When someone asked who is truly happy, Thales of Miletus replied: “Whoever has a healthy body, a sophisticated mind, and a teachable nature.” So recorded Diogenes Laërtius, also from Anatolia.

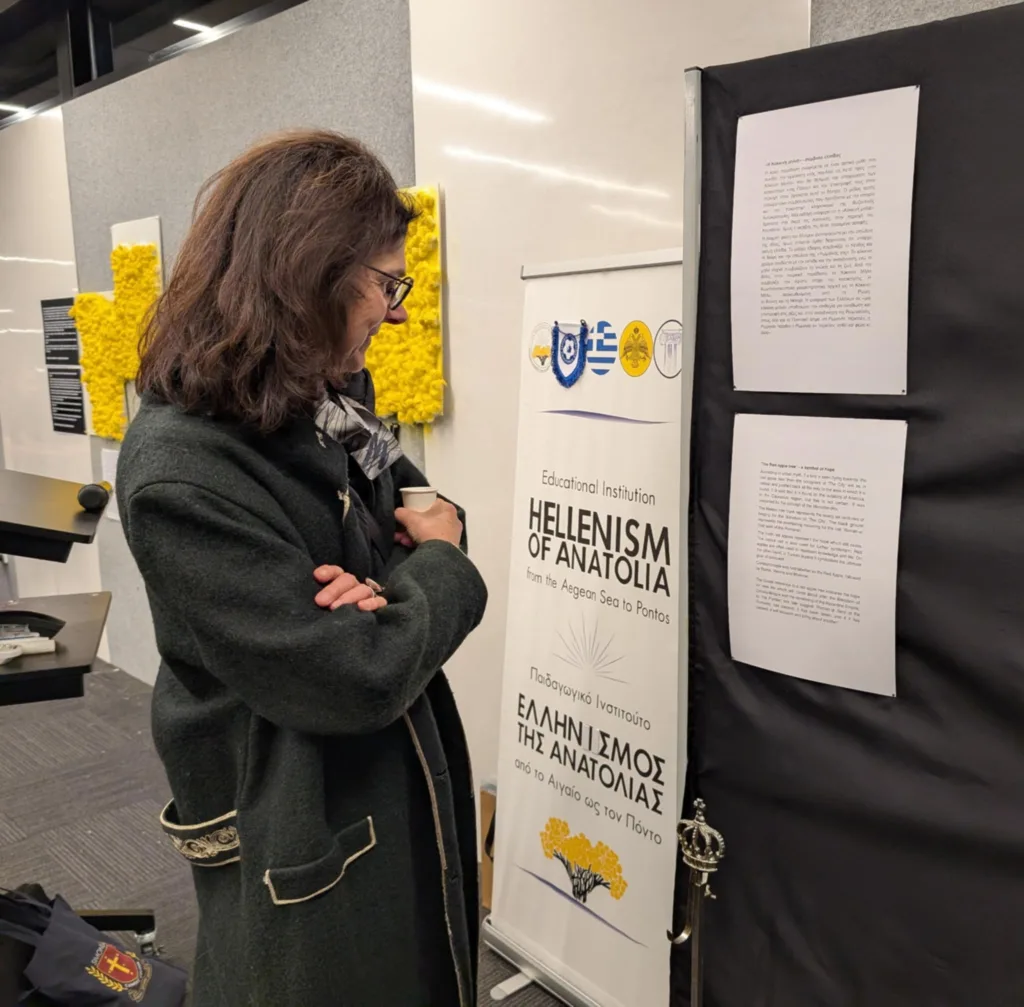

These timeless virtues were present at the ‘Healthy Body, Healthy Mind’ exhibition, which opened on Monday, May 19, at The Lyceum, Alphington Grammar School in Melbourne, Victoria. Held on the anniversary of the Greek Genocide, the event paid tribute to the athletic and cultural legacy of Anatolian Hellenism.

Emcee Simela Stamatopoulos explained that this exhibition is the fourth in a series of events held annually from 19 to 29 May, organised by the Educational Institution Hellenism of Anatolia.

“It isn’t just a day to commemorate,” she said, “but a day of responsibility – the responsibility to pass on historical truth to the next generation. That is also the mission of our institute.”

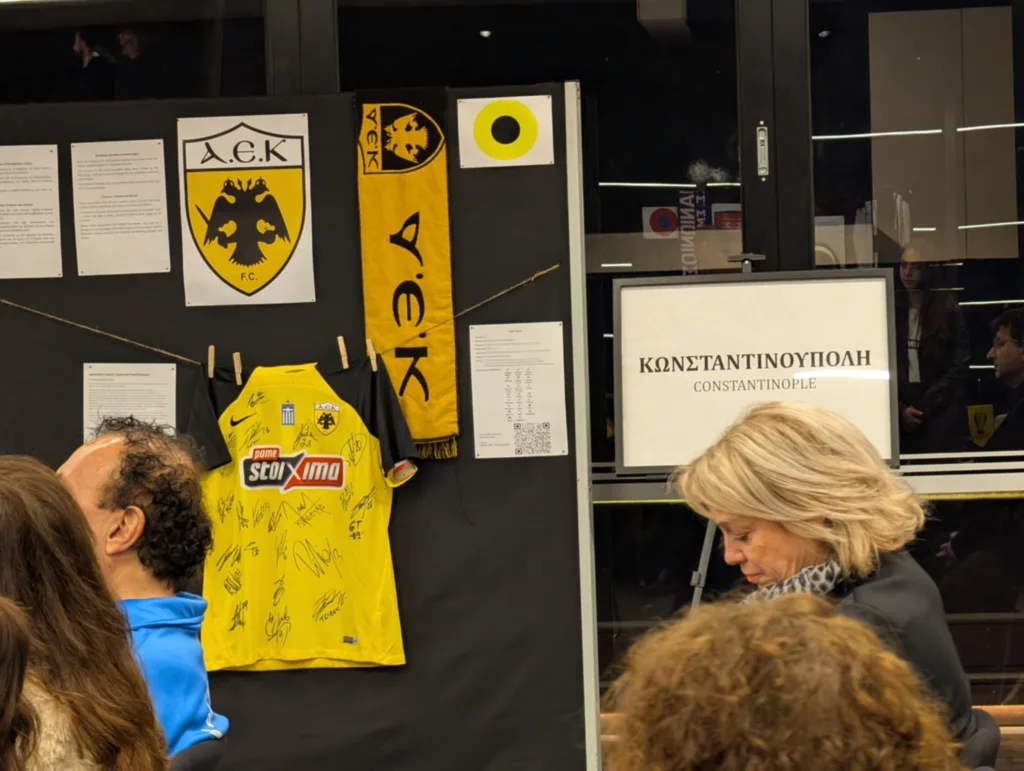

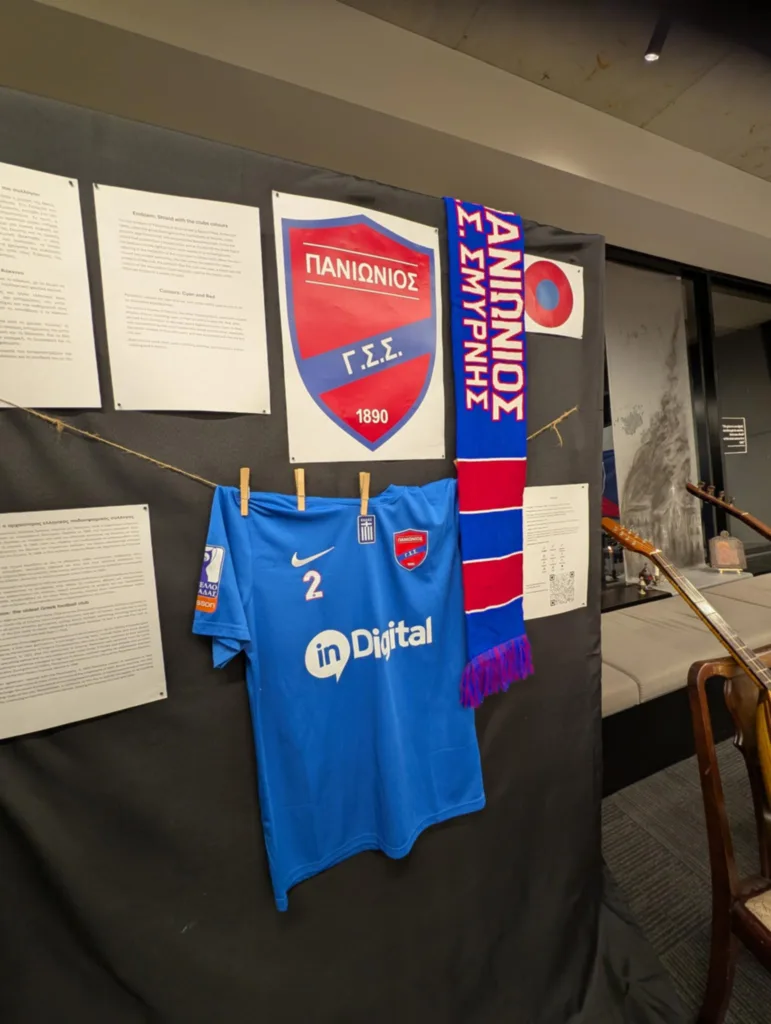

Among the jerseys of PAOK, Panathinaikos, Panionios, Apollon Smyrnis, Apollon Kalamarias, and other historic teams from Constantinople and Asia Minor, flowed powerful stories of resilience, identity, and pride – and even downfall.

Bill Papastergiadis, President of the Greek Community of Melbourne, recalled being offered the chance to purchase Panionios for $3 million. He declined, but reflected: “The way they speak about their culture, their history, their origin – it transcends sport. Sport is just part of their identity. It’s a great way of unifying us.”

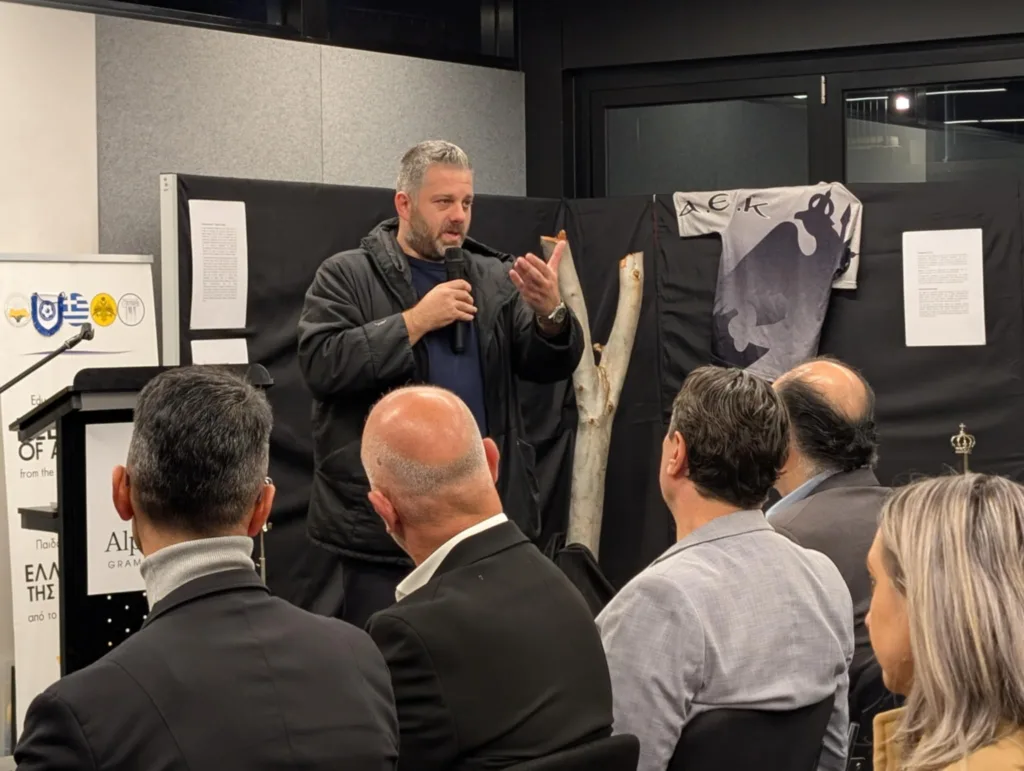

Former soccer player Yiannis (John) Anastasiadis shared heartfelt memories of his time with PAOK.

“We had so much pride in our background. When asked if we were Greek, we always said we were Pontian first,” he said.

“As an 18-year-old in Australia, I had posters of Maradona on my wall. Then I found myself playing against him.”

Author and musician Diogenis Ainatzis, self-taught in music theory and a teacher of the Pontian lyra, spoke from the heart about the cultural erosion faced by Pontian Greeks.

“We brought with us a rich culture, but it wasn’t always recognised. Many of us faced bullying and racism, even though we shared the same blood, religion, and homeland,” he said.

“We are the last generation that still understands the Pontian dialect. With each generation, we risk losing this unique thread of our identity.”

Yiota Stavridou, the exhibition’s coordinator, told The Greek Herald: “These sports clubs were created as cultural hubs for poetry and music. Later, they were brought to mainland Greece by refugees from Asia Minor. Between 1922 and 1940, there were around 40 active sports groups from Asia Minor in Greece.”

Kosta Pataridis, organiser of the exhibition, reflected on its deeper purpose: “Our institute uses these exhibitions to make people think. We want kids to gain a broader understanding of Anatolia. I’ve never set foot there, but I have a deep love for a place I’ve never seen up close.”

“Our obligation is to convey what we know to our children,” Pataridis added.

Last year, more than 800 students visited the exhibition—each one taking a step toward understanding a legacy that must not be forgotten.

*All photos copyright The Greek Herald / Mary Sinanidis.