By Mary Sinanidis

Phil Cleary is many things: former teacher, football legend, anti-domestic violence activist, author, an independent member of Australian Parliament, and now embarking on a new venture as a documentary filmmaker. His latest project, titled “Gladys and the Brunswick Boys,” delves into the experiences of World War II ANZACs who fought in Greece.

This labour of love, thirty years in the making, is a culmination of meticulous research, raw footage collected over decades, and insightful interviews. Phil’s dedication to capturing this powerful narrative is evident.

“It’s ready,” Phil told The Greek Herald. “Over the past seven years, I have filmed in Brunswick, Greece, Crete and Austria. All I need now is a potential financial backer to get this powerful story onto a platform like Netflix. The footage I have is powerful.”

The genesis of this four-part documentary series traces Phil’s own family history, sparked by the discovery of his grandmother’s old photographs and documents. Reflecting on his childhood observations of his grandparent’s interactions, Phil recounts the story of his grandfather, Teddy Dorian.

Though it was Teddy who fought in Greece, it’s grandmother Gladys that Phil wants to name the documentary after. She spun at Millers Ropeworks and cared for her two young children including Phil’s mother, during Teddy’s internment in a German POW camp from 1941 to 1945.

Women’s strength during war

Many may believe that it was the brutal murder of Phil’s sister Vicki in 1987 that set off his search for social justice, but through Gladys we can see that the seeds were sown in childhood.

It was the resilience and determination of women like Gladys that fuelled Cleary’s advocacy for justice.

“Mothers wrote letters seeking answers,” he said. “In my case, in World War II, my grandmother was writing letters to the government, challenging them about her husband who came back from war and couldn’t work. It was the women who were campaigning and in many cases being harassed.

“My grandmother fought forever, year after year, with Veterans Affairs to have my grandfather looked after. She battled to get my grandfather a full pension, which he sort of got just before he died in 1964.”

Men’s post-war trauma

The post-war trauma endured by men like Phil’s grandfather is a central theme in the documentary series. Broken and emaciated, Teddy Dorian returned home to live in a bungalow behind the family’s Brunswick house. Despite challenges, Gladys remained steadfast, though their relationships lacked the depth they once shared.

“My grandmother accepted that they could not have a meaningful relationship, but she never pursued a divorce even though she had a boyfriend,” Phil said.

“My grandfather was an alcoholic, and he’d drink methylated spirits with his mates – a gang of them would meet near the railway line and drink cheap plonk. He suffered acute post-traumatic stress, and his mates did too. His friend Michael Parlon was run over by a train next to the Brunswick bars; he may have committed suicide. His other mate Jackie O’Brien died on Phoenix Street after a drinking session, and my grandfather died when he was 49 years old.”

Phil was 11 at the time, and didn’t realise the details or depth of his grandfather’s trauma.

Years later, he came across a group photo of the “Brunswick boys” on a hill in Austria at the Prisoner of War camp near Lienz.

“It was a remarkable photograph, just under 30 men in three rows, with the Dolomite Mountains on the border of Austria and Italy behind them and I was always interested in it. And eventually I met Billy Ottaway who had gone to war with my grandfather, Teddy, and his best mate Michael. Through Billy, I heard stories about the photograph and the camp. He told me about their capture near the Corinth Canal on the way to Kalamata,” Phil explained.

Billy Ottaway from Dawson Street, Brunswick, just around the corner next to Barry Street, went walking for months after the Corinth Canal was attacked.

“A Greek family took him in and he stayed there for weeks with the Germans passing by,” Phil said.

“Eventually, he decided it was too risky because they didn’t speak English and he didn’t speak Greek, so he gave himself up. And it was there that he came across my grandfather and his mate.”

Meanwhile, Teddy’s brother, Roy Dorian escaped aboard the Costa Rica from Kalamata but the boat was sunk.

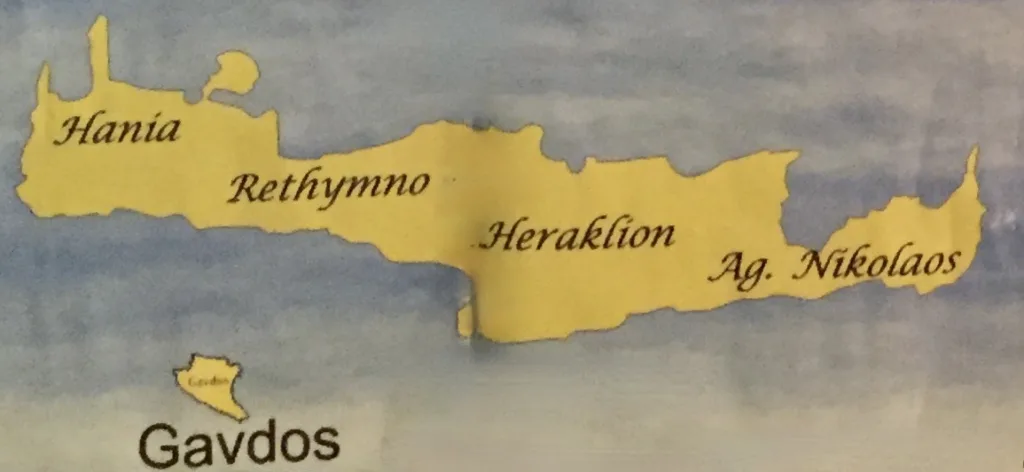

“He made it to Crete when the Germans invaded on May 20, 1941 and fought in Giorgoupoli and they marched to Sfakia. They stopped out of the village on the Battle of 42nd Street,” Phil said, referring to the infamous battle when the Nazis launched an airborne attack.

“He fought with Reg Saunders, the famous Indigenous Australian.”

Unfortunately for Roy, the boats had gone by the time he got to Sfakia and so he and a couple of mates found a dinghy and made their 11-hour escape to the island fo Gavdos, from there they walked for four hours to the South before coming across an invasion barge that took him to Egypt. Roy finally returned to Australia before being sent to Papua New Guinea to fight the Japanese, and that is where he finally died.

One son died, and the other came back after years in a POW camp.

A ripple effect

“I’m interested in the social history and the impact of these men’s wartime experience on their families and their local community. It’s a much bigger study than that of my grandfather and family,” Phil said.

A born storyteller, Phil also learned the art of filmography and travelled to Greece and Austria, revisiting the steps of the “Brunswick boys.” Along the way, he interviewed locals, capturing stories from different angles.

“Billy told me that when he was in a POW camp in Austria, he saw a US airman jump from his plane and die when his parachute didn’t open. And when I travelled to the village, I met Roland Damani, the former school teacher, who told me of the same US airman. I’ve filmed that scene, where he died, where his plane, the Angel, came down, and I know that Billy was not exaggerating,” Phil said.

Unseen footage, captured over years, will capture another side to WWII ANZACs. Phil hopes that, once released, “Gladys and the Brunswick Boys” will shed light on the profound impact of war across generations.

“All I need is a platform to share this footage with a wider audience so that viewers can connect,” he said.