these people at the Antipodes Festival and highlighting all the things available to them so that they can keep their heritage alive. That’s what I enjoy most,” he says.

“Greek school has come a long way from when I was a child and is offered in a very professional way here.”

Most of his generation found Greek language classes to be “traumatic.” In many cases, ears were pulled and faces slapped thanks to the pedagogical methods of ‘to xylo vgike apo to paradiso’ (the cane came from heaven).

Nick moved around several Greek schools in his childhood neighbourhoods of Windsor and Prahran.

“Forget the classy suburbs we know today; Prahran was a ‘Greek ghetto’ with close to 30,000 Greeks living there. Back then, we weren’t being discriminated against at school. We were the ones doing the discriminating. You were either a ‘wog’ or an ‘apprentice wog’,” he says.

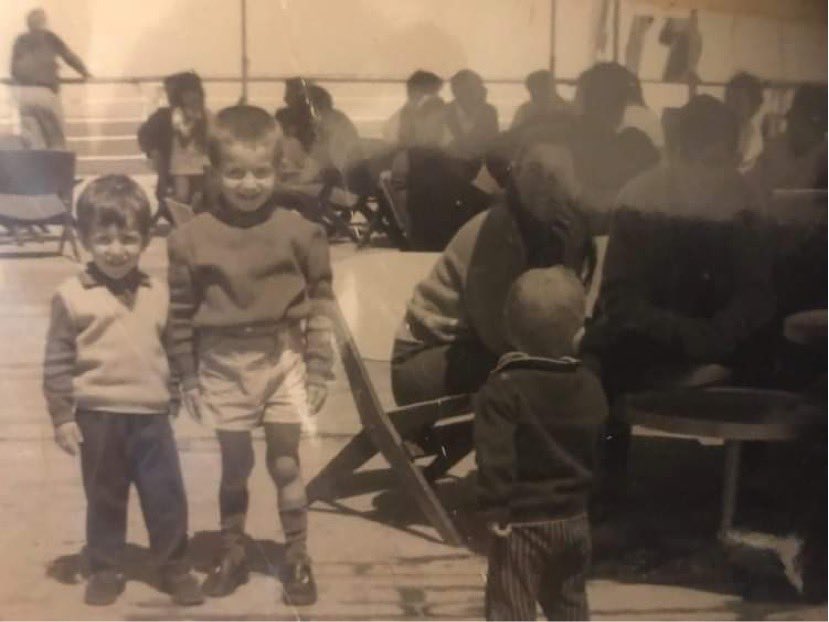

Nick speaks fondly of his youth despite being thrown into prep school straight after arriving from Karditsa, Thessaly, at the age of five in the early 1970s.

“I took to it like a fish to water,” he says, adding that it didn’t take long for him to become the interpreter for his parents.

Fresh off the boat

“I only have fleeting memories of the sea voyage on the Patris. My claim to fame on that voyage is that they closed off the pool after I fell in it,” he laughs.

The rest is a standard migrant story.

“My parents worked various factory jobs and, at some point, my mother worked for Red Tulip in chocolate manufacturing along with the mothers of most of my friends,” he says, admitting that he and his younger brother enjoyed her bringing home chocolates before the factory moved to the outskirts of Melbourne.

“The old building is now refurbished apartments with much of its history forgotten.”

Nick enjoys history and politics, the reason he completed an arts degree in Middle Eastern studies. It included classical Arabic and Turkish studies that lead to six months in Istanbul, where he stayed at a “minus five-star hotel” off Istiklal Avenue, a district once known to the Greeks as Pera.

“My stay was such an eye-opener, I really do believe that your average Greek doesn’t appreciate the complexities of Turkish society, the rifts and contradictions that exist within it,” he added.

This degree followed his science degree, sandwiched between his PhD in Chemistry and a Business and Economics degree.

“I was always a bit of an all-rounder. So, I kept studying to find myself and serendipitously ended up working for an educational publisher for the last 24 years. In the end, this was the perfect job for me, dealing with books across multiple subject areas,” Nick explains.

At the Greek Centre, it’s more of the same when it comes to the love of learning.

“As a board member you need to sit on a committee, but I find that I sometimes get a bit passionate about it,” he says.

Despite his passion for keeping alive his Greek heritage, it took a while for him to decide to run for elections with the GCM.

“When it was first suggested to me, it was a toxic culture with court cases and internal friction. But with the changing of the guard and more second-generation Greeks hopping on board, I became interested. The environment began to shift,” he says.

“If you spend your time doing something voluntarily, you want it to be productive and you want to achieve things.”

Nick enjoys the relationships created with teachers, visiting Greeks, diasporans from around the world, with students he meets as teenagers whom he bumps into later in life, as adults.

Servant leader

The phone rings in the middle of our interview. It’s Maria Bakalidou, principal of the schools of the GCM, who has just arrived at the Greek Centre. Soon she has him carting schoolbooks.

Pushing a trolley filled to the brim with Giati Ohi, Margarita and Klik is not on the job description of being convenor of the education committee, he jokes.

Nick is not one to limit himself to job descriptions. Unassuming and humble, he received the most votes at the last Community elections.

“I’d like to believe people respect the work I do both behind the scenes and in front of the scenes,” he says.

“So, if you garnered the most votes, why didn’t you become president?” I ask.

“I enjoy the role I already have. Education has been my passion, and something I’m very comfortable doing. Being a president means doing other things that you may or may not like… Also [current president] Bill [Papastergiadis] has been a fantastic president for the community and is the right person for this moment.”

Nick doesn’t like being in the limelight but prefers to lead from behind the scenes. Rather than rub shoulders with pollies on the Antipodes Festival’s stage, he prefers genuine conversations with people visiting the stall of the education centre. Amid chats with parents, he’ll pop over to the authors and academics to talk about the diaspora.

Benefits assessment

Asked about how Greece views the Festival and Melbourne’s Greek community, Nick suggests Greece may not have a true understanding of the different diasporas.

“Maybe Greece and the Greek governments perceive themselves as paternal figures to guide us, the children who have left. At the same time, another problem is that different diasporas don’t communicate enough among themselves and yet we have so much in common and a lot to share,” Nick says.

It is hard to tell whether the Festival can shift Greece’s perception of the diaspora, but it holds value when shifting Australian perceptions.

“The Festival operates at a loss, its operational costs are anything from $500,000 to a million dollars,” Nick says, pointing to the costs of meeting prerequisites in Work Health and Safety standards and security that amount to over $100,000 alone.

“Despite it being a Festival that needs to be subsidised, it is worth it, due to remarkable less-than-obvious benefits. Board members interact with politicians offering a chance for us to showcase the community, and there are benefits when it comes to applying for grants. It gives our community a much bigger reach thanks to the influential stakeholders who show up at the festival. And 90 stall holders of different businesses and social interests also benefit from participation.”