Bestselling Cypriot Australian writer and performer Koraly Dimitriadis’ vivacious voice returns to rouse audiences with a debut collection of short stories in her book – ‘The Mother Must Die.’

Identity, divorce, sexuality, materialism, parenting, domestic violence, illness, grief, and the struggles of the working-class migrant are all themes on the authors’ literary stand with each their own witness to attest to unique experiences.

Readers are immediately invited to “step into the wog bubble for some real pain” in locations around Melbourne, and discover why broken people feel “it’s better to keep your real self-buried so nobody feels too uncomfortable.”

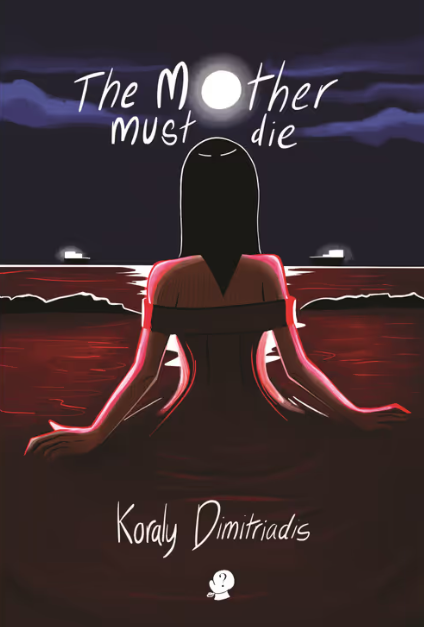

A greater portion of the book’s exterior is dipped in an ageing blood-stained crimson wash – where a woman, soon to be revealed as a “Mother” who can be seen merging into a sea of red, like blood – illustrating how Mother’s naturally embody the ocean, the earth, and life itself, yet can feel consumed by the world’s perceived expectations. This imagery also casts the notion that an escape from this overwhelming existence where “we’re all doomed” is possible, yet as Dimitriadis writes, the “Mother Must Die” in order to find it.

Transformative in her multi point-of-view approach, she interweaves varying personas ranging from the sex-conquest driven male club owner claiming that “men rule the world, end of story,” to the women who feel obliged to compete in the “race to the altar” but end up ditching the “scripted play” once they realise “you don’t have to subscribe to it.”

Dating apps, sexual liberation and self-pleasure are also highlighted as a deviation from the “wog mentality” that can only be cleansed with forced confessions, “conservatism, proper Greek behaviour, religion and ethics,” which metaphorically “grew on the fruit trees.”

By reimagining traditional culture through the trumpeting of taboo topics, Dimitriadis arms women while aiming to disarm the world, making it clear that her goal is to ostracise oppression itself and valiantly fight against the objectification of women.

Dimitriadis encourages women to go “where the music is the loudest” over the “dulling hum of the rangehood” in a Mediterranean kitchen, even if they are “the only wog chick” surrounded by Aussies. By venturing into the unknown, you “might just find yourself.”

As empowering writers often do, she uses the characters in the stories as a mirror to reflect some her own observations and her journey so far as a woman – “is it the writer writing the story or the story writing the writer?”

For those who never feel quite at home in “cold Australia” and see their bed as a “coffin,” Vicky and Haroula can sympathise. For casual couples who get stuck in a limbo of “elated to lonely,” Penny and Chris can relate. For the migrant Mothers and Fathers who are either estranged from family and “craving familiarity,” or surrounded by children during times of ill health who have “carried the burden of communication,” Francesco and Matriarch, Voula can understand.

Interspersing Greek and Cypriot phrases among the English further allows Dimitriadis to capture the depth and haunting reflections of some, “Pou ‘ne ta hronia?” “Where are the years?” and creates an expansive premise for enhancing the multi-cultural nature of the book.

Recipes and dreams feature in stories within stories, where descriptions noted on the back of photographs help to resuscitate a mother’s longing to connect with her daughter as she faces a seemingly inevitable medicated catharsis for post-natal depression.

Dimitriadis’ clever inclusion of a child who’s torn between two households and wishes to be a “mermaid” that “heals” from her favourite show, can be an innocent and momentary tonic to the “can’t have it all” feeling drawn out by what TV permits as the acceptable “representation of a woman.”

No matter the angle you’re viewing the world from, the road is difficult for mothers, for women. Survival comes down to finding peace within themselves amid all the noise, and if they can’t, physically, to use their soul to do it.

For Dimitriadis, who considers Cyprus her soul’s birthplace where “Aphrodite’s medicine lingers in the air,” she recommends that all we need to do is “breathe it in, absorb it… it heals.” That there is hope for the broken yet. That “you’re not broken, despite what society might think.”