By Dr Themistocles Kritikakos (Historian)

When Kastellorizians began to return in 1945 after their evacuation during the Second World War, the harbour, once alive with colour and trade, fell silent. My maternal grandparents stood on the deck of the ship that brought them home, their young children beside them and fellow Kastellorizians gathered nearby. Together they gazed at the island that had once been their home. They returned to ruins.

For much of its history, the island was deeply connected to the Greek communities of Lycia in south-west Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) through economic, social and family ties, including Livissi (now Kayaköy), Kalamaki (now Kalkan) and Antiphellus (now Kaş). My grandparents’ displacement was not new. My grandmother, Mihalakena Sakaris (née Taliangis), was from Livissi, and my grandfather, Themistocles Sakaris, from Kalamaki. They both crossed to Kastellorizo as young children because of the genocide of Greeks, Armenians and Assyrians in the late Ottoman period (1914–1923), during which they lost members of their families.

Having lost her father, my grandmother for a time lived in Alexandria, Egypt, with her uncle and his wife, later returning to Kastellorizo to be raised by her aunt. My grandfather lost his older brother during the deportations. He worked as a fisherman and seaman from the age of fourteen in Kastellorizo, earning his living from the same sea that had carried their family into exile, yet also sustained life.

The island in the First World War

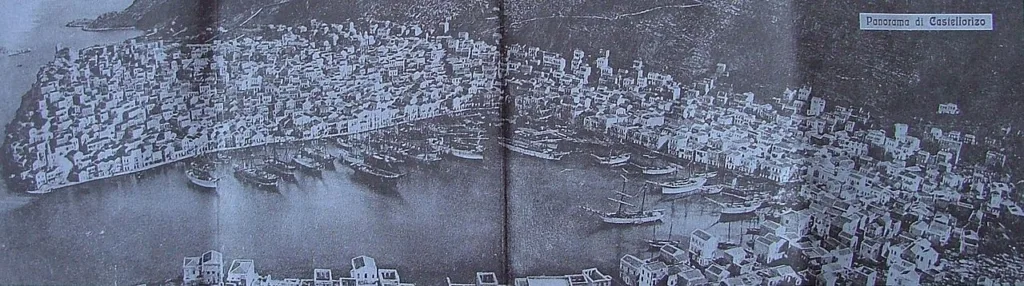

Kastellorizo, from the Italian Castelrosso meaning “Red Castle”, lies just two kilometres from modern-day Turkey. Once, goods moved freely through the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean, linking the island with distant British and Levantine ports, but that world of open movement gradually gave way to decline.

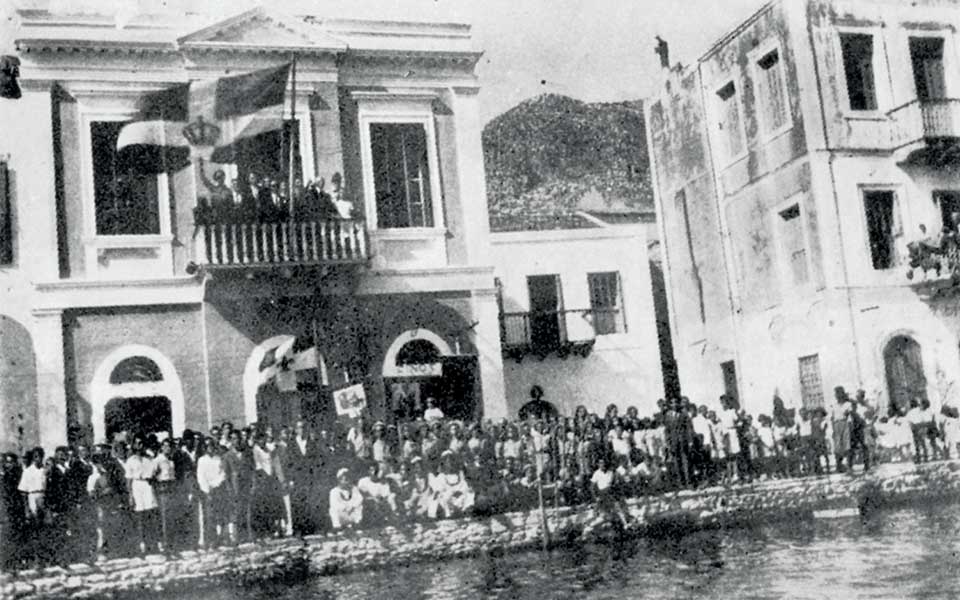

In the early twentieth century, the first major waves of migration to Australia began amid political and economic upheaval. Italy occupied the Dodecanese during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–12. Kastellorizo’s path to union with Greece was marked by violence and uncertainty. On 14 March 1913, the Kastellorizians declared a provisional Greek administration after imprisoning the Ottoman governor and his troops stationed on the island. The following month, Ottoman forces committed atrocities against the island’s Greek population, resulting in deaths and the burning of homes. The island thereafter endured alternating periods of fear and hope under successive foreign powers.

Kastellorizo came under French control in late December 1915, becoming a naval outpost and a target for Ottoman artillery. In January 1917, Ottoman coastal artillery on the Kaş heights opened fire on Kastellorizo soon after the arrival of a British seaplane. Over several hours, sustained shelling struck the town and harbour, causing widespread destruction and civilian casualties. Ottoman shore batteries sank the British seaplane carrier HMS Ben-my-Chree while it was anchored in the harbour.

The island was transferred to Italian administration in 1921, a status formalised by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which confirmed Italian sovereignty over the Dodecanese. Under Italian rule, policies of Italianisation curtailed Greek education and weakened the Orthodox Church’s role. An earthquake in March 1926 added further hardship, damaging homes and churches and prompting another wave of migration. The island’s population had fallen from perhaps 10,000 at the start of the twentieth century to around 2,000 by the 1930s.

War returns

When the Second World War reached Kastellorizo, the island became a strategic outpost. Its position offered a vantage point over Allied supply routes between the Middle East and the Aegean. In late February 1941 during Operation Abstention, British commandos briefly seized the island before Italian forces from Rhodes retook it a few days later. After Italy’s surrender to the Allies in September 1943, British troops returned; German air raids soon followed, and the civilian population was evacuated.

Across the Dodecanese, the war left deep scars. Islands such as Leros, Kos, Kalymnos and Rhodes endured bombardment, occupation, destruction and exile. In October 1943, around 1,000 Kastellorizians were evacuated by the British, first to Cyprus and later to Nuseirat in the British Mandate of Palestine, where families lived in makeshift shelters. Life was harsh: families endured shortages and disease, yet they preserved their faith, raising their children, marking feast days and welcoming new life even as illness claimed others.

In July 1944, while Kastellorizians remained in exile, a fire broke out on the island. It spread to fuel and ammunition stores left by military forces and consumed rows of homes and churches. The cause was never confirmed, but the destruction was total.

When they finally returned home in 1945, many are said to have leapt from the ships before they reached the pier, swimming towards the harbour in desperation to touch their island again. What they found was ruin; some collapsed in grief before the shells of their homes.

On 29 September 1945, the British ship SS Empire Patrol caught fire soon after leaving Port Said with close to 500 returning Kastellorizian refugees. Around 33 Kastellorizians and two crew members lost their lives. The sky lit red with flame as cries were swallowed by the sea. For those who had survived war and exile, the sea that once sustained life had become an agent of tragedy.

Much of the island’s merchant fleet, once its lifeline to the world, was gone, lost to war or seized for military use. Economic hardship and isolation drove many to migrate once again, seeking work and stability far from home.

Aftermath

The Treaty of Peace with Italy (Paris Peace Treaties, 10 February 1947) formally transferred the Dodecanese to Greece, and the act of union was celebrated on 7 March 1948. After decades of foreign rule and the devastation of war, Kastellorizo was Greek again, though its population had dwindled to about 500.

Life was difficult. The population had thinned, and the island was almost deserted. My mother, Vasilia, was born on Kastellorizo in the years that followed. She migrated to Melbourne in the 1960s, aged thirteen, with her older brother, younger sister and younger brother. She was part of the post-war exodus that would reshape the island’s destiny. The same uncle who had once cared for my grandmother in Alexandria was later uprooted from Egypt and again helped the family on their passage from Piraeus to Melbourne.

In Melbourne’s inner north, my mother worked in textile mills and other factories alongside migrant women whose tireless labour sustained the city’s post-war industries. Yet she always hoped to return to her island. My grandfather laboured at the brickworks in Brunswick, its towering chimneys visible across the red rooftops, while my grandmother persevered in raising a family through many hardships.

My mother’s three older sisters and two other older brothers had already settled in Melbourne, having migrated to Australia in the preceding years. My uncles initially worked in the sugar-cane fields of Cairns, North Queensland, while my aunties raised families under extremely difficult conditions before eventually settling in Melbourne. In the years that followed, many Kastellorizians and their descendants became influential figures in Australian public, business and community life. By the 1950s, Kastellorizian communities were thriving in Perth, Sydney and Melbourne, establishing associations, churches and cultural centres.

The island remains

Today, when the ferry from Rhodes turns into the harbour, the picturesque pastel houses are mirrored in the deep turquoise water, a calm surface concealing the memory of loss. The island’s original Greek name, Megisti (“greatest”), reminds us that although it is the smallest of the Dodecanese, it is the largest within its own small cluster, including Ro and Strongyli. The name itself speaks of endurance and pride, echoed by the vast diaspora that now thrives in Australia and returns to the island often.

Across the water lies Ro, where Despina Achladioti, the Lady of Ro, in quiet defiance, raised the Greek flag every morning from the late 1920s until her death in 1982. Throughout occupation, war, exile and unification, her devotion came to embody the spirit of all Kastellorizians.

The bond between island and diaspora remains unbroken. Each summer, Kastellorizians return from Australia — children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren who still identify with the island. They walk lanes lined with restored houses, light candles in rebuilt churches and gather by the harbour that once rose from debris.

Kastellorizians once looked across to the Asia Minor coast, where many of their ancestors had been uprooted, and wondered whether such times might ever return. Despite periodic tensions and provocations in the region, the people of Kastellorizo continue to maintain friendly relations with their neighbours across the sea.

The old school still stands, its walls worn by time yet alive with the memories of the children who once filled its courtyard. Bougainvillea spills over stone walls in bursts of colour, and sea turtles glide through the clear water below the quay.

My mother often speaks of those years. She remembers singing echoing across the island, laughter ringing through the narrow lanes and the scent of wildflowers. She also recalls memories of Papa Yiorgis (Father George), who had once been a chanter and later became the island’s priest, chanting in church alongside her older brother. A vivid memory, though, remained: my grandmother anxiously waiting on the balcony for my grandfather to return in his boat through the rough winter seas, weaving across the waves that broke against the front door of their home. It was a familiar story, forged in fire and carried by the sea.

Dr Themistocles Kritikakos is a Greek-Australian historian and writer. He holds a PhD in History from the University of Melbourne. His forthcoming book, Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian Genocide Recognition in Twenty-First Century Australia, will be published by Palgrave Macmillan in December 2025.