By Anastasios M. Tamis*

During the last forty years a lot has happened. Almost two generations passed. In the meantime, Hellenism of Australia underwent its Anacyclosis (the recycling), as the famous Arkas, historian Polybius, used to say. Greek immigrants arrived as young people, almost children, draining their strength and stamina in factories and in the hunt for a decent wage; they set up their households, gave birth to offspring, they themselves sacrificed their well-being and personal quality of life, in order to offer education to their children.

In the 1970s and 1980s they amassed their properties (according to the penultimate Australian Census, at least two and a half houses are allocated to each Greek household, when the average Australian household does not have a single one- 0.9); they consolidated their families, they built clubs and fraternities, they endowed their children with a good education, and they left their grandchildren with fortunes.

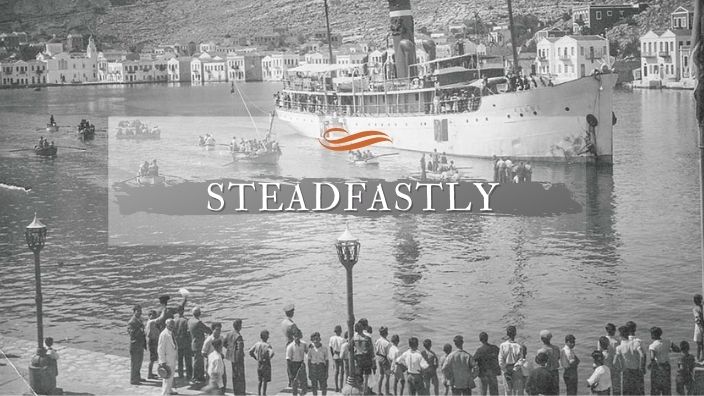

It is true to emphasize that the first generation of immigrants, the agrarian stock and the proletariat of unskilled labourers of the first decades of the post-war period essentially were self-sacrificed. They fell fighting on the altar of hope for a better future for their children. The pioneering Greeks left their ancestral homes, their parents, and siblings to emigrate to Australia, the distant and misunderstood continent at the time.

They said then in the 1950s that in Australia immigrants were eaten by crocodiles and snakes of Far North Queensland, their hands and feet were burned by the sun heat in the vast sugar cane and bananas plantation; they said that in the production lines of factories of this distant land and its smelters the human flesh was just melting; that even the hope for a better future was rotting. They said that whoever departed to settle in Australia, will not return; their emigration was the face of death. It was a living death, a route without tomorrow.

And yet those who dared were eventually saved. Those who immigrated to Australia were eventually rescued from the poverty and misery of post-war Greece. They did not leave their bones in the vast plantations of Queensland, neither in the thankless mines of Western Australia, nor in the factories and foundries of terror. They displayed enormous passion for life and resilience.

The smart ones left Greece, the bold ones, the ones who had “endurance and the grit” in them, those who had a passion and fortitude in them, a load of endurance and vigour. Those who could not capitulate to poverty, scarcity, economic and social condemnation left. Those who wanted to live with dignity, with pride, with nobility of soul, not beggars left in the bosom of their mother that did not have the means to nourish them, to sustain them. Those who left were the superfluous excess, as well as those who have the vision and were inspired to a better life.

In the meantime, the years have flowed. Their children and grandchildren claimed decisively and conquered positions of prestige and influence; they distinguished themselves as professionals, technocrats, politicians, businesspersons, scientists, people of arts, spirits, letters, most of them became teachers.

In the period 1980-2000 the number of students of Greek origin in tertiary institutions, in Australian universities, was the second largest after Asians, and constituted 11.8 % of the total number of students of ethnic background.

The number of teachers of Greek origin in Australia, occupies the second largest percentage after the Italians. According to the latest census, 25% of professionals of Greek origin were teachers. Also, the number of Greeks who have dominated small businesses today is almost the same in percentages as that of the Jews, i.e., 29%.

The Hellenes (Greeks and Cypriots) of Australia conquered Australia socially, economically, politically, and culturally. In Canberra, Australians witnessing the Greek economic wander, conclude: “Canberra was discovered by the British, designed by the Americans, built by the Italians and owned by Greeks…”.

We will try to discuss this course of Hellenism in the socio-economic, cultural and political enhancement; we will attempt to comment on it, to highlight its various manifestations, together with all that it entails in the weeks ahead of us.

From this column, generously offered by the administration of the Greek Herald, we will have our weekly commentary, political, social, cultural, with sincerity and boldness, as I did thirty years ago, when I was still contributing my articles; I come back from my silence, to stand by this struggle for the vindication of the Hellenes, who, during the last seventy years toiled and fought to keep our Greece and its multi-millennium values as an ideology and identity to his children.

*Professor Anastasios M. Tamis taught at Universities in Australia and abroad, was the creator and founding director of the Dardalis Archives of the Hellenic Diaspora and is currently the President of the Australian Institute of Macedonian Studies (AIMS).