By Kay Pavlou*

Greek Cypriot Demetrios Thavid, also as known Jim David, was born in 1943 in Nicosia, Cyprus. He arrived in Sydney in 1954. Aged 10, he began school immediately at the inner-Sydney suburb of Redfern.

“I didn’t like it all. The Australians hated the foreigners at that time,” Jim says.

At university he graduated in Medical Herbalism. The women in his family were his inspiration.

“My grandmother would send me to a mountain to get her the herbs she needed and she’d make medicines. I learnt about botanicals but I was only young. Now, I have two companies where I make natural medicines,” he explains.

Jim has relatives who were killed by the bombs dropped by Turkey on Cyprus in 1974. His ongoing sense of responsibility is relentless.

“It is my ethical duty to fight for the Cyprus Problem,” he says.

Jim was instrumental in the formation of Sydney’s branch of SEKA in 1975 – a national organisation pursuing a just and viable solution for Cyprus.

“I was the Vice President, then the President,” he explains.

Since then, hundreds of community members continue to protest against the illegal occupation.

Jim knew Gough Whitlam before he became Prime Minister in 1972.

“After the invasion, anything I asked of Mr Whitlam, about the Cyprus problem, he was always there to help,” he says.

When Greek cultural heritage was stolen from the occupied North, Jim looked for guidance.

“We had conversations with Mr Whitlam, how can we stop this theft and the sale of those stolen artifacts. He explained to me that Australia has to sign the UNESCO Convention for the Protection of Moveable Cultural Heritage,” the Greek Cypriot says.

Later when Jim was in New York, he saw some of the stolen mosaics from the Cypriot Church of Kanakaria. The Paul Getty Museum was interested in buying the 1600-year-old artefacts.

“I went to see them in person and advised ‘please don’t buy these mosaics because they are stolen and whatever you pay, you will lose.’ I made my point and we left,” he says.

Frustrated that political negotiations were at a stalemate, Jim made a bold move in 1991.

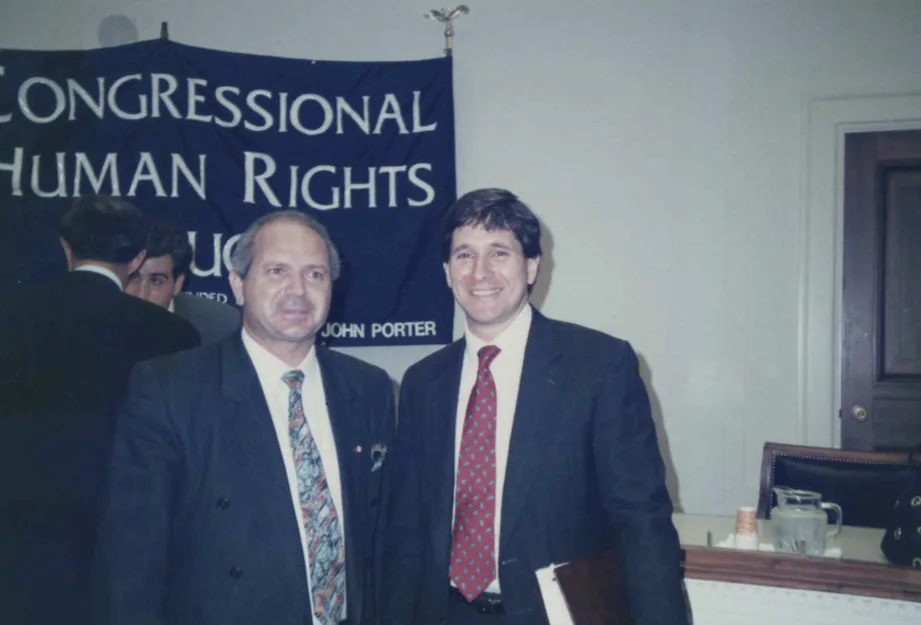

“I knew the only ones who could resolve the situation were the Americans. I decided to go to see… the Head of the CIA, William Webster… He was a very good person and he offered to help. I went to see Congress and asked aid to be cut from Turkey until they took responsibility for human rights, Geneva conventions and the United Nations charter. It was passed in Congress unanimously to stop aid to Turkey. They weren’t prepared to stop aid completely, but they did cut 375 million American dollars,” Jim details.

By the early 1990s, 20 years after the war, more than 2,000 Cypriots remained missing – both civilians and soldiers disappeared without a trace. Greek and Cypriot organisations across Australia signed petitions demanding knowledge of the fate of the ‘missing persons.’ Jim delivered them in person to the United Nations.

When met with indifference, Jim embarked on another mission. He put a $1 million reward for any significant information on the ‘missing persons.’ An Englishman came forward from the Royal Military Paratroopers and requested access to large scale maps.

“He was in charge of Kyrenia and he explained to me who was killed in that area. He marked the maps, where the graves were and how they were killed. The marked maps were shown to the so-called Turkish Cypriot President, Rauf Denktash, but he refused to acknowledge the deaths. Then, a chance meeting,” he says.

Denktash was staying in the same hotel as Jim in New York.

“I met him in the lobby, we had a chat and he invited me to go and see him. When I saw Denktash in Cyprus, he said the missing persons don’t exist. EOKA killed them. I said, ‘but Mr Denktash, here are the photos. In your hands. How could EOKA have killed them, if they are in your hands?’ He didn’t admit to anything,” Jim says.

Now Jim, nearly 50 years after the invasion, reflects, “the situation in Cyprus is very easily solved. Unfortunately, the current Turkish President, Erdogan, is intransigent. They want to take the rest of Cyprus. Because they have huge military power, they are slowly taking more, as in Famagusta – slowly, bit by bit.”

Jim believes the secret to the solution is to work closely with the Turkish Cypriots who are also oppressed by Turkey’s occupation in the North of the island.

When asked which is his homeland, Jim laughs.

“My roots are in Cyprus. I was born there, so were my great grandfathers. I love Cyprus very much. Australia, I love because it is my second homeland, that gave me opportunities to go forward in life,” he concluded.

*Jim David’s story features in Kay Pavlou’s new one-hour documentary Two Homelands. In the documentary, six elderly Greek Cypriots reflect on their war-torn homeland and life in Australia.