By Ilias Karagiannis

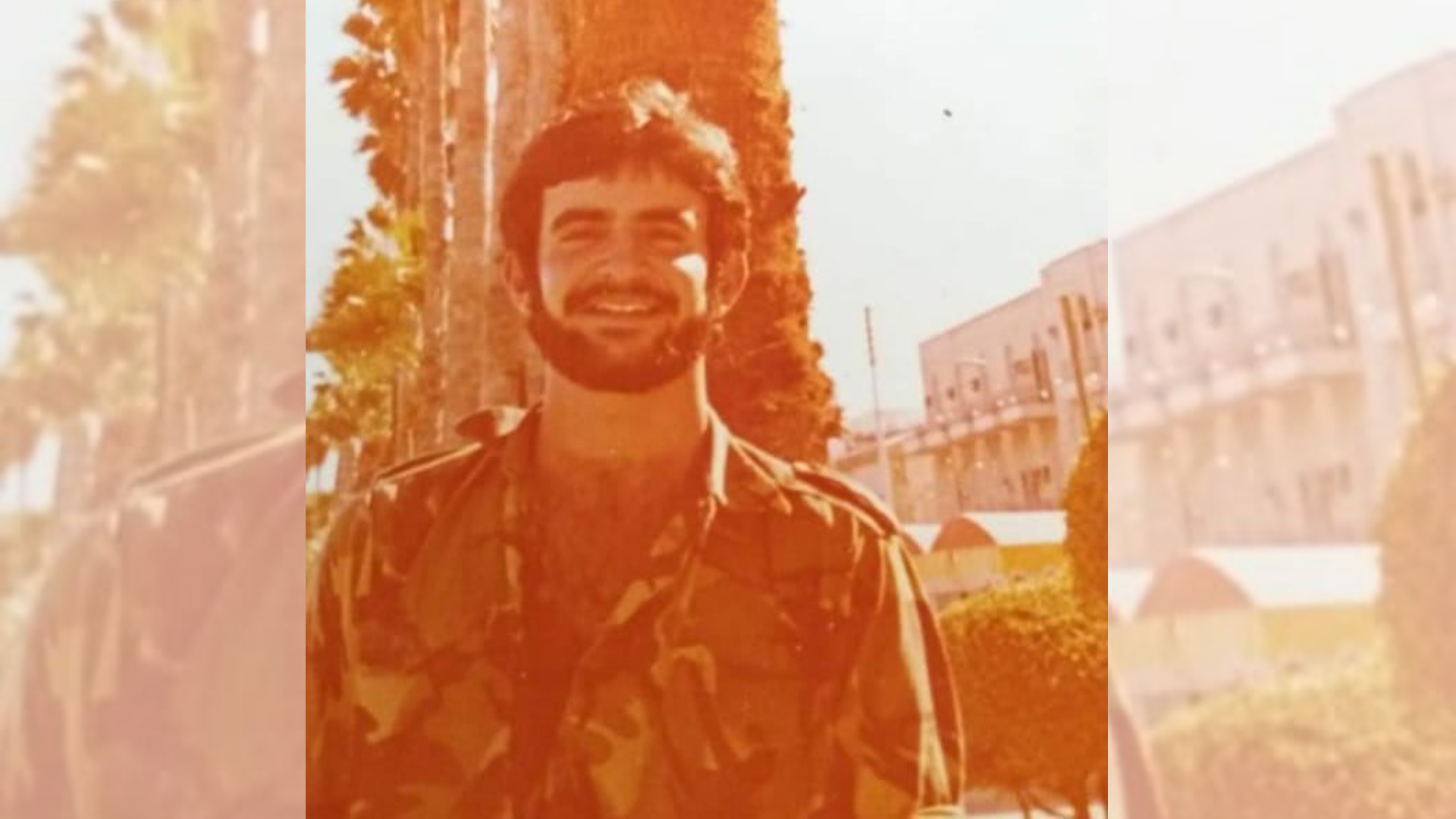

A few days before 20 July 1974, Fanos Christoforou had completed one year as a soldier. At that time, mandatory military service in Cyprus was two years, and just days before the Turkish invasion of the island, the relevant minister announced its reduction to one year. It was joyous news for all the young men.

But fate had other plans. Those were the carefree days of summer relaxation in a Famagusta that then shone brightly as a coveted tourist resort.

Everything seemed in its proper order until the dawn of 20 July 1974. At 19, full of dreams and zest for life, Fanos suddenly faced a nightmare.

“Everything happened suddenly. No one knew anything,” he tells The Greek Herald in an interview marking the dark 50th anniversary of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus.

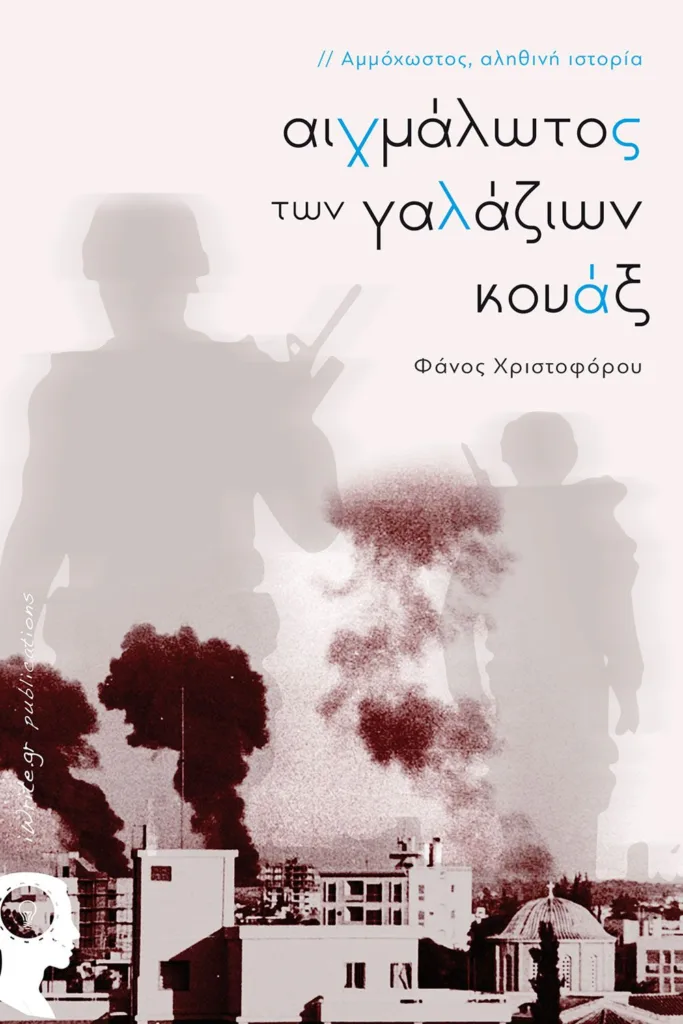

In his book ‘Prisoner of the Blue Kouax’(published by iWrite publications), Fanos details the first hours of the Turkish invasion with breathtaking precision: “Your gaze is vacant, awkward, whether you look at the others beside you in the car or not. Sitting with the rifle between your legs, holding it with both hands, your whole body trembling from the jolts. You feel that others are having the same thoughts and feelings as you. War. The car continues its journey to the front line, where we will meet death.”

He reconstructs the painful memories of the invasion in a concise, experiential book, imbued with his unique humour, as well as fear, anxiety, joy, and sorrow.

“I never intended to write a book about what we experienced during the invasion. On the contrary, with great effort, I managed for decades to forget everything that happened so I could move forward in life unimpeded,” Fanos says.

“But it seems that as the end approaches, the impact of what happened no longer matters, and like a volcano, my memory erupted due to the compression it had endured for so many decades.”

But how did he decide to convey his experiences into the pages of a book?

“On 20 July 2016, I had a vivid dream that I was in the Land Rover heading to the front line. I had the same feelings as back then. I woke up abruptly, thought about it, took pen and paper, and wrote mixed notes about everything I remembered, not stopping until the end of August,” he answers.

In a month, Fanos wrote his book.

“It was as if the events were waiting compressed to decompress, to explode, and come to the surface,” he says.

Disappointment and volatile psychology

The invasion indelibly marked the soul of Fanos.

“Whenever I sit down to rest, only the things I experienced until I was 20 come to mind automatically. Everything I did and experienced after I was 20, I have to make an effort to remember. What I lived through in the city, I relive every day, as if no time has passed. Every effort to expel them from my mind is in vain,” he says.

The Turkish invasion of 1974 tore apart Cyprus’ peace, spreading death and terror. Young and inexperienced, he witnessed the horrors of war, saw friends, compatriots, and enemies fall dead, heard deafening explosions, and saw houses and monuments destroyed. His homeland was split in two.

For a 19-year-old with his whole life ahead of him, war is a deviation from normalcy. Fanos found himself on the front line, where the ground shook from the bombings. He vividly recalls an attack and describes it.

“I remember chaos breaking out. The ground was shaking, smoke everywhere, each bullet from the machine gun seemed to be coming straight at me. I was very scared. Terrified because I was exposed. Like a fly in milk. I thought the Turkish pilots were targeting only me. I started crying, completely alone and helpless amidst the chaos. My 19-year-old life condensed into seconds. It felt like an eternity. I cried and, in my despair, said: ‘Holy Mother, help me, and I will come to Tinos to worship you’,” he explains.

On the front line, Fanos’ thoughts were many and came quickly, like bullets from a machine gun.

“I thought everything was a game. A cinema movie. That it wasn’t real. That the dead were a lie. With the first shell, I tried to delude myself, to try to gather whatever logic and mind I had and expel from within me any emotion that didn’t match my logic. Reality has nothing to do with what movies show. The bullet hits the person next to you; you pull away from them, wondering if the next bullet will hit you, and you say to yourself: ‘I’m lucky, thank you, God, I got away with it’,” he says.

Soon, though, even the bombings became routine, as he confesses.

“The bombings from the planes had become monotonous. Of course, I trembled with fear. You heard the hum and looked for somewhere to hide. A trench, a tree trunk. To feel safe, that the Turk couldn’t see you. And you wait. Whether you’ll be killed or remain alive,” Fanos says.

The psychology in war is indeed volatile, as confirmed by the recounting of a harrowing incident.

“One day, the planes came. That day, they had a different colour, and the first plane dove and dropped the bomb in the port, trying to hit the tower with our post. Such joy I had never felt. The same for all of us there. We believed the bomb fell in the old town, among the Turks. We thought the planes were Greek, and our joy was indescribable. We cried, shouted… Until bullets from the second plane rained down around us. The third plane dove again on our own. We had been lied to again. Our joy lasted seconds but was unforgettable. A great disappointment. We felt so alone,” Fanos details.

The old Kouax and the Cyprus issue today

Another disappointment came from his battalion commander, whom Fanos considered his favourite. He sent him and the radio operator on a suicide mission. To guard a school.

“We had not realised that he left us there to mislead the Turks, to delay the tanks coming to capture the city, so our battalion could retreat and save our soldiers,” Fanos explains.

When he realised this, Fanos started running aimlessly. He went to Saint Luke’s, to his aunt’s house, and there he learned about the Turkish invasion of Cyprus from men from the Electricity Authority who came to rescue his relatives.

“The Turks are coming. They landed in Kyrenia from Turkey. Today the line at Mia Milia broke, and they’re coming this way,” they told the terrified Fanos, for whom there was no room in the car. Again, he was left alone. He ran to his battalion’s camp. Desolation.

“I didn’t know what to do, where to go, what to think. The hum of the tank engines was getting closer. I started crying. I had to do something. I was afraid of being captured. I thought about committing suicide. But it wasn’t easy,” he says.

He thought of the British base at Saint Nicholas. He went there but was asked to disarm. He started running again, aimlessly. Where reality meets magical realism. To the quacks.

I asked him what the quacks were, mentioned in his book’s title. Is it a motif that keeps him tied to his homeland? The Old Quack, a frog, begs him to stay in Cyprus to open the water taps. Not to leave. And shortly after… darkness. As if a blanket covered his memory. He remembers nothing. He found himself at the Higher Military Command of Larnaca in a frantic journey that ended weeks later in exile in Greece.

In Greece, he became a distinguished lawyer, trying to repress his memories and succeeded until that morning of 20 July 2016, when he decided to write his book. Hope was blazing inside him.

“I think that those born ten years after the invasion would hear everything like fairy tales. We who lived through it consider them fairy tales. It seems incredible, a lie, that we experienced such things at such ages. I cannot distinguish the lie from the truth. Back then, everything we lived was a lie, and today we live in reality. Or what we lived back then was reality, while today we live in a lie?” Fanos says.

Fanos of 1974, scarred by war and exile, became Fanos of today, a man full of resilience, hope, and love for his homeland. For life…

His story, like the story of thousands of other Cypriots, stands as an immortal testimony to the human will to live and be free. As our meeting concludes, in the hospitable “Athens Cypria Hotel,” I ask him about the Cyprus issue and if he foresees a solution. He answers me briefly, trying to dispel the pessimism.

“Many believe we will never be free. I don’t agree. The Cypriots’ vitality and persistence to survive in their homeland are evident. We will never let our country be completely lost. From generation to generation, we keep the hope of our free homeland alive. We, Cypriots, with our insistence on survival, will achieve freedom for Cyprus,” Fanos concludes.