By George Vardas

According to Greek mythology the goddess Persephone was the daughter of Demeter, the goddess of fertility and harvest, and almighty Zeus. Persephone was hauntingly beautiful and so pure and lovely that, as Stephen Fry has written, the gods took to calling her Kore, which means simply the “maiden”.

But to everyone’s dismay Hades abducted Persephone and carried her off to the dark and gloomy realm of the underworld. Demeter was distraught at her loss although the young goddess would re-emerge for part of the revolving year to be beside her mother and the other immortals.

As the modern American poet Louise Glück wrote in Averno “there are places like this everywhere, places you enter as a young girl from which you never return”.

Demeter and Persephone are often thought of together as the “Two Goddesses” because they were inseparable and symbolised the power of a mother’s love for her only child after she was carried off by Hades.

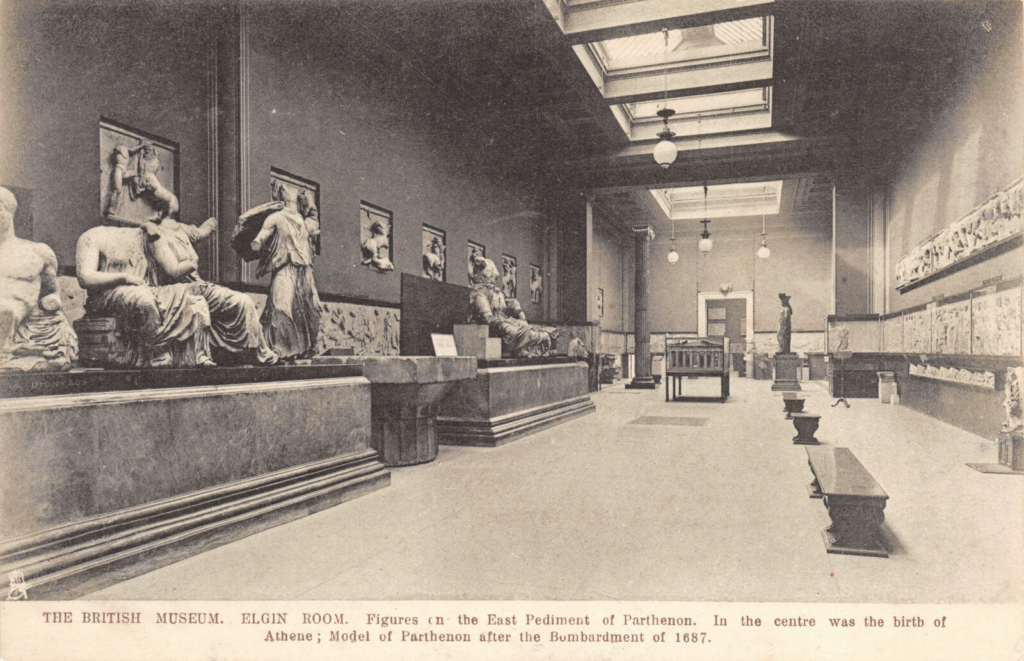

The Ancient Greeks revered their gods in statuary and sculpture and art and Persephone was no exception because of her rare beauty and intensity. The Two Goddesses famously adorned the East Pediment of the Parthenon atop the Acropolis in their “marbl’d immortality” until they were forcibly removed by Lord Elgin and his men, beginning in 1802.

As the bride of the underworld Persephone was often cast in stone and her image used as a grave marker. One such statue dating from the second century BC was recently the subject of legal proceedings involving the British Museum in London.

A sublime three quarter length marble funerary statue depicting a girl wearing a hood and flowing gown, with two snake-like bracelets was illegally excavated in the ancient Greek colony of Cyrenaica (Cyrene) on the Mediterranean coast of present-day Libya – and now a World Heritage site – in the chaos that followed the overthrow of the dictator Gaddafi. It was seized by British authorities at Heathrow airport in 2013 and eventually was placed in the British Museum for safe custody and closer examination pending the outcome of legal proceedings to determine the statue’s true provenance.

The case came before the Westminster Magistrate’s Court in 2015 and evidence was given by a number of experts, including Dr Peter Higgs, curator of Greek sculpture at the Department of Greece and Rome in the British Museum, who opined that the statue was either the goddess Demeter or her daughter Persephone and looked as though it had been excavated in recent years.

Dr Higgs added:

“It is stunning. It is a beautiful, three-quarter-length statue, very well preserved with just a few fingers missing. It is technically brilliant in the way it has been carved, with very sharp details, and the face is very well preserved considering many Greek statues have lost noses.”

The overall consensus appears to be that it is indeed Persephone, depicted as emerging from the underworld.

The Court took the unusual step of hearing part of the case in the British Museum in order to view the statue and hear evidence from experts about its provenance and when it had been excavated. In the end Judge Zani was satisfied that the statue was unlawfully excavated by persons unknown and ruled that the sculpture was owned by the state of Libya and should be forfeited until arrangements were made to return the statue to its rightful owners.

Libya finally took possession of their lost goddess in early May 2021 after formally announcing its repatriation. Dr Higgs was moved to comment:

“It is just lovely to be part of a story which has a happy ending. It will go back to Libya and stand in one of its museums as a star piece, it is a lovely feeling to be part of that.”

In contrast, after reports appeared that the “British Museum Returns Looted Ancient Greek Statue to Libya”, Hannah Boulton, Head of Press and Marketing at the British Museum, was quick to play down any possible linkage (God forbid) with the long-standing case of the Elgin Marbles, declaring:

“This is not a sculpture that is being returned from the British Museum collection; this is part of our work in helping to identify and return illicit trade coming into the UK for potential sale.”

The Director of the British Museum, Dr Hartwig Fischer, also chimed in to point out that an “important part of the museum’s work on cultural heritage involves our close partnership with law enforcement agencies concerned with illicit trafficking”.

That is well and good. The British Museum has properly facilitated the return of a rare cultural artefact which was not part of its permanent collection and so there is no precedent created (unlike the case of the rare Benin Bronze plaques that were sold off as ‘duplicates’ by the British Museum back in the 1950s, but that is another story).

The sad reality remains that the Greek Goddesses Demeter and Persephone, together with the other Parthenon Sculptures, continue to languish in the sterile underworld of the Duveen Gallery in the British Museum more than 200 years after they were carried off by Lord Elgin, totally decontextualised in the museum’s collection.

The day is surely approaching when the Two Goddesses will be returned to Greece – their country of origin – as part of the reunification of all of the known surviving Parthenon Marbles in the purpose-built Acropolis Museum in Athens.

If only a hearing could be held in the Duveen Gallery the stones would surely speak for themselves.

Like their spiritual descendant, Persephone of Cyrenaica, these sculptures deserve to be reunited in their original birthplace to be appreciated in their true context as integral parts of the Parthenon monument.

Only then will there be a happy ending with the Marbles reunited and the Trustees of the British Museum lauded for their valuable contribution to the world’s cultural heritage.

When that day arrives, the abduction of Persephone will have finally been avenged.