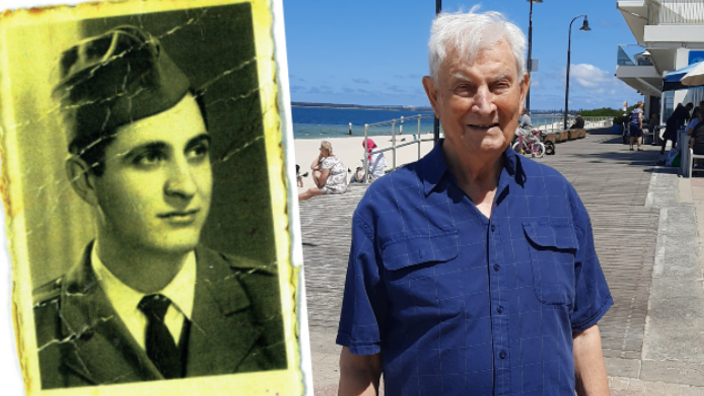

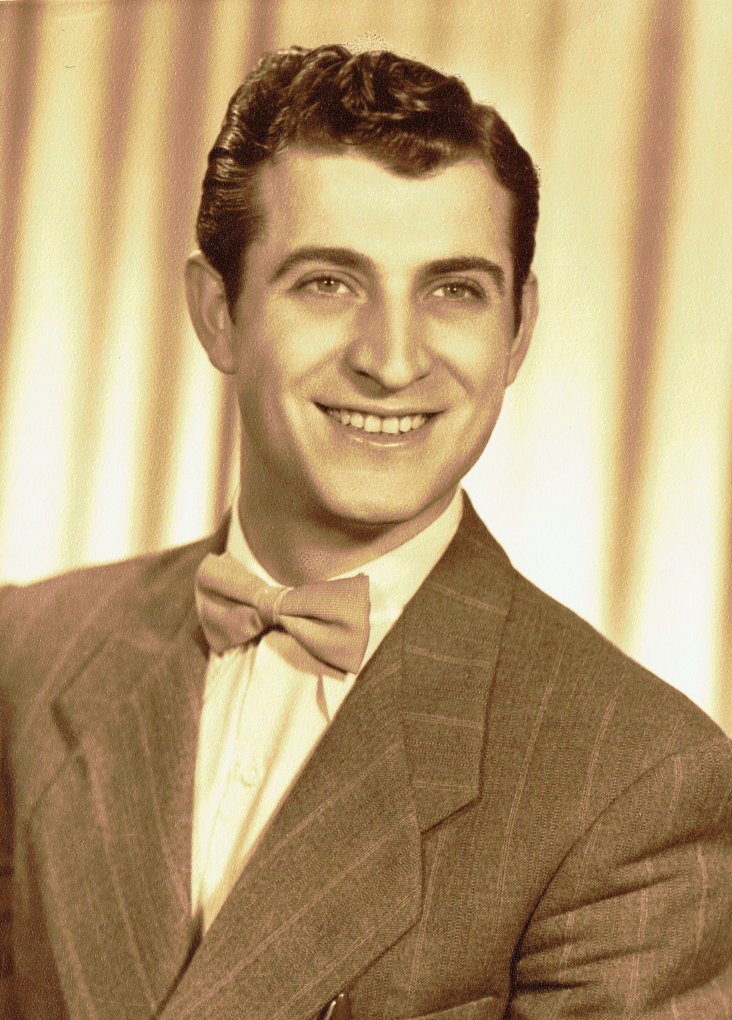

At 94 years of age, Dimitris Papadakis has lived through the Great Depression, the 9/11 attacks and now the coronavirus pandemic, but the one historical event which has stayed with him the most is October 28, 1940.

This date marks the moment when former military general and Prime Minister of Greece, Ioannis Metaxas, said ‘OXI’ (NO) to an ultimatum made by Italian Prime Minister, Benito Mussolini, an ally of Nazi leader Hitler. The subsequent invasion of Greece and outbreak of war saw Mr Papadakis’ life change forever.

“My family lived in Piraeus, the port of Athens, when the news came [about Metaxas’ response to Mussolini’s ultimatum]. I remember my mother taking me from our home to visit a relative in a different suburb of Piraeus who owned a radio at the time… for us to follow the news about what was happening,” Mr Papadakis tells The Greek Herald exclusively.

“We kept listening to it but what was really broadcast, mostly, was martial music and popular music just to keep the moral of the people high. But of course, automatically they started conscription.”

At the time, Mr Papadakis was too young to be conscripted to the Greek army as he was only 13 years old. But in the months that followed, and as news emerged of Greek troops fighting on the Albanian front, Mr Papadakis’ family began to return one-by-one to their hometown – the Greek island of Crete.

‘Swim as fast as you can’:

Mr Papadakis was one of the last of his family to make the dangerous three day and eight-hour trip to Crete. He visited Piraeus port every day to find a ship he could stow away on until eventually in January 1941, his chance to escape came.

“The interesting thing was that my brother-in-law was giving me advice when I said I’m going to sail to Crete. He said, ‘You look for a spot where the beams make a ‘T’ and stay under that because if the ship is torpedoed, that is the safest place that will not collapse very quickly. If the ship gets torpedoed, jump into the water and swim away from the ship as fast as you can’,” Mr Papadakis remembers.

Whilst Mr Papadakis didn’t have to take these drastic actions, being a stow away on the ship still came with other risks as well.

“I got on board the ship and when they came around and said, ‘show us your ticket,’ I said, ‘sorry I don’t have a ticket.’ They were worried about foreigners being involved in these things, so they called me in the middle of the night to interrogate me: ‘what is your name? what is your mother’s surname? what is your father’s name?’ All sort of things,” he says.

“Eventually they said, ‘we have to take you back to Piraeus. You can’t get off the ship when you reach Chania.’ But an officer saw me and said, ‘what are you doing?’ and I said, ‘they told me not to get off the ship.’ He goes, ‘go home.’ So I jumped out of the ship and went home.”

Crete under attack:

Only months later on May 20, 1941, Mr Papadakis came to witness the Germans invade Crete in the largest airborne attack ever attempted by Nazi Germany.

“I was at Kastelli [a village in Crete] and I saw the aircraft coming and then I saw the paratroopers dropping. I was young at the time and I thought, ‘this is an opportunity to see war first hand’,” Mr Papadakis says.

“I started running towards where the paratroopers were coming down. When I got there… the people of the town, whoever had a gun, ran and started the battle against the paratroopers. They killed most of them, about a dozen put their hands up and were taken prisoner.”

Eventually, the Germans managed to secure a foothold on Crete after roughly 12 days. The occupation saw Mr Papadakis put into forced labour by the Germans to help build another airport and the island also experienced a shortage of food.

“My father managed to get hold of some wheat from a relative in the country and I took it to the mill to be ground into flour. My mother did the dough and I took the bread to the local baker to bake and brought it back, but it was time for me to go to school so I cut a slice of bread and went,” Mr Papadakis explains.

“I was nibbling because I was hungry and the other children dobbed on me to the teachers. I got such a tongue lashing from the teachers. They said, ‘aren’t you ashamed? Everybody hasn’t seen bread for so many days and you bring bread here. Get out of here and eat your bread and then come back.’

“This was an indication of how things were at the time. Very, very hard and it lasted for quite some time too.”

Migrating to Australia:

Despite this, Mr Papadakis finished high school and joined the Greek army. He served for about 32 months during the Greek Civil War before he was discharged and migrated to Australia in 1953.

“In the beginning I didn’t like it. I said, ‘I’m going back to Greece.’ My sister said, ‘Look I understand but why don’t you stay for about six months to polish your English and see a little bit of the country so when you go back you can tell everybody where you’ve been.’ I thought it was a valid argument,” Mr Papadakis says with a laugh.

“By the end of the six months, my English improved and I could understand people… it became a little bit more like a normal life and I stayed.”

Mr Papadakis ended up working in a milk bar for a couple of years, before being a sales person at department store, Farmers, and eventually owning his own insurance broker firm for about 33 years. He also married “a very fine girl” and has three children and seven grandchildren.

Clearly, Mr Papadakis had a prosperous and happy life in Australia. But he still hasn’t forgotten his roots and that fateful day back in 1940 when Greece descended into an atmosphere of war.

“You do silly things at the time. You’re scared and you’re serious at the same time. It was quite a time,” he concludes.