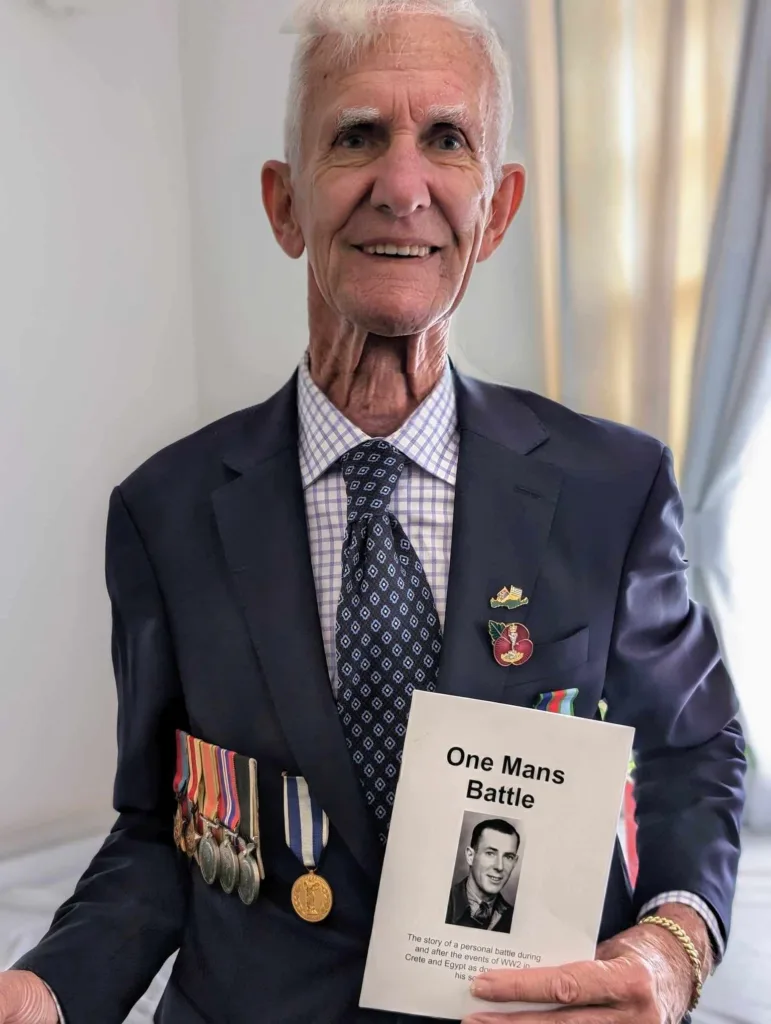

Peter Ford remembers the war stories his father, Fred (Frank) Ford, shared with him, raw memories etched with pain, loss and survival. They gushed out of him one day, pouring out from his soul into a 22-page book, ‘One Man’s Battle’.

“Even from a young age, I think dad wanted me to understand how futile war really is,” said Peter, who was born in 1944, three years after the Battle of Crete. “And it was still quite raw in my childhood. I even remember food rations.”

Frank served with New Zealand’s 22nd Battalion during World War II. He fought in Greece and Crete, witnessed atrocities, lost close friends and bore the physical and emotional scars for the rest of his life.

“It didn’t just affect him – it affected all of us,” Peter said, remembering his family life, with his charismatic dad and his bouts of PTSD.

In 1952, Frank rushed to Dunedin Hospital with an undiagnosed illness and vomited a ‘gelatinous black substance’.

“We believe it was the remnants of gangrene from months spent in a Cairo hospital after being shot in the stomach,” Peter said.

Frank enlisted in Palmerston North, completed basic training at Trentham, and was shipped off to England aboard the Empress of Britain. Instead of reaching Egypt as planned, his battalion was rerouted to Greece, then Crete—poorly equipped and under-prepared for what lay ahead.

The real battle began on 20 May 1941, when thousands of German paratroopers descended on Maleme and its strategically vital aerodrome. Frank’s unit was stationed at Hill 107, now the site of the German War Cemetery. He was part of the HQ company tasked with defending the area.

“Dad always said, ‘It was duck shooting season,’” Peter recalled in his book. “The paratroopers were easy targets hanging from the sky, but there were just too many. And the Allies had no air cover, no reinforcements. He said, ‘Courage and rifles are no match against planes.’”

One haunting memory stayed with Peter for life. At Galatas, Frank and three others were pinned in a foxhole for days under heavy machine gun fire. During a lull, one soldier lifted his head and was shot in the face.

“Dad never forgot his friend,” Peter said.

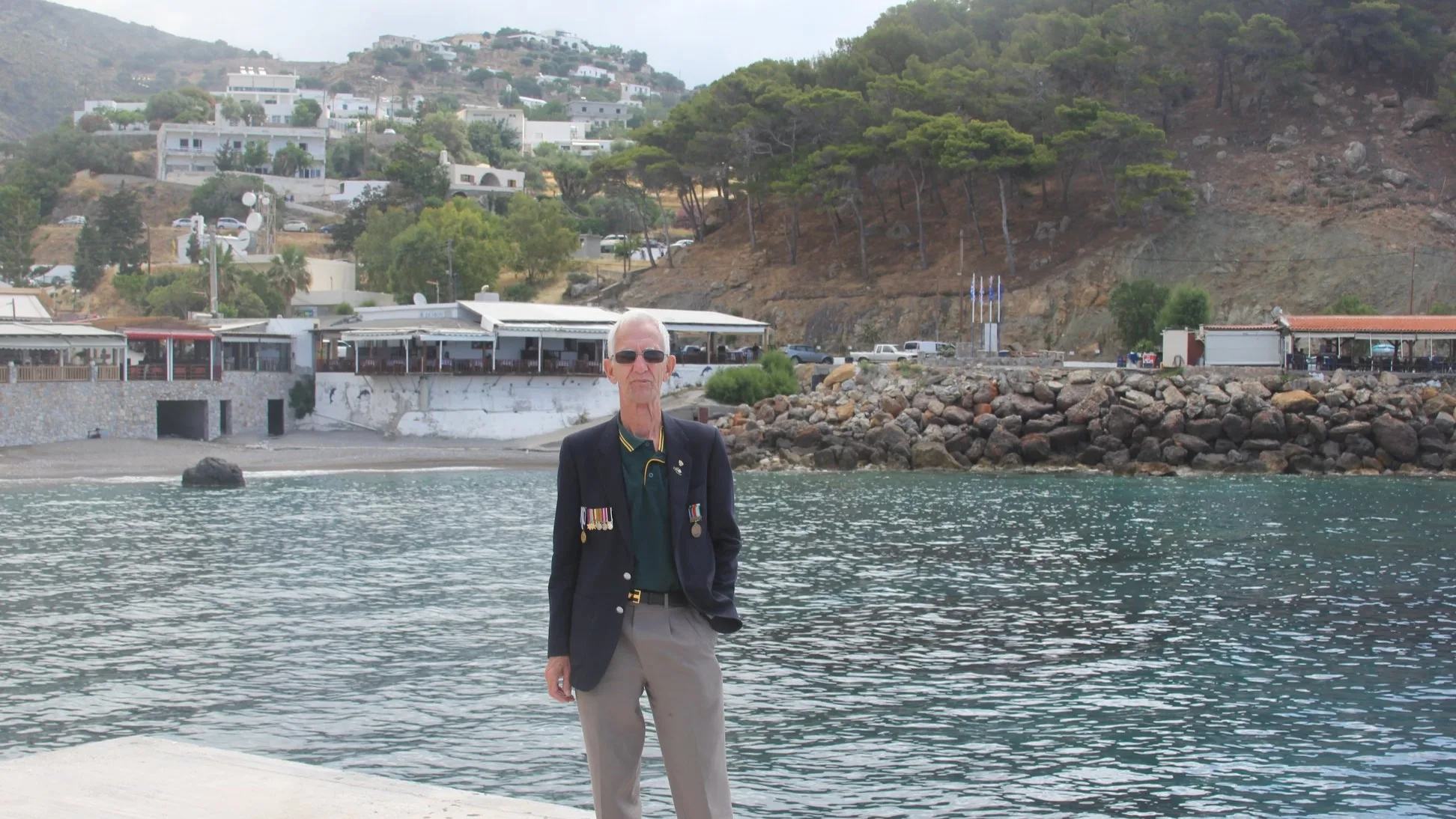

Peter visited the site in 1996 and again in 2015 when a two-storey house had been built there.

“Dad had told me there were two trees – an orange and an olive. He said, ‘When you go, pick one of each in his memory.’ I did.”

The horrors extended beyond the battlefield. Frank told his son about civilians, including women and children, being executed by German troops for helping Allied soldiers.

“What he described was brutal and graphic,” Peter said.

The Cretans, however, left a different impression.

“He spoke of their courage and kindness,” Peter said. “They hid him. Years later I met Alexandra, one of the children able to pass by German soldiers to smuggle food to my dad. She now lives in the United States, and were it not for her I may never have been born.”

Peter says Cretan hospitality still exists.

“Doors open for descendants of Allied soldiers. I am treated like a lost relative. It is almost like payback,” he said, remembering the family that brought in a priest and blessed him as part of their family, renaming him Panagiotis Giannis Alexandrakis.

Peter wrote the book to honour his dad and Cretan people, but also to tell the truth.

“The official histories are often sanitised,” Peter said. “That’s why I wrote ‘One Man’s Battle’, to give a voice to someone who lived through it. Some historians, what I call ‘hysterians’, rewrite or even plagiarise. I wanted the truth.”

Peter is now transcribing a 560-page wartime diary by another Anzac, Frank Lowe, opening another window into Greek and Australian history from someone who lived it “because the ones in the middle of it know.”

And, of course, so do the orange and olive trees still growing near Galatas – silent witnesses to a battle that never truly ended for the men who survived it.