To truly discover the soul of Athens, Greece, it’s crucial to venture beyond the well-trodden paths and tourist hotspots. Delve into the contrasting realities that shape Athens’ contemporary identity, and you’ll find a city that’s reinventing itself.

In its most recent version, Athens has rebounded from more than a decade of turbulence: a crippling debt crisis, a brain drain, a refugee influx, and a global pandemic. These events have left their battle scars on the metropolis, and along with the city, Athenians have changed too. You can find them seated at their usual gathering spot – the local plateia (square), hubs in neighbourhoods that are an evolution of the Ancient Agora.

Most of the 3.61 million tourists who headed to Athens in July 2024 headed to iconic Syntagma (Constitution) Square, and chose to stay at picturesque neighbourhoods at the foot of the Acropolis. Inner-city areas like Mets, Koukaki, Thisseion, Petralona are now a tourist Mecca with picturesque Greek cafes, restaurants and souvenir shops.

Locals lament that they have been priced out of these neighbourhoods, with only the most affluent lucky enough to live among the boutique hotels and luxurious Airbnb rentals. A friend who moved to Kallithea after the Koukaki post-pandemic rental market skyrocketed tells me she hopes the transient tourist theme park does not reach her current home.

A city of contrasts

On the other end of the spectrum are Victoria Square, and those at Agios Panteleimonas, Agios Pavlos and Agios Nikolaos. These inner-city hubs are languishing in the aftermath of the refugee crisis that brought a tsunami of new arrivals.

Once-picturesque neoclassical buildings, former homes of dignitaries, have seen their glorious history scribbled out by graffiti. In these areas, it wasn’t the gentrification but the degradation that forced the original owners to leave.

Long-time locals, the few that remain, are sad to see a downward spiral engulf their homes, along with the subsequent drop in their property prices.

“I’m embarrassed to say I live here,” a resident of Agios Panteleimonas tells me before pointing to the neighbourhood’s potential with its iconic church, views of the Acropolis, and inner-city proximity.

These once-ordinary neighbourhoods are now ghettos of poverty, unemployment and social exclusion. The putrid smell of urine emanates from the heated summer sidewalks, while others ‘sun themselves’ on benches.

During the 2015 peak of the refugee crisis, controversial radical left wing SYRIZA minister Tasia Christodoulopoulou, who held the first-ever migration policy portfolio in the Tsipras government, was asked why undocumented migrants loitered at squares, doing nothing all day.

“There are no refugees (loitering) in squares,” she had said. “They just go out in the mornings to sun themselves.”

Local newspapers at the time also latched onto Christodoulopoulou’s suggestions that refugees provided a ‘tourist attraction’ for visitors.

“After all, tourists go wherever there are peculiarities,” she had said, sparking headlines and satirical cartoons. Her comments were made as 2,000 third-world migrants camped out at Victoria Square and hundreds more slept in makeshift camps at other inner-city squares.

Almost 10 years later, the SYRIZA government’s legacy can still be felt in the area.

Crime in the backstreets

With no set multicultural policy, Greece has a complex relationship with diversity due to the rapid influx of refugees arriving on dinghies and inconsistency in the government’s stance. The results of failed government policies are stark, with locals in the past having blamed the SYRIZA government for opening the “floodgates” without a plan in place. These days the situation has stabilised but inner-city regions have morphed into male-dominated ghettos filled with unique challenges, especially for women in terms of safety.

Gangs of men in these inner-city suburbs loiter to and from the seedy brothels on Filis Street, sliding through dingy doorways marked by lit lightbulbs even during the day. It’s the red-light district, though the lamps are white. What was once contained in Filis Street is pulsating outwards, engulfing 20-euros-a-pop prostitutes.

“They keep them there so these wretched men, deprived of women, have somewhere to go,” says my taxi driver as he pulls up to Agios Panteleimonas square.

There are several money transfer offices around the square, and another dozen or so in the side streets. These establishments are slowly replacing the pawn shops that sprouted during the debt crisis, allowing for migrants to send money back home. You can also pay bills and taxes at these establishments, as well as at OPAP betting centres and supermarkets.

Not all doom

With the sprawl of supermarket chains, iconic periptero kiosks are in decline while recycling units are popping up at nearly every square. In disadvantaged areas, you can see migrant and Roma children looking through rubbish for plastic bottles to pass through the recycling kiosks for a euro per 33 containers.

Another win are the cheap services offered by the multitude of nimble cobblers or tailor who swapped out a zipper on my jeans for 4 euros, while a 5-euro no frills haircut proved comparable to those of any fancy saloon.

Ethnic restaurants aren’t much to look at but offer affordable exotic delicacies. My interest is piqued by a rally of men pouring out from Syrian-owned Al Zaim onto Acharnon Street to enjoy chicken shawarma for 3.50 euros.

“It’s clean, affordable and delicious,” they say, and they aren’t wrong!

Though iconic cultural venues like Rodon and Trianon are a distant memory, a number of edgy theatre venues like Theatre Art 63 and Theatro Prova are sprouting within walking distance of the National Theatre of Greece, housed in the neoclassical Ziller Building on Agiou Konstantinou Street, just off Omonia.

The National Archaeological Museum, a beacon of hope, is also on this grittier side of town. A breath away from Victoria Square, the Hellenic Motor Museum can be seen from Maria Callas’ home currently being restored.

Canadian-owned Montreal is a little pottery/hairdressing studio that would be right at home in Glebe. Granted, the region’s redemption from a third world ghetto to an edgy Fitzroy-esque vibe may still be a long way off but seeds of change are constant.

Nothing stands still.

The changing face of neighbourhoods

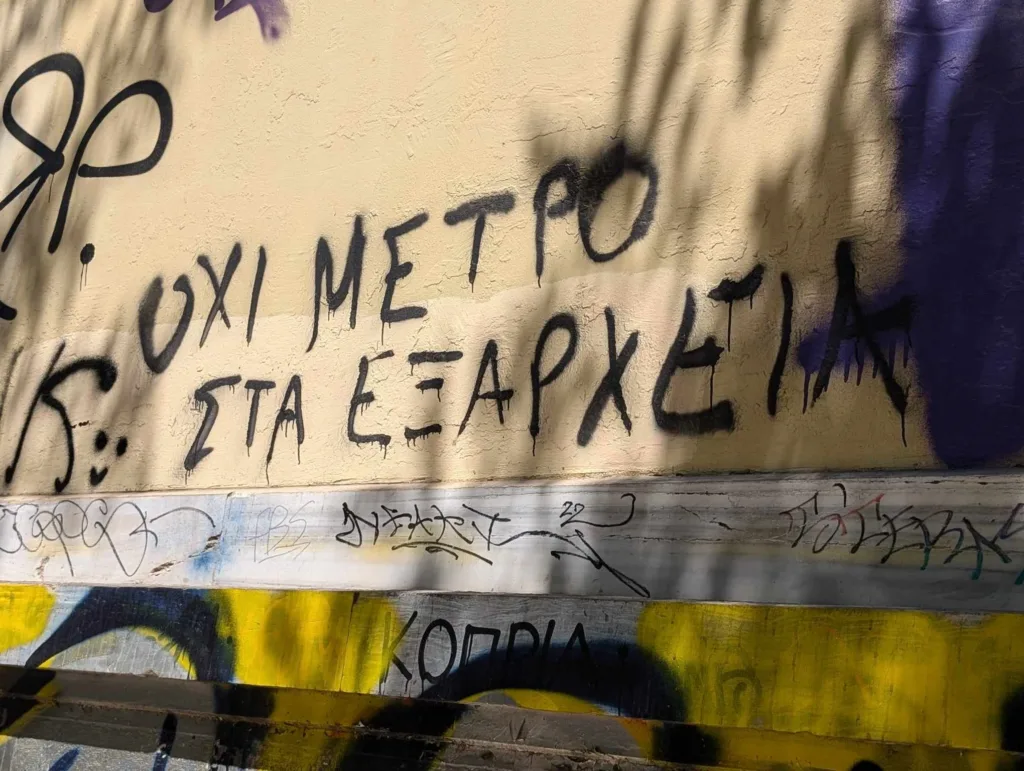

In nearby Exarcheia, where singer Marina Satti filmed her Mantissa video clip, gentrification has been steadily hammering away. Where anarchists and misfits once thrived, law and order are being restored.

Travel agents no longer warn tourists to avoid the area following the slow flushing out of hooded anarchists who would occupy buildings to rebel against taxes, capitalism, or any constitutionally determined political system.

Conservative New Democracy Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, a long-time critic of lawlessness in Exarcheia, declared war on anarchism in the area during his 2017 speech: “I will clean up Exarcheia,” he promised.

This was followed by a statement by Police Officer Union Chief Stavros Balaskas, who said: “If they give us a mandate, we will not only clean them up; but not even a mosquito will stay in Exarcheia.”

Once a haven for the resistance movement, the regular clashes between hoodlums and police have decreased. You can still find reminders of its history: political messages on walls, a faint aroma of pot as you pass by a window, the unofficially named ‘Alexander Grigoropoulos street,’ where the 2008 police shooting of a teenager sparked violence throughout Athens.

The voice of the resistance is being slowly drowned out by new bars, bookstores, florists, and concept stores popping up in buildings once dominated by squatters. A new crowd of Athenian hipsters, artisans, and high-brow intellectuals are moving in. They are less likely to light up a Molotov cocktail than they are a Cohiba.

Last year, Exarcheia even made its way to Time Out’s 40 Coolest Neighbourhoods in the World Right Now at number 31, with Melbourne’s Brunswick East (6) and Sydney’s Enmore (17) making the same listing.

Line 4 metro stop at Exarcheia, due for completion by the end of the decade, may well be the nail on the coffin as far as the area’s alteration from anarchy to arty is concerned.

Five minutes away is Kolonaki Square with its designer boutique stores and coffee shops where well-to-do Athenians would sip their coffee in winter months before leaving for Mykonos in summer. Still affluent, but you are less likely to see ladies with carefully coiffed hair walking their poodles in their Louboutins. However, you may find a Filipino housemaid or two taking on the task.

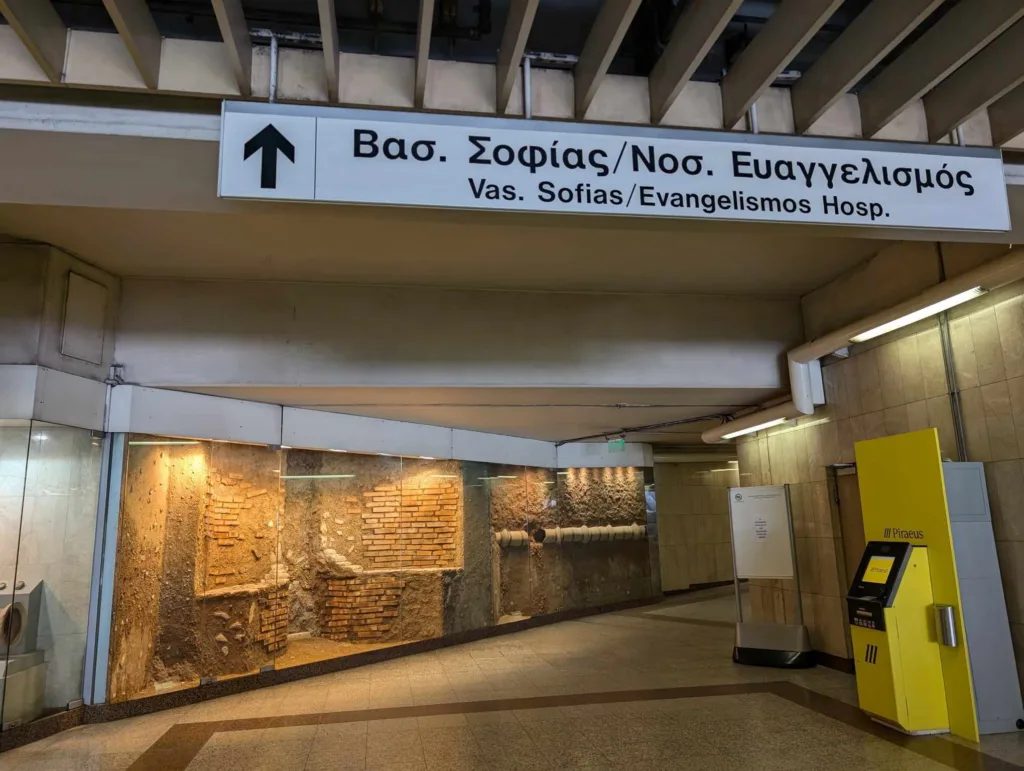

This summer, the square is dug up in preparation for the Exarcheia to Kolonaki line – once the antithesis of each other but getting closer. Strange bedfellows, almost as strange as the construction workers and archeologists working together as they dig through metro tunnels finding antiquities and then displaying these at metro stations where they were found.

Looking for ordinary Greek families

Though the metro is a great way to get around, you may want to veer off the metro line for a glimpse into the middle-class lives of Athenians.

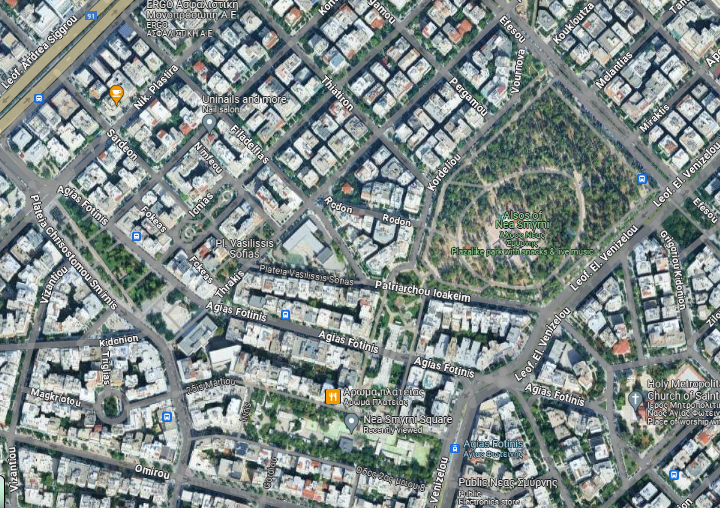

The most famous non-tourist square is that of Nea Smyrni. Sprawling over five acres, it is a square that fiercely retains its strong local character and intergenerational appeal: elders sip their coffee outside the Everest tyropita chain, young parents encourage toddlers to take their first steps, teens rush out from the local high school, nicknamed Onasseio after the suburb’s famous benefactor, Greek tycoon Aristotle Onassis.

It is a place where neighbours bump into each other and enjoy beverages in cafes by the fountains. Souvlaki shops like Lefteris and Crepa Crepa creperie have become local institutions. You may come across an odd toddler tantrum for an ice cream at Zuccherino, and adults head to Adonis, a café that has even inspired songs. Galaxias, a café hangout for young people in the 1980s, has been repurposed as a cultural centre. Each venue carries memories for those who spent their youth there.

Like Nea Smyrni, middle-class suburbs like Agia Paraskevi, Kaisariani, Pangrati and Vyronas have squares non-trodden by tourists.

Getting around

Public transport in Athens keeps getting better with the extension of its metro lines strategically placed as they link to bus, tram and metro arteries. The set-up is made even more convenient with digital signposts at bus stops telling you exactly when the next bus will arrive, and an app has also been created to take the guesswork out of waiting.

The price has remained stable at 1.20 euros for a standard ticket using all transport means for 90 mins (50 cents for seniors and students), and 4.5 euros for a one-day ticket, 8.20 euros for unlimited five days and a 3-day tourist pass is also available and includes transport to and from the airport. Despite the affordable prices, the honour code is tested as people rush to get in for free behind ticket-payers at gateways. Others leave their tickets on rails so that fellow commuters can make use of unused time left on their tickets.

Cabs continue to be notorious with drivers chatting on mobile phones while driving, whizzing through an occasional red light, a number refusing to turn on taxi metres unless asked, and though credit card payments are now a legal obligation, there are still cabbies uninterested in following the guidelines.

With GPS tracking systems now available, it is tempting to turn on your GPS but get ready for an insulted cabbie should you be caught. But with fares still being affordable sometimes it’s worth circling your way to the square.