Photos and report by Mary Sinanidis.

Australian World War II veterans who fought in Greece have long since passed away, and even their children are reaching an advanced age. Without firsthand accounts, their stories fade into the pages of history books.

Yet, the bonds forged between Greece and Australian soldiers endure, as evidenced when 40 families gathered at the Hellenic RSL to receive the final Greek Campaign Medals awarded to the 17,000 soldiers who bravely served in Greece.

The children and grandchildren of these fallen soldiers shared with The Greek Herald the profound impact the Greek campaign had on their parents, shaping their values and instilling a deep respect for Greece.

At the Hellenic RSL in South Melbourne, they collected their war medals amidst a backdrop of shared war stories, tears, and expressions of their enduring love for Greece, born from sacrifice, camaraderie, and heroism.

Memories linger on:

Andrew Merlo shared that his father, Henry Merlo, volunteered for service on the day enlistments opened, earning the designation of a ‘39er.’

“It wasn’t for king and country,” Andrew clarified. “Unemployment was tough, and he thought he’d go for the adventure. Queuing up alphabetically, he and another volunteer agreed to join the artillery which the other man mentioned was all horse-drawn. They both liked horses and became mates for the next 70 years.”

Once Andrew turned 18, his father finally openly up about his time in Greece.

“It was my idea to take him back to the battlefields in 1994, though my father was reluctant at first, until we started travelling,” Andrew revealed.

“Crete and all of Greece was magnificent. Throughout our journey, we stayed with Greek families who invited us into their homes upon learning that my father fought there. The hospitality was unbelievable.”

At the time, the Russia-Athens pipeline was under construction, making it challenging to visit the Brallos Pass.

“All I had to do was pull out dad’s service papers and they moved multimillion equipment and waved us through,” Andrew explained.

Retracing footsteps:

Recently retired horticulturalist Jeffrey Rowell is embarking on a journey to Greece in the coming months. Armed with his father Norman Rowell’s meticulously documented war logs, he aims to retrace the former soldier’s footsteps during World War II. He will delve into his father’s experiences before he was captured as a prisoner of war in Nafplion, transported by cattle train to Salonica, and eventually sent to Germany as a prisoner of war via Hungary.

“My father documented every piece of information,” Jeffrey shared with The Greek Herald, pointing to logs kept by his father as an invaluable resource.

The same logs helped right a mistake in army records that erroneously indicated Norman’s discharge on January 10, 1940. However, Jeffrey points out his father served as an officer until he retired in 1970.

“When I initially reached out to former Hellenic RSL president Steve Kyritsis regarding my father’s entitlement to this medal, I was told that this was not the case. And so, I had to go to the Australian Archives to set the record straight,” Jeffrey explained.

“My father had continued his military career after the war, following our family tradition. My sister and I were raised as ‘army brats’. This meant that we could do no wrong because we had a father who was an officer. If we did something silly, the enlisted men wouldn’t lag on us. We were the sacred cows.”

He meticulously points to the dates, locations, weather conditions, personal equipment, and other war details recorded in his father’s neat handwriting.

“My dad deserved this medal,” he said.

Learning Greek:

Retired engineer Peter Ford has been to Greece many times since 1996 to retrace his father Frank Ford’s war journey, including once with his father.

“We walked the same land and I found out that he wasn’t lying at all!” Peter said, adding that he had even learnt to speak Greek since that first trip though he complains that he doesn’t practice enough.

“But feel free to call me Panagiotis,” he joked.

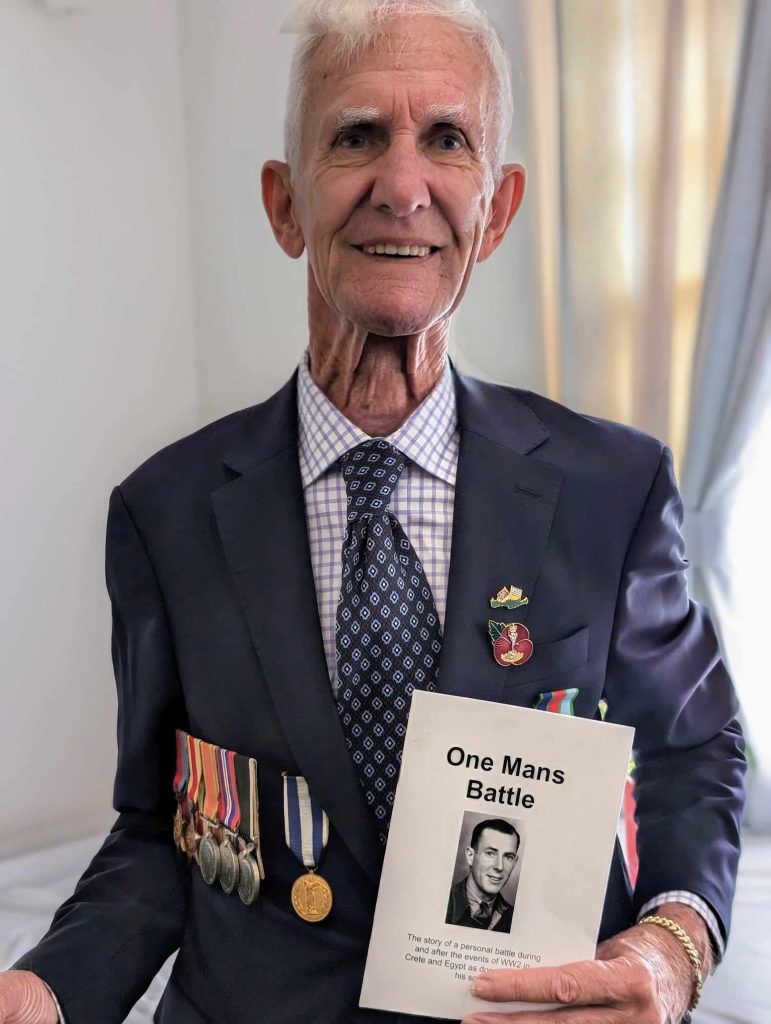

He offers me his booklet, “One Man’s Battle”, written to trace his father’s experiences in Crete and Egypt. A labour of love, Peter has hand-delivered hundreds of these booklets on trips to Greece, shipped them off to the UK and offered them to people around the world. I ask him why.

“Lest we forget!” he said, aware that even in his own family not everyone cares to remember.

Peter urges us to document the stories of veterans and their families.

“Time is running out,” he said. “A lot of history has already been lost. When vets or their families mention something to you, write it down!”

For some families, other people’s writings from the war are all they have.

Greg Spice said he spent a lot of time researching his father’s time at war from other sources because, like many returned servicemen, Sergeant Clifford Robert Spice did not like to talk about his experiences on the battlefield. Instead, Spice found him mentioned three times in Philip Hocking’s “The Long Carry”.

“It is a great honour for the recognition of the service given because it was a defeat, and judged by the allies, there are no medals for defeats,” Greg said.

A family reunion:

Michael Byrne, the son of Private Kevin Byrne, recalls his dad going to the Glen shopping area to seek out Greek men sitting on benches waiting for their wives.

“Of course, he’d chat with them about Greece,” Michael said.

“If he found one from Kalamata, where he fought during World War II, he would call me straight away,” he added, chuckling that his father might as well have been called ‘Byrnopoulos.’

At the Hellenic RSL to receive his late father’s war medal, he is accompanied by his siblings Brian and Annette, their children, grandchildren, even great-grandchildren.

“When we heard Dad would be awarded a medal, we knew we had to come together from Geelong and around Melbourne,” Michael explained.

“It was a good chance for a family reunion, but I hadn’t expected all the little ones to be here in such a formal setting. They were fantastic, though. Brian, my brother, told me his five-year-old grandson clapped at every opportunity.”

His sister, Annette, chimed in, saying the children are all familiar with their grandfather’s history in Greece.

“Michael has written wonderful books about it,” she said, mentioning that their father was involved in the evacuation of soldiers but ended up being left behind along with thousands of others.

Michael added, “He’d tell me stories about how the local Greeks would sneak food into the POW camps, doing everything they could to help prisoners. My father always spoke very positively and appreciatively of the Greek people.”

Private Byrne spent six weeks in Greece before being shipped off to Austria with 6,000 other POWs, later transported to war camps in Germany and Slovenia.

The trauma:

John Barke’s mother Nina Freeman was a nurse in Greece, whereas his father’s unit went to Egypt and Libya.

“They came home from war almost on the same ship and married in Perth in 1943 before having children. It was hard for them, and I believe they were both affected by aspects of war neurosis,” John said.

“If you crouch down behind a sand dune with bombs flying past and machine gun fire, it will affect you.”

He owes the return of his mother to Sir Edward Dunlop who helped extract the nurses from Greece because the English did not intend to.

“Some of them were picked up by a destroyer from Piraeus and they went to Crete and were quickly taken back to Egypt. That was my mother’s story,” he said.

The legacy children:

Some children were not so lucky to grow up with their fathers. Sisters Judith Self and Margaret Davenport lost their father Alfred Edward Lette, who died in action.

“It was six months before my mother found out that our father had died,” Margaret said.

Her sister added, “We still have the telegram with the news that he had died in action.”

Legacy child Sue Foley is happy her son-in-law is Greek and she took Greek language lessons during the pandemic.

“My grandchildren speak Greek and they like to correct me when I make a mistake,” Sue said.

For her, Greekness is a connection to her dad Alan Pitts who was in Crete, Northern Africa and New Guinea. She lost him when she was four, and though he came back from war his death was attributed to his war service.

“This medal is special,” she said, adding that it was yet another connection with a man she barely got to know and vaguely remembers.

“I can only remember that he was very quick in his movements and would leave a wooshing as he passed. I remember having a green stick fracture and my father cutting it up.”

Following his death, Sue’s mother was left with three children.

“There were three of us under the age of six, and this was not easy for our mother,” she said.

Even more stories were shared as children collected medals for their parents.

For Steve Kyritsis, former president of the Hellenic RSL and former Vietnam veteran, it was the end of a circle that began a few years ago following meetings with former Greek Consul General to Melbourne, Christina Simantiraki. Since then, Steve and his team have scoured war records, newspaper clippings and social media.

“There were a few hiccups along the way, but the end result is perfect,” Steve said, happy that the medals are now where they belong.

Greek Consul General of Melbourne Emmanuel Kakavelakis said, “It is a moral duty of my country to recognise every last veteran who fought so far away from his motherland. It is also an opportunity to celebrate and reflect upon the relationships between Australia and Greece, especially the relationship and alliance that was fought mainly in the trenches of warfare.”

A soldier himself, Colonel Ioannis Fasianos said, “It took some time for Greece to find them, but it finally happened.”

Mr Kyritsis said that there are at least another 60 families out there who have yet to receive their medals. And for them, he will not stop.

*All photos copyright The Greek Herald / Mary Sinanidis.