By George Vardas.

Theo Angelopoulos is widely regarded as the greatest Greek filmmaker, having crafted an epic vision of modern Greece and the Balkans through his cinematic odyssey across its turbulent social and political history.

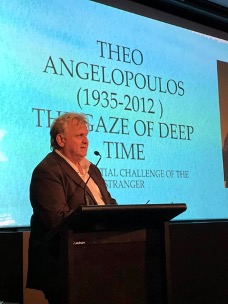

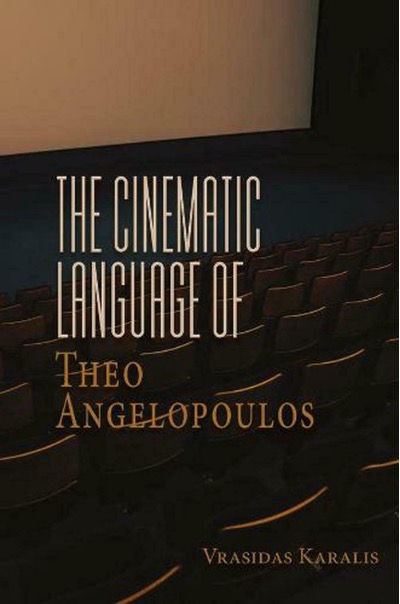

Professor Vrasidas Karalis, who holds the Sir Nicholas Laurantos Chair in Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies at the University of Sydney, has now published the definitive reference work on the late filmmaker. The book, The Cinematic Language of Theo Angelopoulos (Berghahn Press, 2021), was formally unveiled at a presentation staged at the National Maritime Museum in Sydney on 23 February 2022 as part of the Greek Festival of Sydney.

In an entertaining presentation, Professor Karalis spoke about his passion for the work of Angelopoulos and his first viewing of the 1975 epic, The Travelling Players (Ο Θίασος), an epic film of startling beauty and originality which attempts to tell the story of modern Greece through the wanderings of a travelling troupe in villages performing a traditional play of Golfo, the Shepherdess and covers the turbulent history of Modern Greece from 1939 to 1952.

When a young Vrasidas went to see the film, he was interrogated by his school principal who demanded to know if he had gone to watch “that communist film”. It was an act of resistance against political cultural censorship. It was very different to what he had seen before, a film that was abstract with sublime political and philosophical illusions, blending history and myth, realism and surrealism. In one scene, two members of the now disbanded troupe visit a friend after his release from prison to mourn the death of the revolution. The friend recites lyrics by a famous anarchist poet which has the effect, according to Karalis, of questioning if the adventure of the Greek Civil War was a justified rebellion against depression or a nihilistic utopian vision of self-destruction.

Rather serendipitously, I was first drawn to Angelopoulos as a young university student when I attended a screening of The Travelling Players at the Sydney Film Festival in June 1976. I was totally overwhelmed.

For me, it was a defining moment. I had just completed my first trip to Greece two years earlier in the winter of 1973/74 and was caught up in the immediate aftermath of the Polytechnique uprising, followed by the Cyprus fiasco and the fall of the military junta and the restoration of democracy (of sorts) in Greece. In one four hour sitting I saw it all play out, replete with Angelopoulos’ mesmerizing cinematic techniques of long takes and slow camera movements (which Vrasidas aptly describes as “energetic slowness”), continuous shots and ‘breaking the fourth wall’ where an actor turns to the audience and directly engages them in powerful monologues ranging from the exodus after the Asia Minor disaster of 1922 to the ravages of the Greek Civil War.

According to Vrasidas Karalis, The Travelling Players was and still is a grand masterpiece of European cinema, arguably the best film of the 1970s decade. The film majestically describes a turbulent period of Greek history with Brecht and Aristotle juxtaposed and the concept of time suspended. The beginning is the end.

Angelopoulos himself explained his disrupted narrative technique in an interview he gave in 2010 when he said: “Time present, time past is present in time future. We, our conscience, has time, is time.”

The late Dan Georgakas, a noted Greek-American historian, film critic and social activist, observed that in one scene a group of Greek fascists marches away from a 1946 New Year’s dance in full throated song to arrive in the same place in 1952 and we see that police beating strikers in one time period finish the task in another: a powerful survey in one take of the fascist undercurrents in recent Greek and European history.

In Vrasidas Karalis’ book, we learn about Angelopoulos’ life from his birth in 1936 to his unfortunate death (by accident) in 2012 and how some quite harrowing childhood experiences, including the arrest and disappearance of his father during the tumultuous events of December 1944 in Athens. The sudden reappearance of his father much later was greeted with an eerie, almost disbelieving, silence which resonates through some of Angelopoulos’ films.

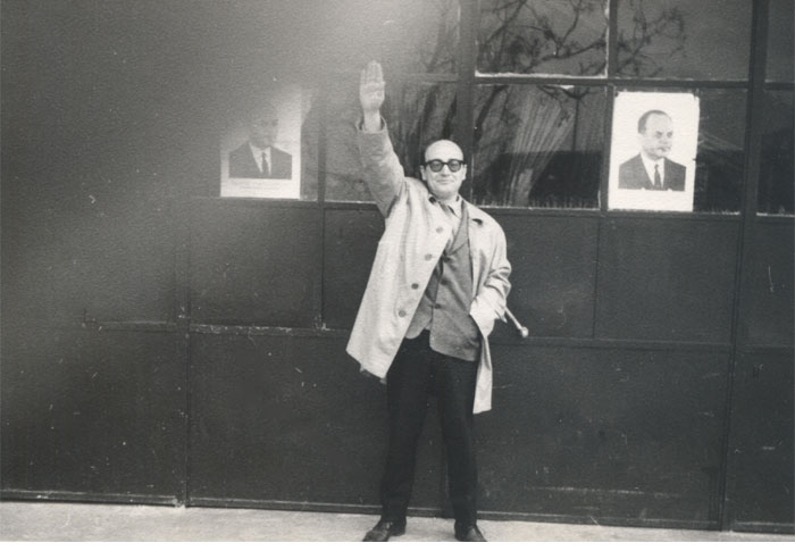

After studying in Paris Theo Angelopoulos returned to Greece and worked as a film critic for a left-wing newspaper until it was shut down by the military junta in 1967. It was then that he went behind the camera. Whilst he lived in Greece during the years of the junta he remained defiant and irreverent as ever, making the film Days of ’36 about the murder of a trade union activist shortly before the dictatorship of General Metaxas, under the nose of the fascist censors. A photo of Angelopoulos raising a fascist salute in front of shopfront images of the junta strongman Colonel Papadopoulos in Athens (taken in 1968) is telling.

Theo Angelopoulos produced a trilogy of history, a trilogy of silence, trilogy of borders and a (sadly) unfinished trilogy of modern Greece. Each confront different social, economic and cultural legacies, including Greece’s occupation and independence from Ottoman Turkey; Greece’s brushes with fascism; the advent of military dictatorship and the onslaught of the civil war; the plight of refugees in Europe and the repercussions of the Balkan wars.

Along the way we encounter Greek literature and mythology grafted onto modern Greek history and the director’s own life experiences fused into the art of the slow cinema. As Angelopoulos’ biographer and friend, Andrew Horton, reminds us, the films of Theo Angelopoulos matter.

And Angelopoulos was widely admired by many. According to Karalis, the great American director Martin Scorsese described Angelopoulos as a “masterful filmmaker” who really understands how to control the frame:

“There are sequences in his work – the wedding scene in The Suspended Step of the Stork; the rape scene in Landscape in the Mist; or any given scene in The Travelling Players – where the slightest movement, the slightest change in distance, sends reverberations through the film and through the viewer. The total effect is hypnotic, sweeping, and profoundly emotional. His sense of control is almost otherworldly.”

As Karalis showed through his presentation on the night, there are many memorable images in Angelopoulos’ films. The sheer visual poetry is simply brilliant.

There’s an extraordinary sequence in Ulysses Gaze in which a funeral barge carrying an enormous statue of a dismembered Lenin makes its way along the Danube, enhancing the mood of an “imploding world”.

In The Suspended Step of the Stork there is a scene where lovers separated across borders marry in a service conducted on opposite sides of a river. One of the actors asks “how many borders do we have to cross to get home?” Sadly, that question still resonates today.

In Landscape in the Mist, a symbolic, disembodied sculptured hand of a fallen deity is fished out of the bay in Thessaloniki and lifted by a helicopter into the sky

And then the two main protagonists of the film, young children who have been on a disrupted journey trying to locate the father that exists only in their dreams, approach a border crossing amidst the sound of gunfire. We then see them, hand in hand, running towards a tree which has emerged colourless from the mist. Is it a dream or is it real? The viewer is left to contemplate because, as with all of Angelopoulos films, there is no “The End”.

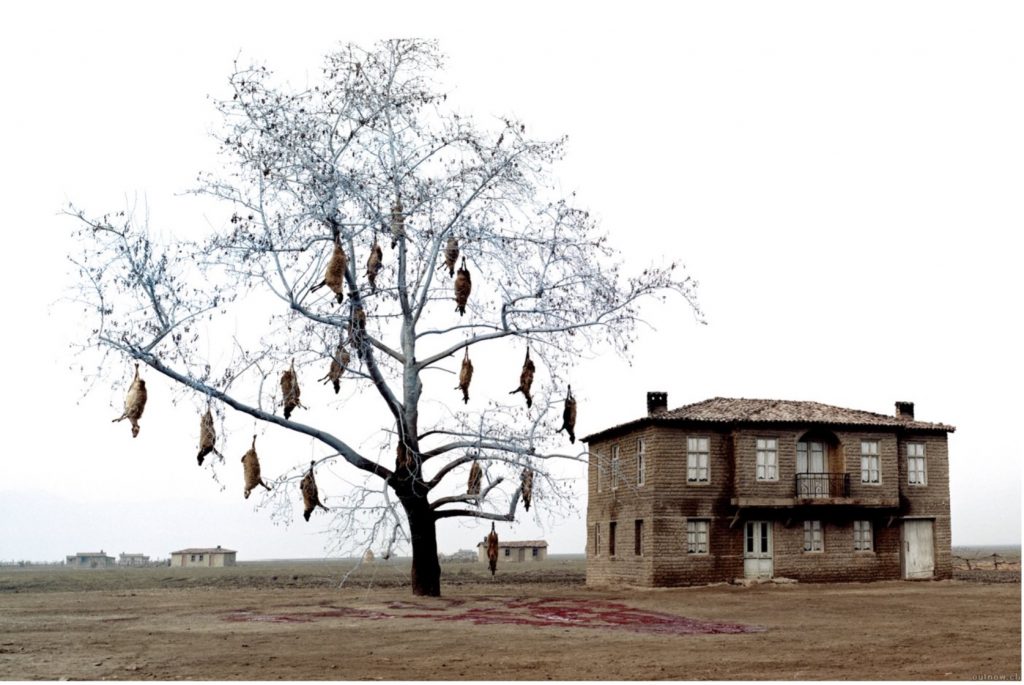

Then there is the haunting imagery in The Weeping Meadow of the tree with slaughtered animals over a lake with a sinking village.

And finally, in Eternity and a Day, a dying writer and young child approach a border. According to Vrasidas Karalis, the scene with people hanging on the border fence is probably one of the most astonishing and ominous pieces in modern cinema, a frightening depiction of the condemned struggle to escape which “stands too close to the everyday, tragic predicament of contemporary people”.

For as another critic observed, what makes us human according to Angelopoulos is found in traumatic memories, in the desire to preserve an imaginary beauty, and in eternal returns perennially frustrated.

Angelopoulos cinema is timeless. His epics of the chaos of Balkan and Eastern European dislocation (The Travelling Players, Ulysses’ Gaze, The Weeping Meadow) entail, according to Karalis, the “collapse of history” in a sea of futility and anarchy. The tragic events now unfolding in the Ukraine sadly reflect that “disintegrated and shattered reality”.

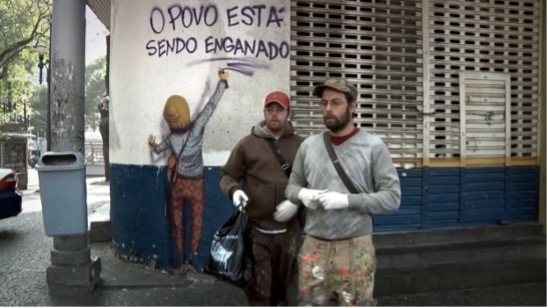

Towards the end of his presentation, Vrasidas Karalis screened an impromptu short film, Céu Inferior (Sky Below), made by Theo Angelopoulos in 2011 for the São Paulo Film Festival in Brazil as part of the theme “Mundo Invisivel” (invisibility in the modern world).

Angelopoulos captures from behind a Christian preacher proselytizing to gazing commuters in a São Paulo underground station and then films two street artists applying the final touches to graffiti on a wall with a poignant message: “the people have been deceived”. The Gaze of Lost Causes.

At the end of the presentation, an audience member asked if Vrasidas was an Angelopoulian or anti-Angelopoulian given that the late film director had created considerable controversy through his films, both amongst critics and peers. Vrasidas Karalis hastily assured the questioner that he is and always will be an Angelopoulian.

As I am.

The genius of Theo Angelopoulos lives on through this scholarly work by Vrasidas Karalis. His book takes us on an amazing cinematic and literary journey through the life and work of Theo Angelopoulos within what has been described as the “organic and borderless landscape of the Greek soul”.

Great cinema forever in the mist of time.