By Dr Spyridon Mouratidis*

During the Second World War, Greek art was used to depict in colours and to deliver in perpetuity the conflict of the Greeks with the Italians, a conflict that ended in triumph for the Greek people.

From the first moment, art depicted vividly the general excitement and the overwhelming enthusiasm of the Greeks, the war momentum and the greatness of the victory, but also the trials, the hardship and the moaning of the wounded, even death – the whole spectrum of war.

Conscripted in the war against the Italians were cartoonists who worked for newspapers at the time. From the first moment of the declaration of war, the cartoonists were “at work.” Their presence was felt with cartoons mainly, but also with posters and some comics. The newspapers that keep regular cartoonists, made proper use of them. Others created special columns and accepted free collaborations or hired cartoonists on purpose.

From the beginning of the war and until the invasion of the Germans into Greece, the Greek cartoon, free from the heavy burden of the unbearable censorship of previous years, reached its highest peak.

The first people that “entertained” the civilian population on a daily basis, as well as the soldiers at the front, were the eminent cartoonists of the time: F. Demetriades, C. Gayvelis, St. Polenakis, An. Vlassopoulos, Sofoklis, Antoniadis, An. Vottis, P. Pavlidis, K. Bezos, N. Castanakis, and Mich. Nikolinakos, followed by a chorus of younger cartoonists.

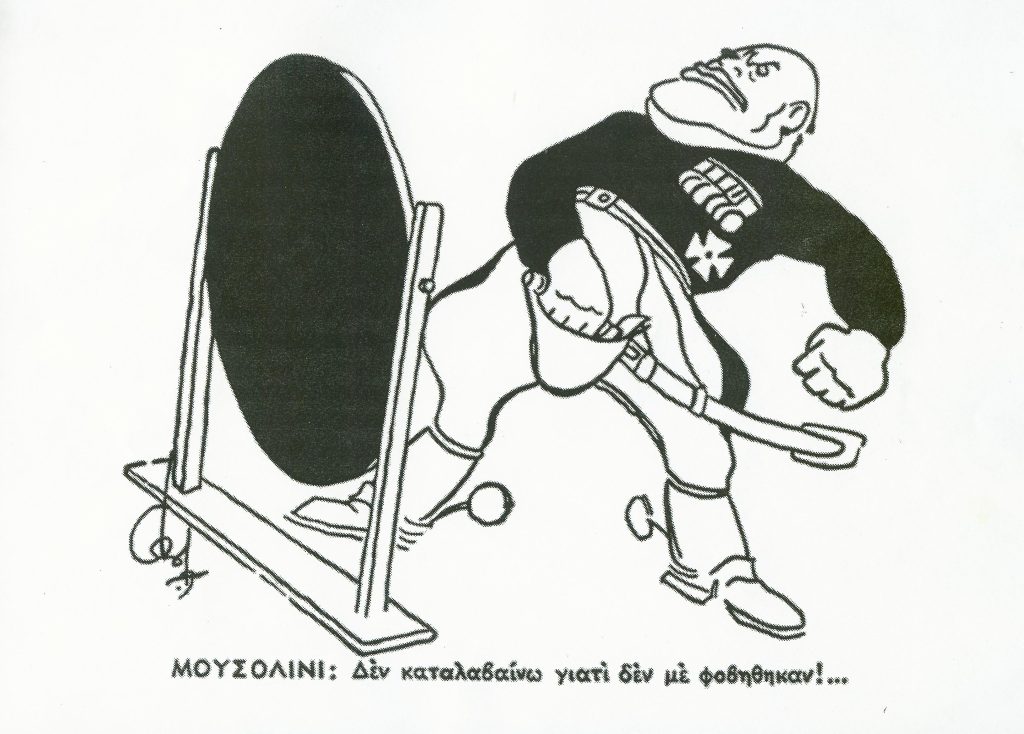

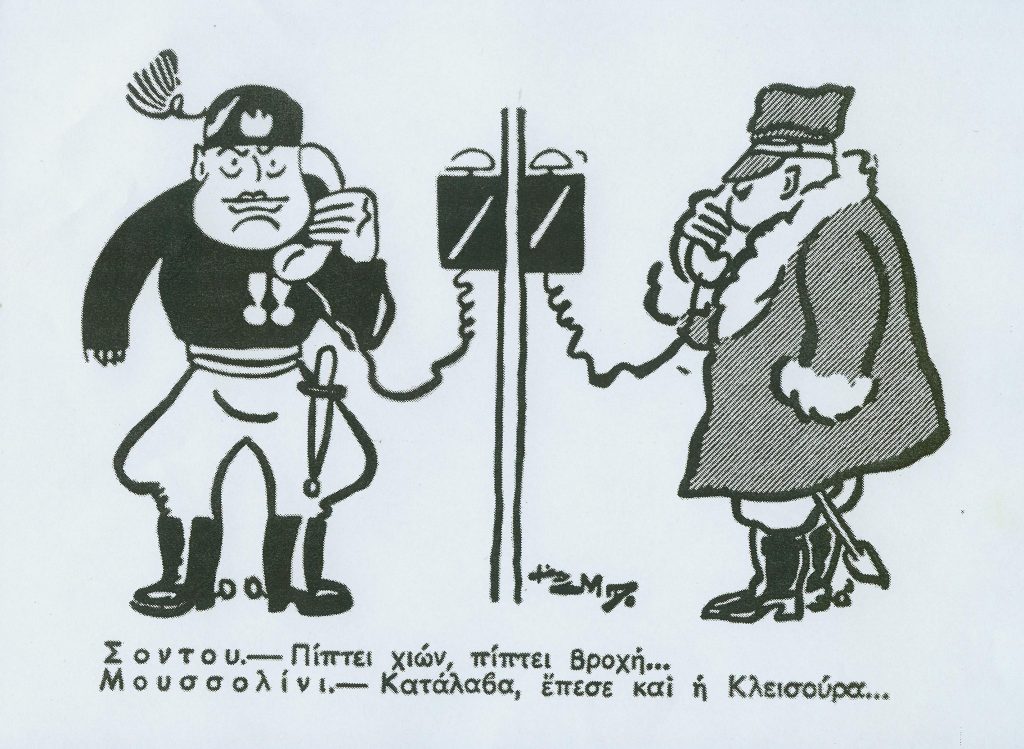

The language of the cartoons was adapted to that of the time, sometimes purist, sometimes not, in order to serve the intended purpose: to ridicule the invader. The truth is that the Italian leadership itself was giving reasons to ridicule the war, with Mussolini first and best. Mussolini was a fat, bald, shorn dictator, with pompous gestures and expressions.

The attack on Greece had been decided on 15 October, at a meeting in which, besides Mussolini and Ciano, the chief of the Italian Army General Staff and other military and political officials took part. The military, in spite of their serious misgivings, undertook to prepare the attack at the time appointed by the Italian dictator. The limited forces that took part in the initial phase of the attack, as well as the objectives and direction of the attack, testify to the expectations of the Italians, which proved impossible.

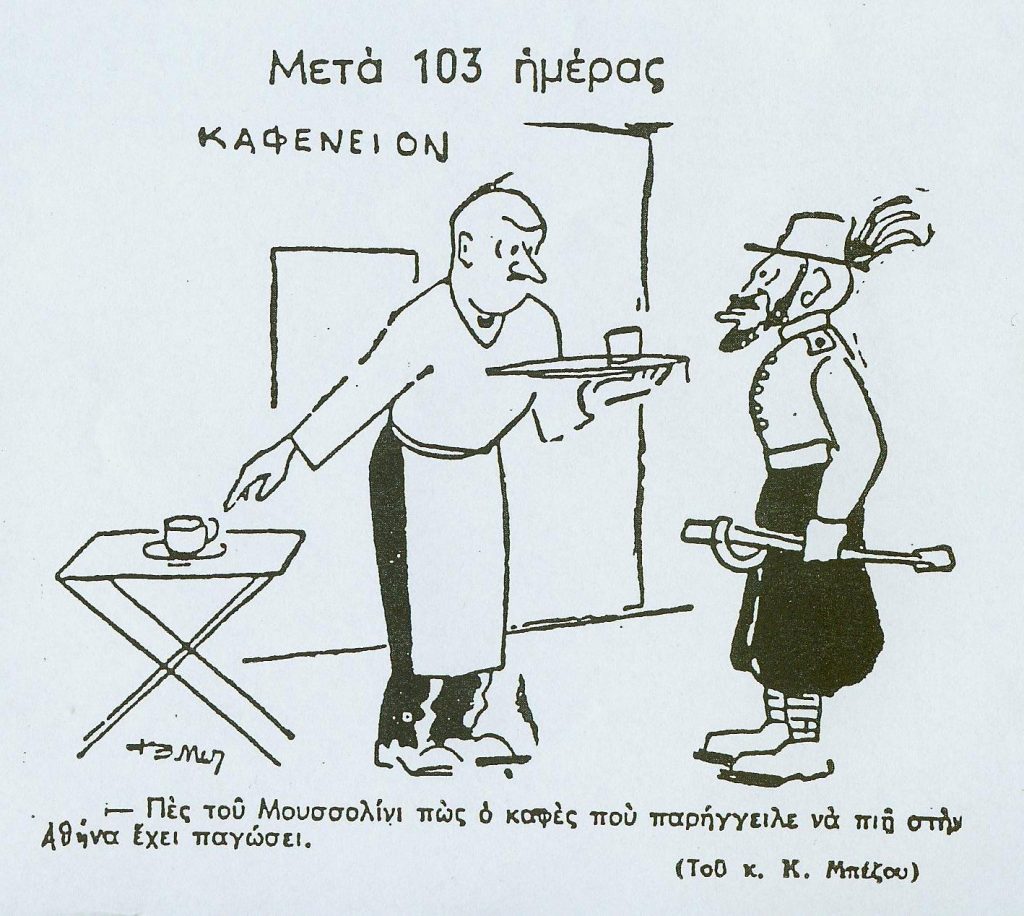

Mussolini had referred to “a coffee walk to Athens in five days.” Cartoonist K. Bezos sketches the Greek waiter saying to the Italian, “tell Mussolini that the coffee he ordered to drink in Athens is frozen,” since, in the meantime, not five but 103 days had passed.

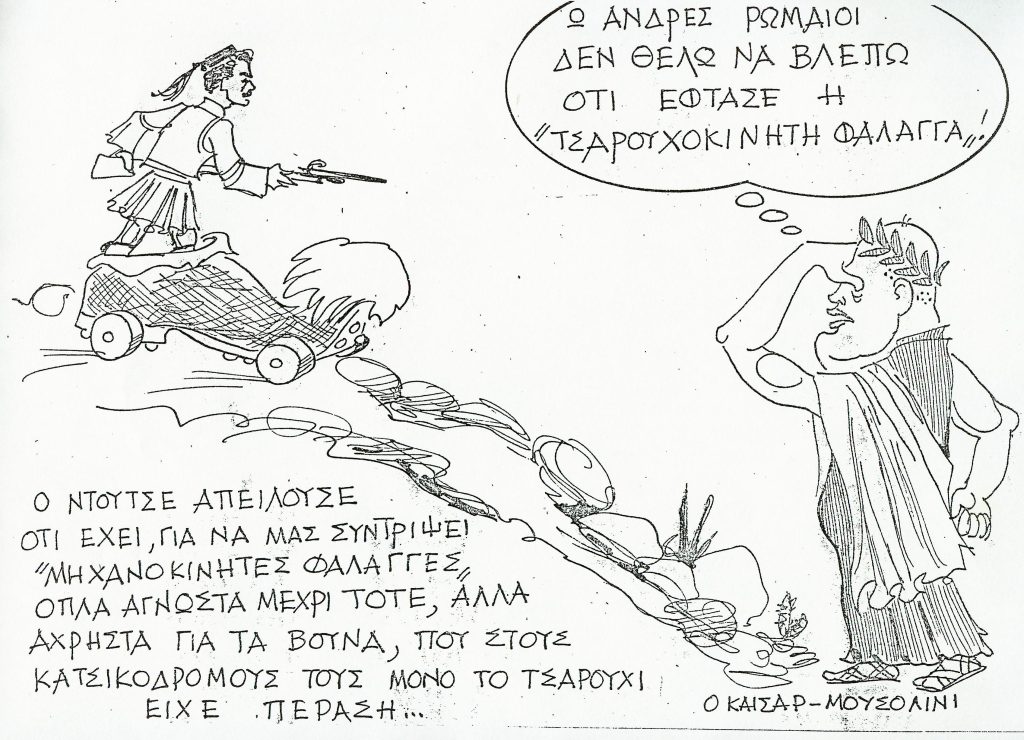

Mussolini threatened that with his mechanised phalanges he would crush all resistance, but reality miserably refuted him.

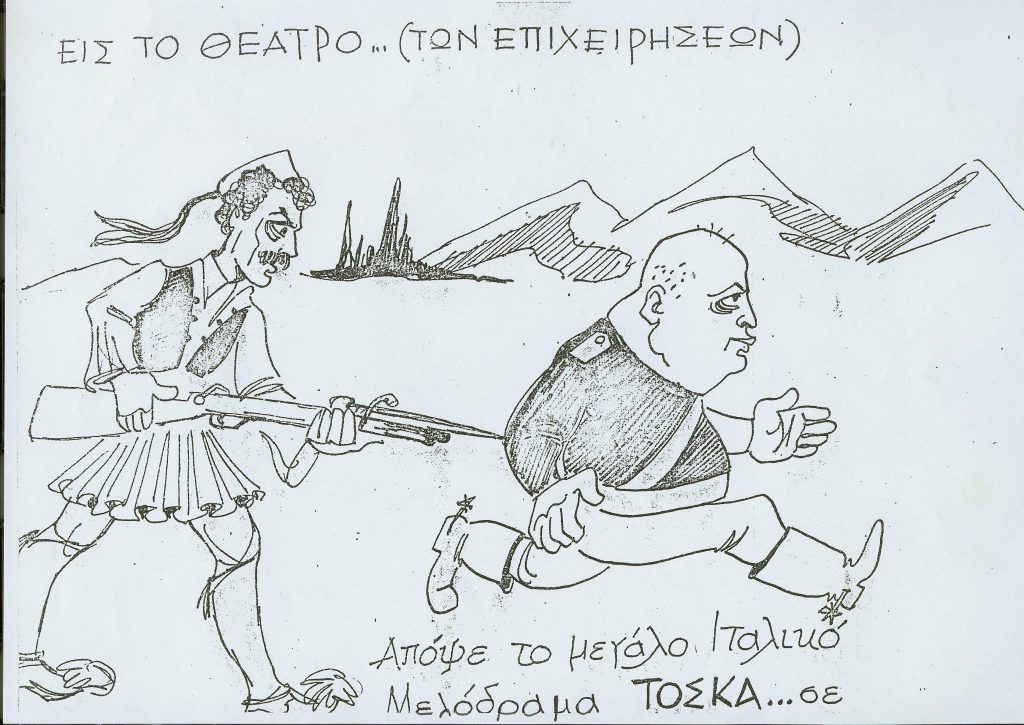

On November 14, the Greek counterattack on the front began. The Italians retreated, war booty was plentiful, Italians were captured. Soph. Antoniadis makes excellent use of his pen, describing to us what happens in the theatre… of business.

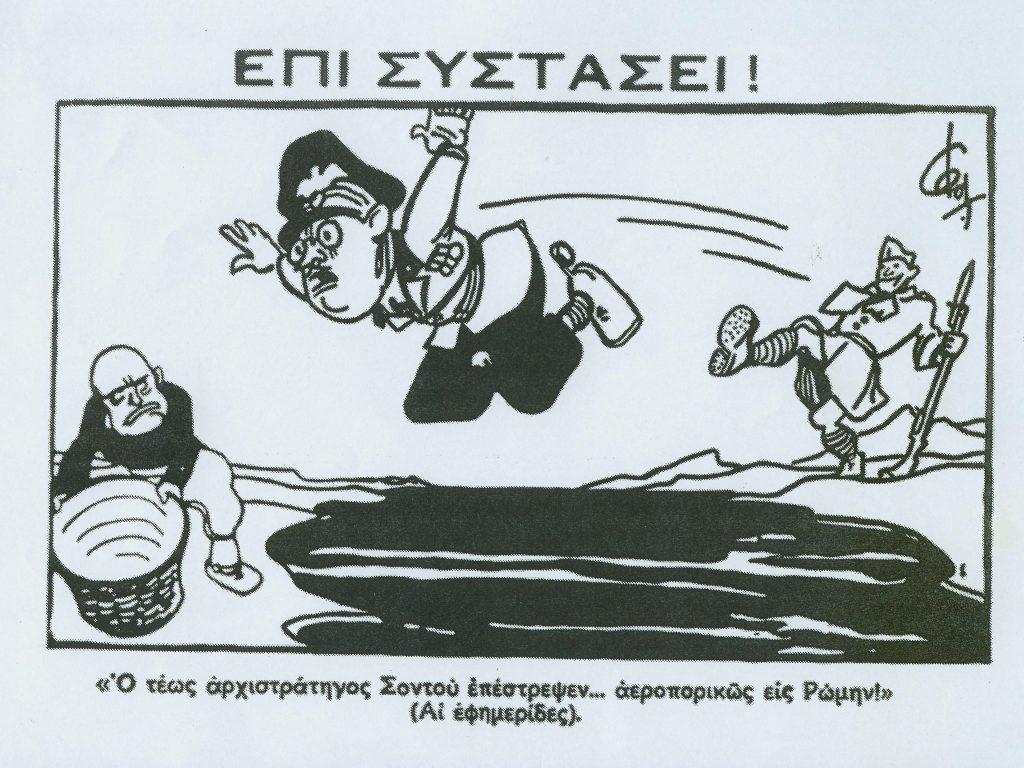

The Greek victories had, of course, a serious impact on the opponent’s camp. From mid-November, a crisis broke out within the Italian leadership, leading, at the end of the month, to the resignations of generals and the recall of others from the front.

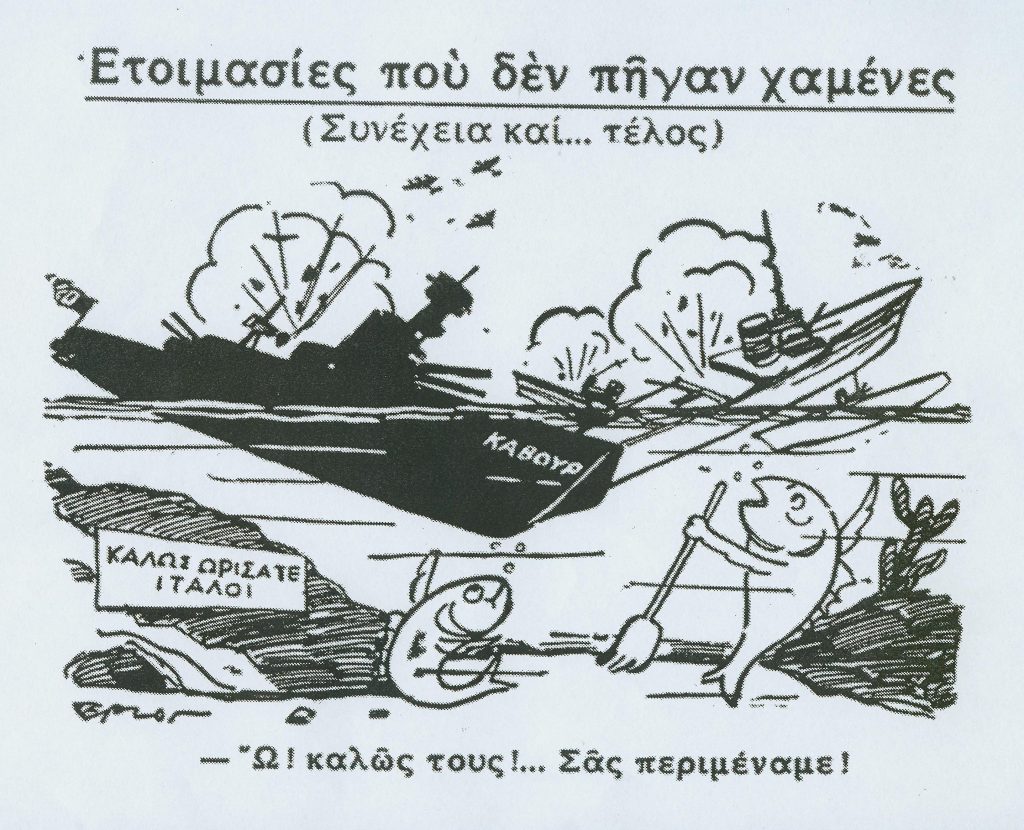

During the same period, the Greek navy had to show remarkable action. The losses of the powerful Italian fleet were great.

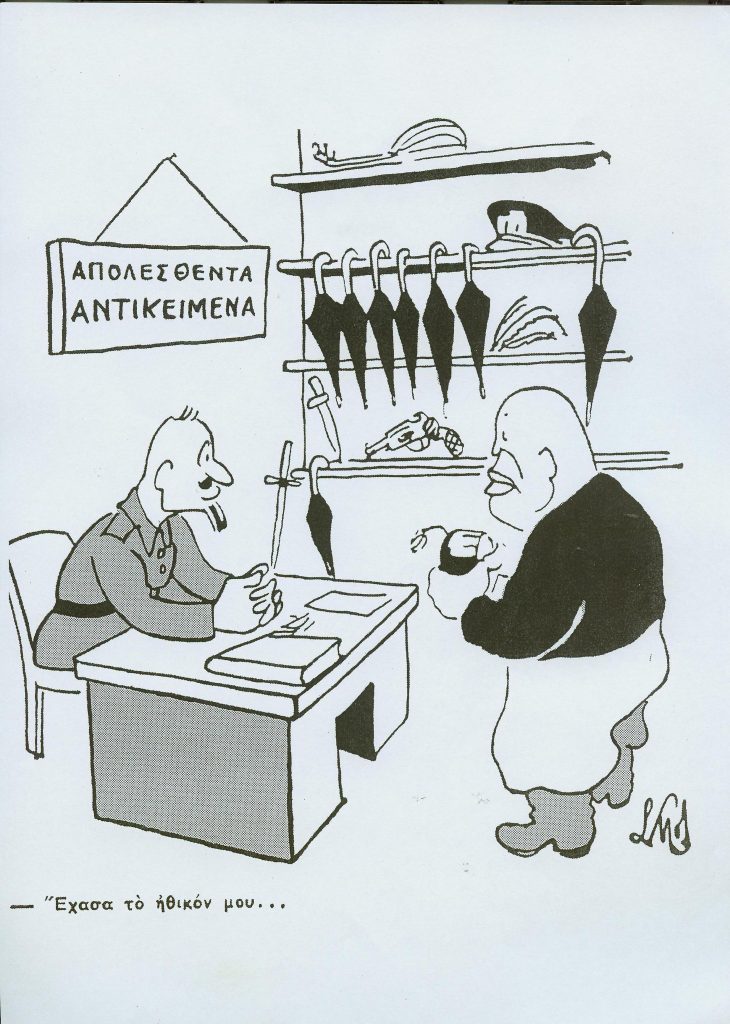

Despite considerable losses and hardships from the heavy winter, the morale of the Greeks was very high in contrast to that of the Italians.

The Italian divisions, alternating at the front, had female names (“Julia”, “Ferrara”) or funny (“Tuscan Wolves”) and this was something that did not go unnoticed by war cartoonists.

One of the main causes that led to the explosion in cartoons was the war communiques that tried to justify the debacles on the war front.

Mussolini believed in the spring offensive of March, but it found the Greek army with the same high morale as it had in the previous year’s operations.

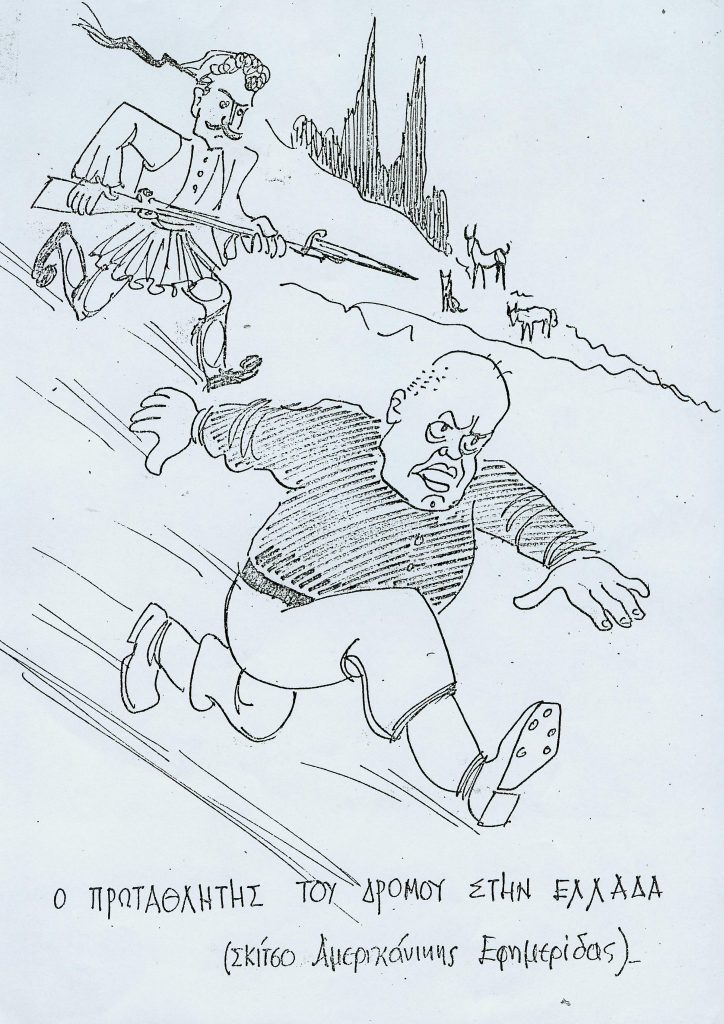

Many of the sharp sketches of the Greek cartoonists were reprinted and sent to Europe in the form of postcards. Foreign cartoonists also dealt with the Greek campaign. For all English cartoonists of the period 1940-41, the illustration of the Greek resistance against the Axis had mainly one thing in common: the connection with the ancient ancestors.

In Mussolini’s face, the cartoonists ridiculed fascism: sweaty from aimless hunting in the Greek mountains, dressed as a thief or transformed into a pig, a cowardly jailer under Hitler’s orders, etc. Cartoons were also published in American newspapers.

The battle of the artistic media in the war of the ’40s had an absolute anti-fascist character. There is little to suggest a quarrel between the Greek and Italian people. The focus is mainly on the supercilious Mussolini, the defeated generals and the fallen Versailles and carabinieri.

The reductive descriptions of Italian warriors put forward during the war, justified at the time because they served specific expedients, did not correspond to reality. At the front, Italian soldiers, like their opponents, paid the price of an unjust war, drenched in mud and snow. They fought as bravely as their opponents, and stubbornly claimed every hill and strait in the inhospitable Albanian mountains. But they succumbed because their opponents possessed, beyond bravery, faith in the justness of their cause.

Bibliography:

– Cartoon Friends Association Archive.

– K. Liontis, “Visual Arts and Epic of the ’40s”, Kathimerini newspaper, 26-10-1997.

– C. Panayiotou, “Mocking Fascism”, Kathimerini newspaper, 26-10-1997.

– E. Ghika, Testimonies from the heroes of the ’40s, Time Out Magazine, 27-10/2-11-2002.

– History of the Greek Nation, Vol. 15

– D. Sapranidis, History of Greek cartooning, 3,000 years of doubt, Athens 2001.

* Spyridon X. Mouratidis is a doctor of History of the Ionian University, painter and cartoonist.