By Alexander Billinis*

As we know, time travel is still not a possibility, and to recreate the past, even as a historian depending on documents, is still in part an act of fiction. The historian/writer/novelist is aided, however, in those cases where the physical scene remains more or less the same as the historical period you seek to discuss.

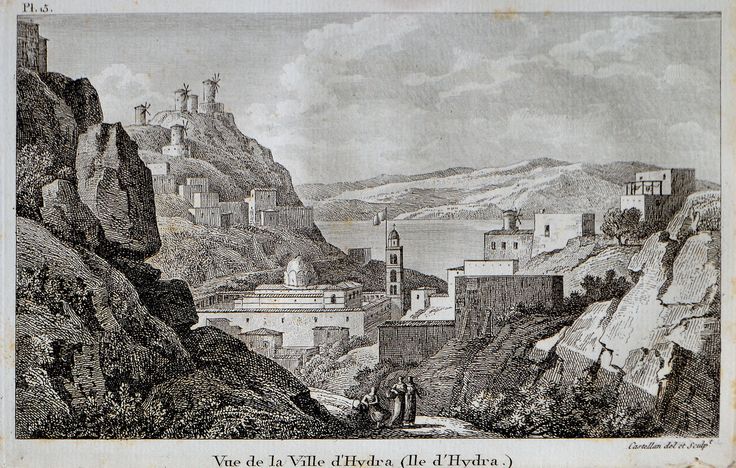

So it is with the island of Hydra, whose amphitheater-harbor remains largely in the same style and architecture as in the time of its glory days, right around the period of the Greek Revolution in 1821.

If we block out the digital accoutrements in our hand and the often-latest fashions of denizens and tourists, together with the catamarans from Piraeus and the yachts of shipowner and oligarch, we go back in time, a visit there can feel like time travel—there are no cars to tyrannize you, nor the concrete chaos of modern Greece.

So . . . let’s set the dial back two hundred and two years, to 1820.

Let us also remove the motors from the caiques which rely on sail and oar power, but the donkeys and mules still ply the lanes. In 1820, you can see less of the lovely ladies of the island, because they venture out less, and are generally in long, often ornate dresses and partially veiled—the Turks have controlled the Balkans for almost 400 years by this time, and their sartorial styles figure to a degree in local dress. Rather than the various foustanellas worn on the mainland, islander men wear baggy pants called vrakes. There will be fewer men in evidence, as nearly every able-bodied man from six to sixty is at sea.

This will not be immediately obvious if you do not speak Greek, but if you do, you will find that many people in the streets are not speaking Greek—though plenty of words will be understandable. They are speaking Arvanitika, a southern dialect of Tosk Albanian, an unwritten language which varies greatly from place to place and is full of Greek, Turkish, Italian, and various Slavic words. On the island, everyone speaks it, and many people, particularly the women, who travel less, might not speak Greek at all. The priests and administrators certainly speak Greek, along with other languages, and the majority of Hydriot men, who are sailors, captains, and shipowners, likely speak Greek along with a smattering of other languages, including Turkish, the Venetian dialect of Italian, and perhaps Russian or French.

Hydriots are a prickly breed, entrepreneurial and tough, yet also hospitable. If you sat down with one of them in the shade of a plane tree or inside on a low divan, perhaps smoking a long Turkish pipe, and managed to ask them who they are, they would speak of their patrida (though probably using another word) as Hydra, and their identity as Romioi . . . .

This needs a bit of clarification. The Turks divided their subjects into communities, known in Turkish as Milleti. All Orthodox Christians, from Belgrade to Beirut, were part of the Rum Milleti, which might be translated as the Roman/Byzantine community. The Ottomans conquered a very sophisticated civilization, the Byzantine, which had lasted for over 1000 years and had basically fostered successor states in Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania, all of which fell under the Ottoman sword. The Ottomans basically preserved some of the administrative and cultural apparatus of the Byzantium for their Orthodox flock, and the Patriarch of Constantinople, now appointed by the Sultan rather than the Byzantine Emperor, was both the spiritual ruler of the Orthodox faithful and their liaison to the Ottoman Sultan.

A specifically Greek nationalism might be familiar to those Hydriots who had traveled to major Ottoman cities or to the “Greek” communities abroad, but it was more the concept of Romiosini (Byzantineness) defined the Hydriots’ (and most Greeks’) identity at the time.

The world the Hydriots inhabited was a tough one, in 1820 there had only been peace in Europe for about five years, after Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo in 1815. While the Ottoman Empire managed—wisely—to avoid much of Napoleon’s wrath in Europe, her Orthodox subjects were not unaffected. For one thing, many Greeks lived either in the Ionian Islands, which in the space of a decade changed hands from Venice, to Revolutionary France, to a Russo-Turkish occupation, to Great Britain, and thousands of Greeks lived in the Austrian and Russian Empires, which had fought Napoleon.

Many Orthodox in the Balkans viewed the French Revolution as a model for their enslaved lands. One such individual was Rhigas Pheraios, an immigrant to the Austrian Empire. Typical of the hardy Greek immigrant then (and now), he had worked as a merchant, as an editor of the first Greek newspaper—anywhere—in Vienna, and as a conspiring revolutionary arrested by the Austrians in their key port of Trieste. The Austrians sent the revolutionary to the Turks’ frontier town, Belgrade (now Serbia’s capital), where they strangled him and threw his body in the Danube River. His ideas did not die with him.

Hydriots had done well by the Napoleonic Wars in particular, running the British blockade of French controlled parts of Europe, trading grain for gold, lots of it, in fact. There is a story, perhaps apocryphal, of one dashing Hydriot captain who had been caught by Admiral Nelson of the British fleet. This hero of Trafalgar asked the Hydriot, “What would you do if you were in my shoes?” The Hydriot replied, “I would hang you.” Taking the measure of the man, the Admiral is said to have remarked, “If I ever see you again, that is precisely what I will do.” The captain was Andreas Vokos, later to adopt the surname Miaoulis. Other Hydriots captured by the British were sent as convicts to Australia, the continent’s first Greeks.

While the gains from the decades-long Napoleonic Wars had been the icing on the Hydriots’ financial cake, island’s success was built on a strong maritime commercial foundation. The Hydriot sailors had honed both piloting and commercial skills in the difficult waters and politics of the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Seas. They were ubiquitous in the key Ottoman ports, such as Thessaloniki, Constantinople, Smyrna, and Trebizond, and also traded with major commercial entrepots such as Odessa and Trieste, both of which had very large and powerful Greek commercial communities.

Since 1774, Hydriots, like all Orthodox shippers in the Ottoman Empire, gained the right to fly the Russian flag on their ships, providing them with the protection of an Orthodox Great Power and a degree of extraterritoriality, yet the Ottoman yoke was worn rather lightly on Hydriot shoulders. Recognizing shipping as a knowledge business, the Hydriots founded the world’s first merchant marine academy, which still turns out graduates to this day.

The Turks did not settle on the island, which was basically self-governing. In exchange for a periodic levy of stalwart Hydriot sailors for the Turkish navy, the island was left to its own devices, with neither the Turks nor the islanders eager to upset the apple cart. Service in the Turkish navy brought vital experience and tactical knowledge to the island, as did the periodic battles with the same Barbary Pirates that induced the young United States to go on to its first foreign war, against the Emirs of North Africa (where Greeks also fought on the American side). As such, most Hydriot ships were armed with cannon, and possessed of sailors knowledgeable in their use.

Just two hundred years earlier, in the 1600s, Hydra had none of this, the spectacular success of the island is as fascinating as her heroic role in the War of Independence, as the island was largely a barren rock rising often vertically out of the Saronic Gulf, with a few decent anchorages and no more than a few hectares of arable land. The Hydriots had been refugees fleeing chaos on the mainland or other islands and they turned to the sea because that was the only agency available to them. With no maritime tradition, they learned from other Greeks or from the still ubiquitous Venetians, and in the space of a couple of generations their island had become the biggest shipping center of the Eastern Mediterranean, supporting in 1820 a population about ten times larger than today.

Like Greeks before and after, they took to the sea to find agency in a life where it did not exist, and they found it in financial terms. Many Hydriots, particularly the wealthiest, were satisfied with this state of affairs, yet other Hydriots wanted political and cultural agency as well economic. Rhigas Pheraios had been dead for twenty years, but an increasingly literate society read—and remembered—his words.

In Odessa, in 1814, a trio of Greeks formed a secret society dedicated to the liberation of Greece. There numbers soon included Hydriots, particularly men of the middle class, the section of society that everywhere leads and inspires national liberation movements.

In 1820, the business of Hydriots was business, yet there were many Hydriots waiting for a sign.

It was not long in coming. When it came, though they pondered the costs, they answered.

The rest, is history, and honor is due.

READ MORE: Spectral Smyrna in Izmir

*Alexander Billinis is an instructor at Clemson University, in South Carolina, USA. He is a licensed attorney, with a former career in law, real estate management, and international banking. He has lived and worked in Greece, the UK, and Serbia, as well as shorter work or study assignments in Bulgaria, Hungary, Germany, and Chile. A citizen of both the United States and Greece, he is married and the father of two teenage children.