As a young boy growing up in Australia, James Paniaras would attend ANZAC Day marches and “feel empty” because most of his friends had a “heroic” grandfather who had fought in a war, while he had no one.

All this changed when James was older and he started to pay more attention to important national events such as Greek Independence Day. He began to ask his aunties questions about Greece’s history until eventually, he discovered that he also had a “heroic” grandfather who had fought in the Battle of Albania.

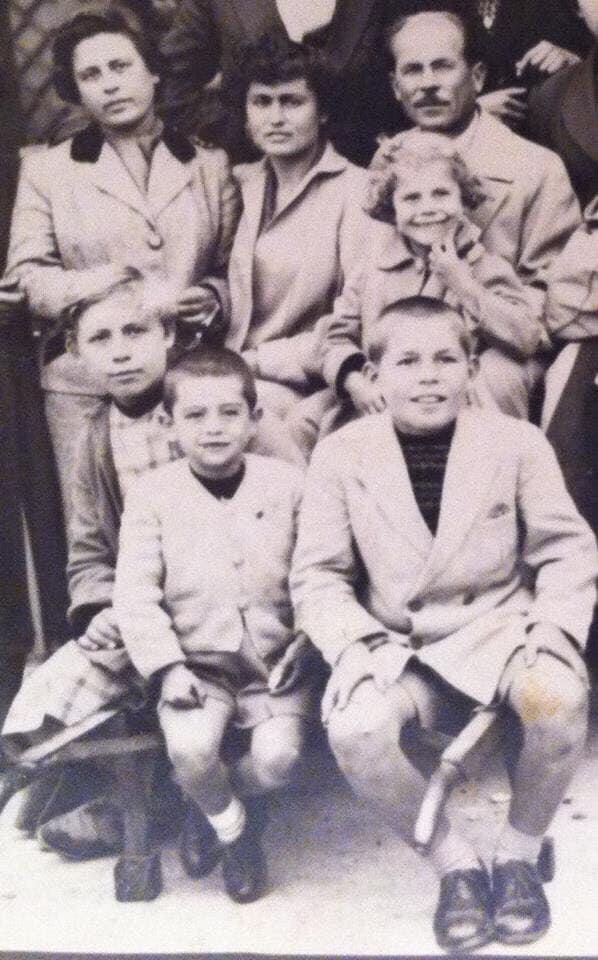

Petros Dimitrios Kalpaxis, James’ grandfather, was only 28 years old when war broke out between the Greek and Italian forces on October 28, 1940. Two days earlier, he had just celebrated the birth of his second daughter, Frida.

But, like many of his generation, once the bells rang out through Greece calling to service young brave men to fight for their country, Petros took up his arms instantly.

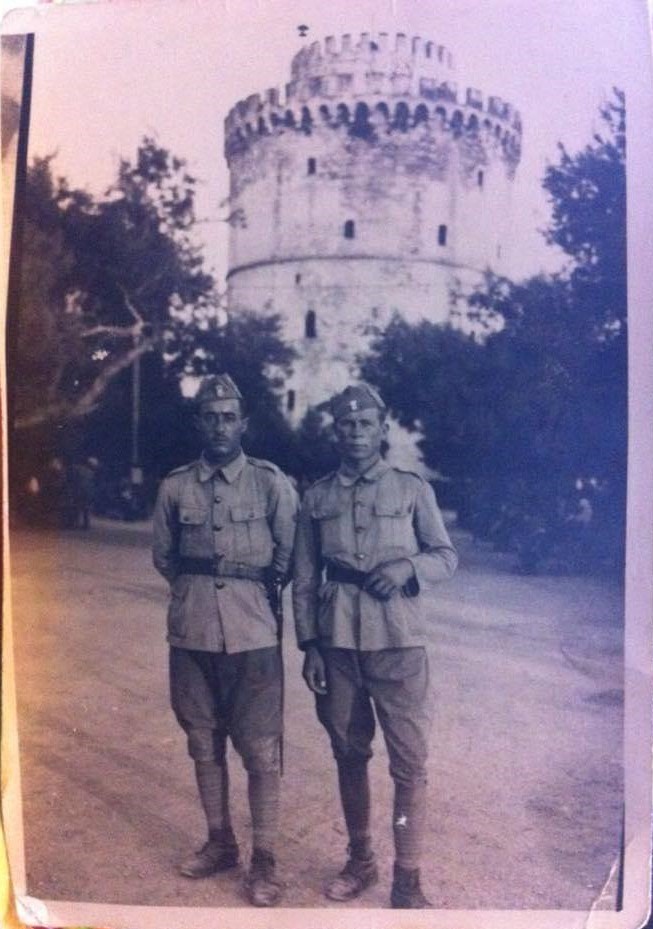

“My grandfather, who had completed three years of military service, left his family behind in late October and went to fight at Grama in Albania. He was a gunner and had to face extremely cold conditions, with snow so deep it was waist high as the soldiers walked,” James tells The Greek Herald exclusively.

Despite these conditions, the Greek army maintained a tenacious resistance against the over 100,000 Italian troops they were up against in Albania. This resistance had devastating impacts however, as many young Greek soldiers either lost their lives or were critically injured.

“One of Petros’ friends was mortally injured during a skirmish and died on the battle field. In the same incident, Petros was injured by mortar shell after a mortar bomb landed next to him. His finger and torso were injured due to the shrapnel,” James explains.

After 40 days of serving in Grama, Petros’ injury forced him to return to Corinth where he continued to serve in the hospital as a nurse and treated many soldiers with horrific, sometimes deadly, injuries.

Eventually, when Greece surrendered to Germany, Petros was able to go home to his village, Vasiliko, in Corinth and reunite with his family, including a daughter who had already become unrecognisable.

Petros was able to return to his village, Vasiliko, in Corinth after the battle.

Petros Kalpaxis also visited Thessaloniki. Photo supplied.

“When my grandfather returned, the people in the village grabbed a random baby and put it in Petros’ hands and said, ‘this is your daughter.’ He was sitting there cuddling her and then they laughed saying, ‘Petros, this isn’t your child. This is yours.’ And they brought my auntie to him,” James says.

“My auntie was a blonde baby. She was just completely different. So my grandfather had no idea who his daughter was because he hadn’t seen her in over two months.”

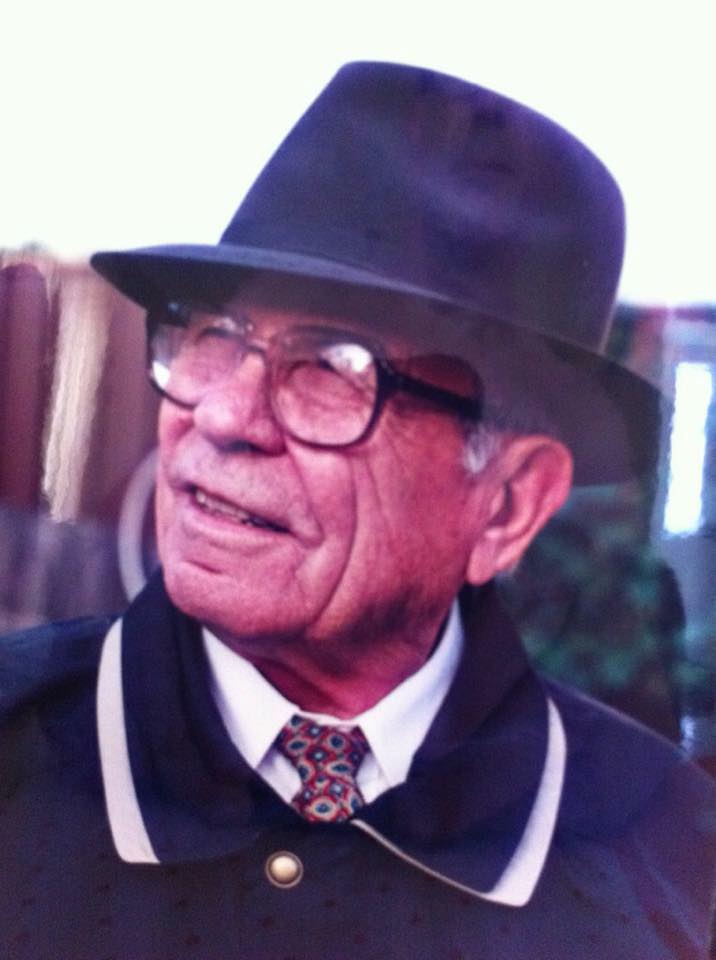

This, along with risking your life for your country, is a huge sacrifice that many would say deserves some form of recognition. But James says his grandfather and his comrades in Albania refused medals for their heroic actions.

“They talked about issuing medals and honouring the soldiers who had fought in the battles, but my grandfather and others said, ‘We don’t want medals because we did our duty. It was an honour to defend our country’,” James says.

“So they asked that the money for medals be used for the poor or for the widows of the soldiers who were killed.”

It’s these actions of selflessness and bravery which James says make him especially proud to call his grandfather a hero, even though Petros himself never consider himself one.

“I do remember on occasion, my grandfather sitting around the dinner table and an uncle of mine probing him and asking him what had happened during the war. But he would just choke up and he just couldn’t breathe and couldn’t talk,” James says sadly.

“But he would’ve been the first to say to me, ‘I’m not special. I’m just like everybody else.’ He would have wanted to dedicate this article to his friend who passed away in the battle, who never got to go home to his family, never got to cuddle his children.”

And that’s the most important thing of all. To remember and honour those Greek soldiers who fought valiantly against the Italians in Albania, inflicting an embarrassing defeat and setting an example for future generations of Greeks around the world.