The migrant story is one that resonates with everyone in the Greek community at one point of history, especially with most of our grandparents and great-grandparents making their way over by boat in the 50s, 60s and 70s.

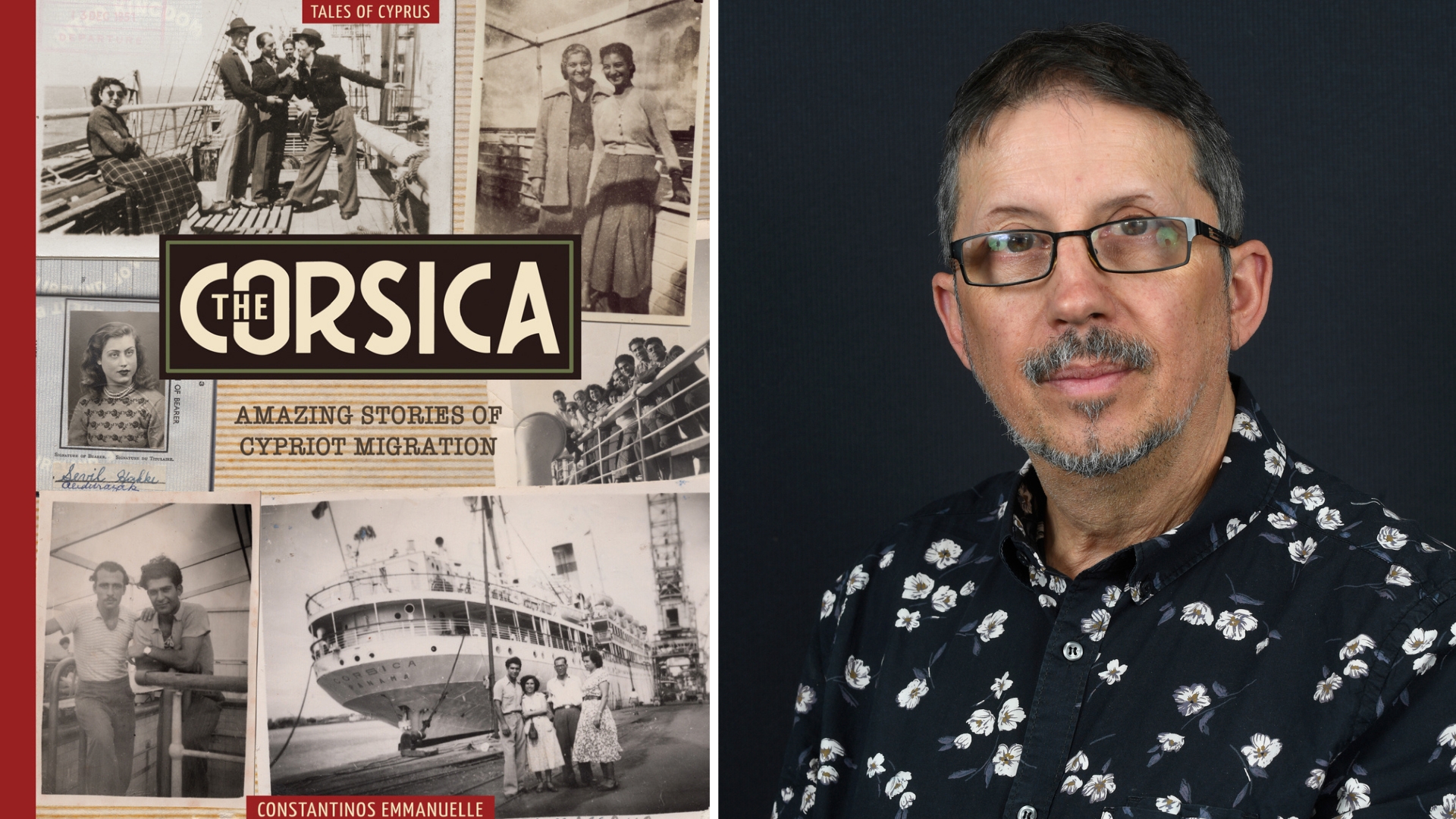

While for many families the migration journey started on the famous ship Patris, there is a less known journey, starting in Cyprus, that Con Emmanuelle is shedding light on with his new book ‘The Corsica’.

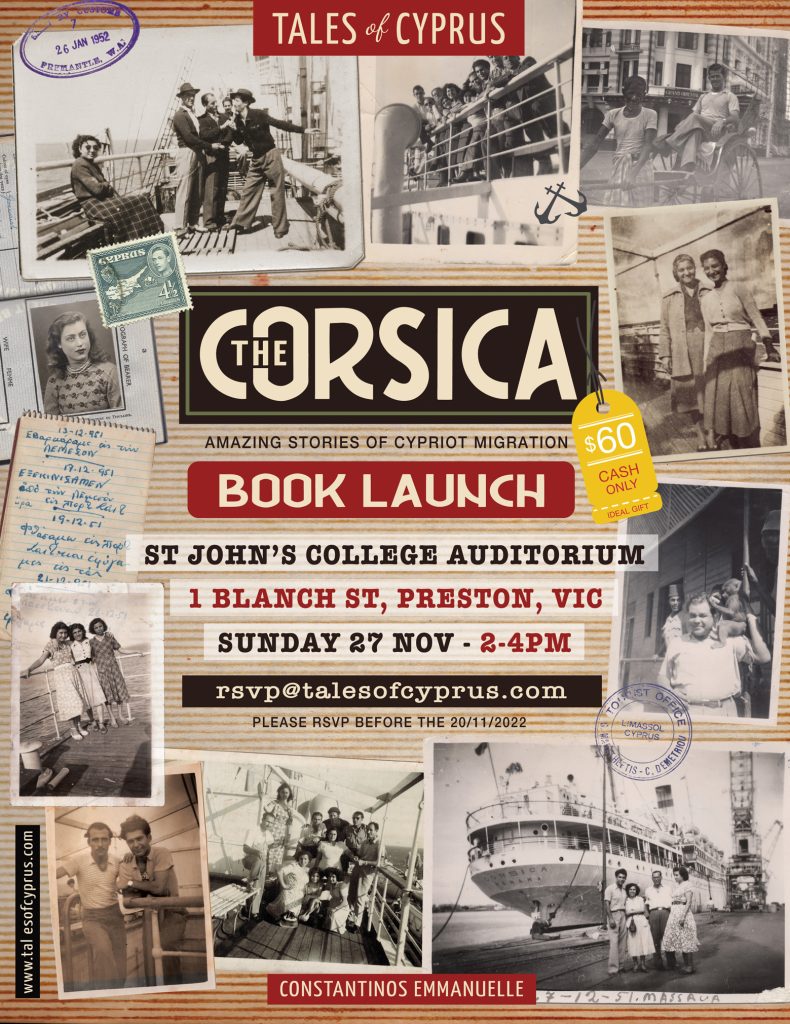

Ahead of the launch of his book, at Melbourne’s St John’s College Auditorium on Sunday November 27, we talked with Con about the process of collating the stories and photos he gathered from members of the community to form a piece of history for generations to come.

Tell us about your new book.

This is my second self-published book for Tales of Cyprus. My first book ‘A Tribute to a Bygone Era’ focused on life in Cyprus during the British Era, whereas this book looks at Cypriot migration after the Second World War and more specifically, the fateful voyage of a group of brave Cypriot migrants who travelled to Australia on board a dilapidated old ship called the Corsica.

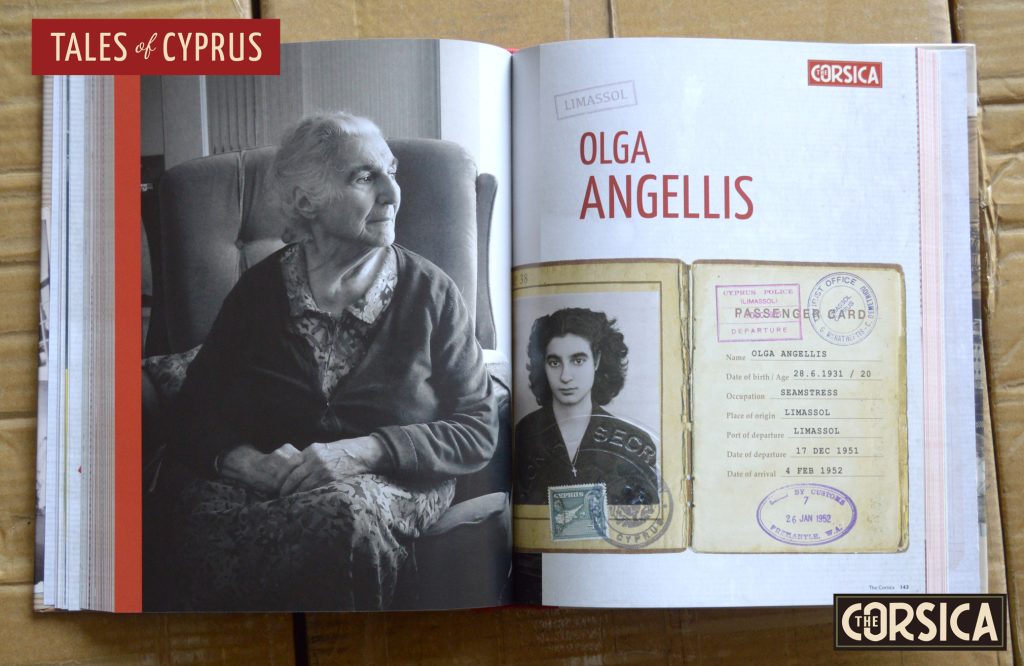

The Corsica only made one trip from Cyprus. It left in December 1951 and arrived to Melbourne in February 1952. In total, I have managed to track down seventy-eight passengers who travelled to Australia on the Corsica, of which, fifty-six where selected for this book.

Why have you chosen to focus on the journey of the Corsica?

During the course of my many interviews for Tales of Cyprus over the last ten years, the name of a ship called the Corsica kept popping up. I soon discovered that this was no ordinary migrant ship and no ordinary migrant journey. In fact, no other ship or migrant journey seemed to stir up as much emotion as the Corsica. ‘It was the ship from hell,’ as one person described it.

I was intrigued and fascinated by what people were telling me – I wanted to investigate why the Corsica was regarded as one of the worst migrant voyages from Cyprus. I soon discovered that the Corsica contained the largest group of Cypriot migrants to ever leave the island at the one time. Of the 863 passengers on board the ship, 784 (or 91 percent) were from Cyprus.

What was the writing process like with this new book?

As always, I prefer to meet with my interviewees in person – face to face. When the pandemic occurred at the start of 2020 and Australia went into lockdown, I had to conduct some interviews by Zoom or by phone. For the Greek Cypriots passengers, I would conduct the interview in Greek, recording it with video or audio, or both.

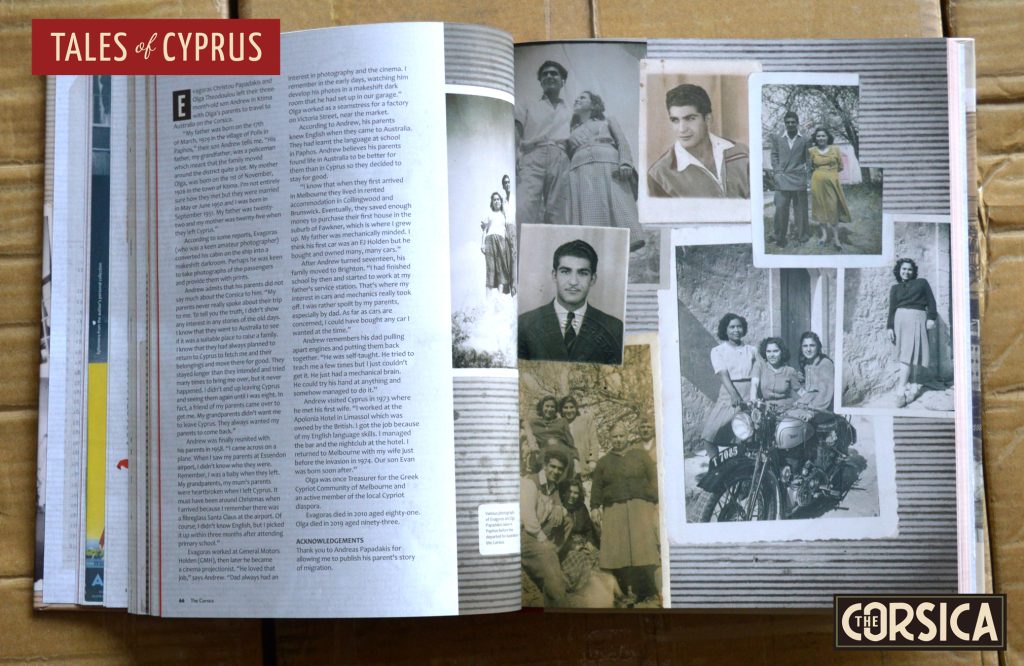

After the interview comes the process of translating what is said into English and creating the text articles for the book. Apart from the written text and the documented living memories, I also took time to scan any old original family photographs from that period. To that end, I am proud to say that the book has over 400 beautiful vintage photographs.

To be honest, I am extremely fortunate to have graphic design experience. My design skills have allowed me to create the book myself – from cover to cover, text graphics, images, everything. In fact, Tales of Cyprus would not be possible without my design ability and the power of social media.

Your book showcases many personal migration stories. Do you have a favourite and why?

Not really a favourite – but there are a few that tugged at my heart strings. One passenger named Stavros described how his dear mother couldn’t bring herself to say good bye or to tell him how she felt by his decision to leave Cyprus to go to Australia – so instead – she managed to secretly write down her thoughts in a notepad which she hid inside his suitcase.

He did not discover the letter until after he arrived and was unpacking his suitcase. Needless to say, he became very emotional as he read the letter to me during the interview.

Why do you think it’s so important to share these stories and capture the history of Greek migration to Australia?

Well first and foremost, to record, document and preserve the living memories of this extraordinary generation of Cypriots. If not, their stories go to the grave and are lost forever. My mission has always been to document as much as possible so we have a shared history to fall back on – to appreciate – and pass on to future generations. I think it’s important to reconnect to our roots and to pay our respects to past generations and to honour what our parents and grandparents achieved. It’s important to acknowledge the truth – that their lives mattered – or that THEY mattered.

Is there anything else you would like to say?

I think what has been most humbling for me as the son of Cypriot migrants, is just how tough and resilient my parents’ generation really was. I mean, think about it. Who boards a ship to leave their village and family? Who leaves their homeland with barely a shilling to their name and with no knowledge of English to speak of – only to venture into the unknown and travel to the other side of the world to a foreign country in search of a better life? Who does that? It’s unbelievable. I am in constant awe of this generation of Cypriots. They are (and always will be) my heroes. We owe them such a debt of gratitude. We really do.