Nearly 3000 pavers engraved with names of people and their respective origin make up the Settlement Square in South Australia’s Migration Museum.

Among those are many Greeks who made the state their home as early as the 1830s.

The Square is a memorial for families to remember their ancestors’ arrival in Australia and value the stories that create South Australia’s multicultural tapestry.

“Stories of migration are key to understanding both the history of South Australia and to social cohesion in the present,” Museum Director, Mandy Paul told The Greek Herald.

“Stories of individuals and families collectively tell the story of our state. Understanding our past helps us to build a future where cultural diversity continues to be valued and celebrated.”

Acknowledging the past to lead for the future

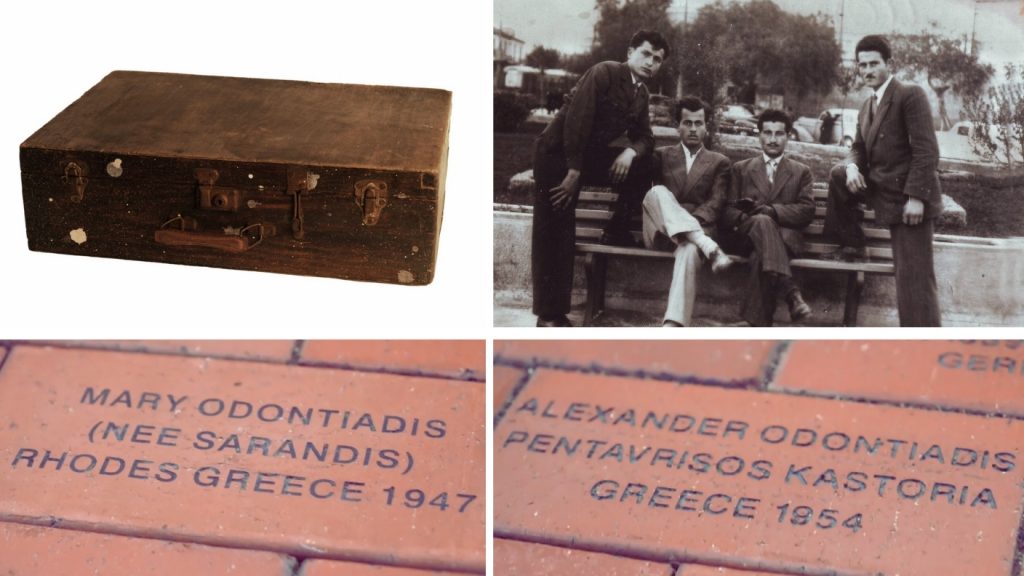

On two pavers that lie close to each other are the names Alexander (Alex) Odontiadis from Kastoria and Mary Odontiadis (nee Sarandis) from Rhodes.

The paver dedicated to Mary Odontiadis was placed in the Settlement Square only a few years ago as a gesture of honour from her four children Tammy, Angela, John and Michael.

“When the museum launched the paver campaign -twenty years ago- mum took the initiative to dedicate a paver to dad. Later on, she also donated the small wooden suitcase dad had with him on the journey,” said Michael.

“When mum got sick, we thought to honour her by doing what she had done for dad. By coincidence the pavers are close to each other.”

“Our parents sacrificed a lot and they were very humble in how they lived their lives. This a way of acknowledging the contributions they’ve made to society,” Michael said as together with his sister, Angela, they started unfolding their parents’ stories.

Two pavers, two stories, one life

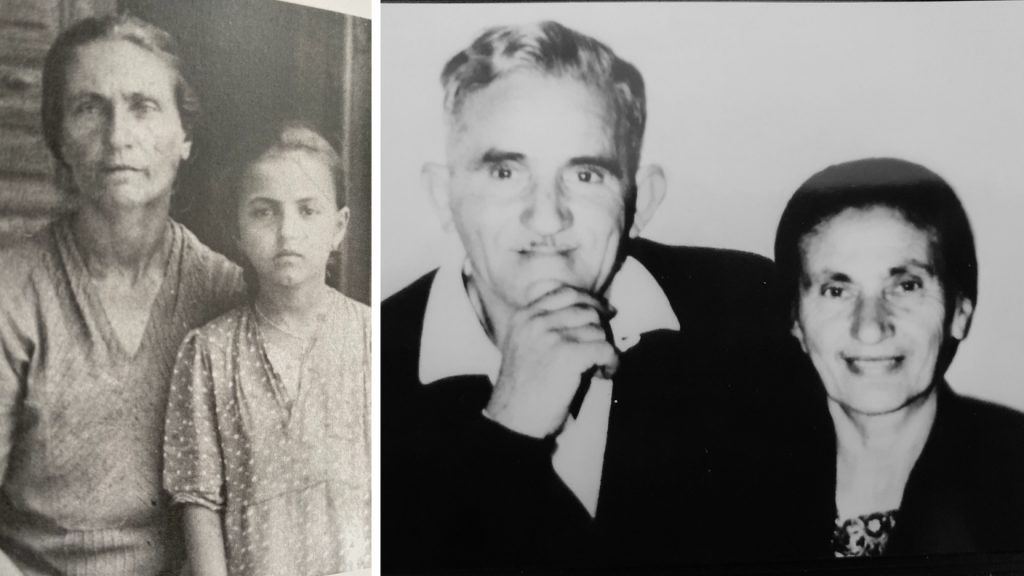

Born in Rhodes in 1939, at the beginning of World War II to parents who had endured the atrocities of the Ottomans in Asia Minor, Mary experienced loss, hunger and hardship during the first tender years of her life.

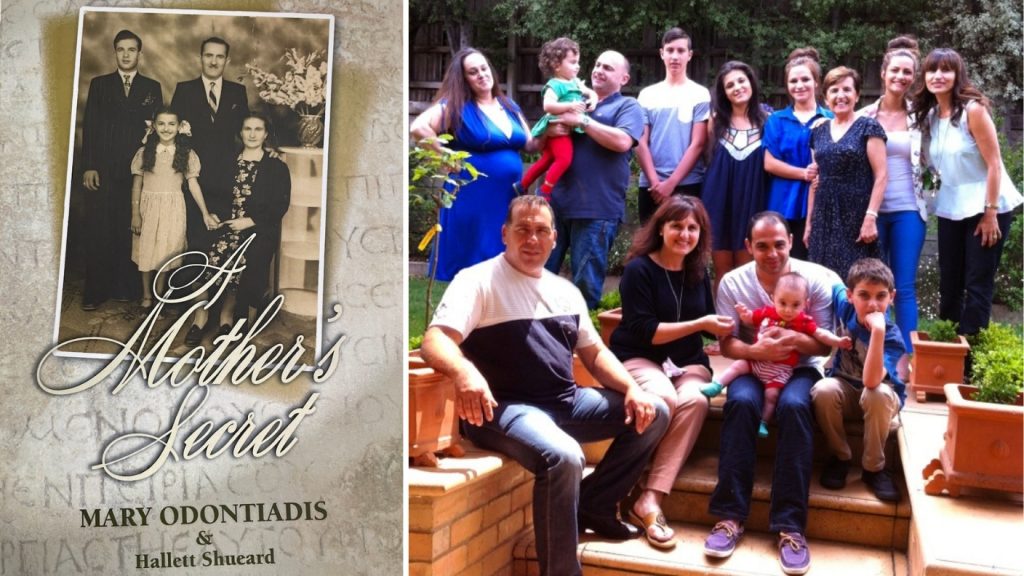

“I can vividly remember the bombs falling and running to the shelters when the sirens started. My mother, Evangelia, used to put me on her back and cover me with a blanket because I did not want to look,” reads a part of the memoir Mary Odontiadis wrote in 2008, entitled A Mother’s Secret.

“She, used to tell me that when I was born, she did not have enough milk to feed me, and so she used to give me to another woman to breastfeed me…We managed to survive the war despite there being little food available,” reads another part.

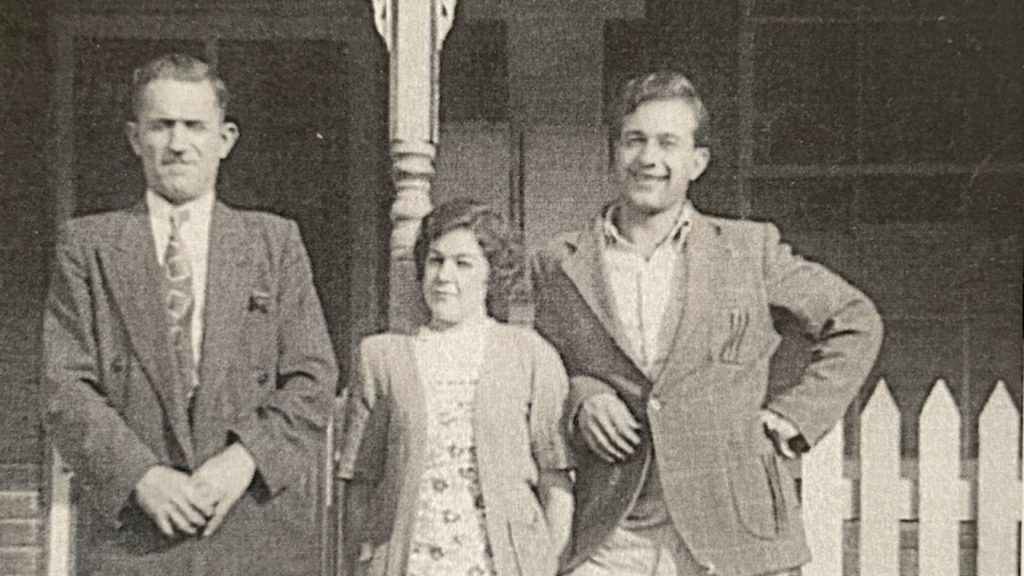

In 1947, 8-year-old Mary immigrated to Australia with her mother via Port Said aboard an Egyptian cargo ship named ‘St Misa’. Her father and older brother, Kostas (Con), were already in Australia hosted by relatives who had immigrated in the 1920s.

Shortly after their arrival, the family purchased their first home at Gouger Street and Mary was attending primary school in the morning and in the afternoon the Greek lessons organised by the Greek Orthodox Community of SA.

When she was 15, she met newly arrived migrant from Kastoria, Alex Odontiadis, who lived at the family’s Couger street house as a boarder.

He was only 20 years old and came out to Australia in 1954 on the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration (ICEM) – currently IOM- assisted passage scheme. He was contracted to work for the government for two years.

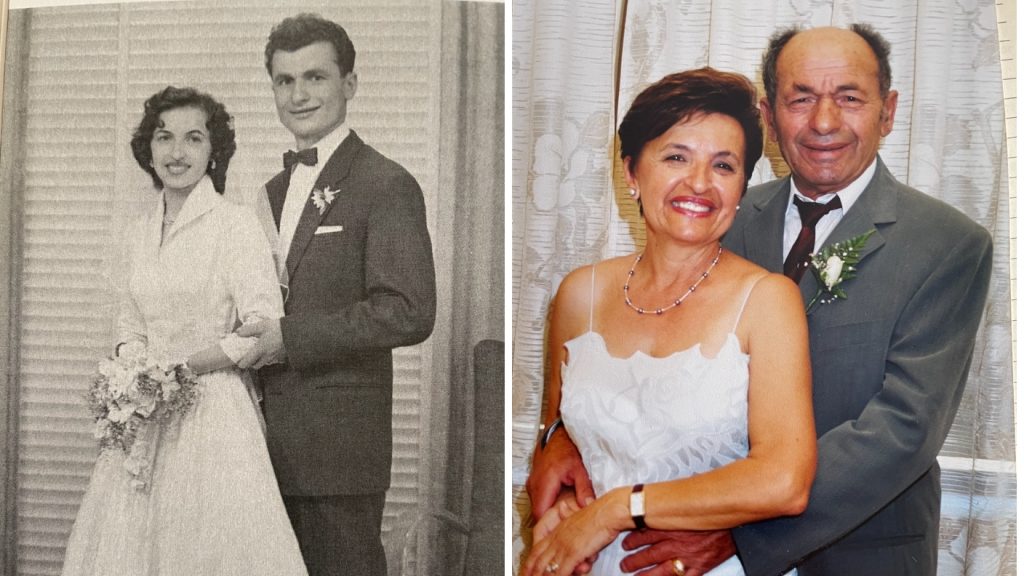

The couple got engaged in 1954 and ended up getting married in January of 1956, after Mary’s parents found out that Alex had kissed their daughter on the cheek during a party.

Soon after the marriage, their family started growing.

Growing up Greek in Australia

“We had a good upbringing. There was a good balance between mum and dad. Mum was a very proud Greek person and very stoic in her language, history, tradition but very Westernised in many respects,” said Angela.

“What defined her as a person was when in her 40s, she started her own career. She wasn’t the housewife any longer but the independent and respected member in her community and we admired her for that. She was determined.”

“Dad was very different but had his own impact and legacy. When he came to Australia, he was afraid not to lose his culture and for this reason he became an integral part of the Pontian Brotherhood in South Australia,” Michael said.

“He was in charge of organising the first youth dance group of the Brotherhood that we all joined. Being Pontian, and feeling that culture was in our blood from a young age.”

“We were forced to go to Greek school growing up, something we are glad for and appreciated later on in life,” said Michael.

“We are proud for both our parents and what they achieved but we are most proud of our mother for the way she reacted when in her early 70s, after all the hardship she had gone through she accidentally found out she was adopted,” agree Michael and Angela.

Mary Odontiadis died aged 81 without knowing who her biological mother was. The family members who knew and had sworn not to reveal the secret had also passed on.

The last few lines in her book give some closure to a story that is sure to be remembered for generations to come.

“…When I look at my family today, I cannot begin to express enough how fortunate I was to have such a lovely woman for a mother. For her to raise me as her own daughter, to give me love and guidance, to teach me to be humble and to forgive any wrongs that I and my family have suffered, I am so thankful for…”

*Selected stories from the South Australian Migration Museum’s Settlement Square will be featured in the ‘Paving the Way’ exhibition, open until 28 February 2022

*The book ‘A Mother’s Secret’ by Mary Odontiadis and Hallett Shueard can be found here