By George Lois – Colonel (Ret.) (Armoured)

On 26–27 April 1941, the Battle of the Corinth Canal took place, marking the penultimate military engagement of the British Expeditionary Force in Greece during World War II. It was a German airborne operation involving elite German paratroopers targeting the strategically vital maritime passage, which was bravely defended by the Commonwealth “Isthmus Detachment.”

From the onset of the German invasion, the Corinth Canal had been a focal point for the enemy, deemed crucial for their complete domination in Greece, as well as being an important conduit for fuel supply lines from the Black Sea to Axis forces operating in North Africa. To secure it, the airborne Operation Hannibal was planned, which aimed for the vertical encirclement of the retreating British Expeditionary Force, with the objective of capturing the transportation bridge over the Corinth Canal to disrupt the withdrawal of Allied formations from designated evacuation ports in the Peloponnese to Crete.

The daring undertaking was assigned to the battle-hardened 7th Parachute Division, commanded by Major General Wilhelm Süssmann, stationed near Plovdiv, Bulgaria.

Having intercepted some intelligence about German intentions, British command decided to swiftly organise a defensive setup in the Corinth Canal area on 24 April 1941, hastily forming the Commonwealth “Isthmus Detachment.” This eclectic force consisted mainly of disparate British, Australian, and New Zealand sub-units (ANZAC), of reduced composition, drawn from various Allied units as they passed through the Peloponnese.

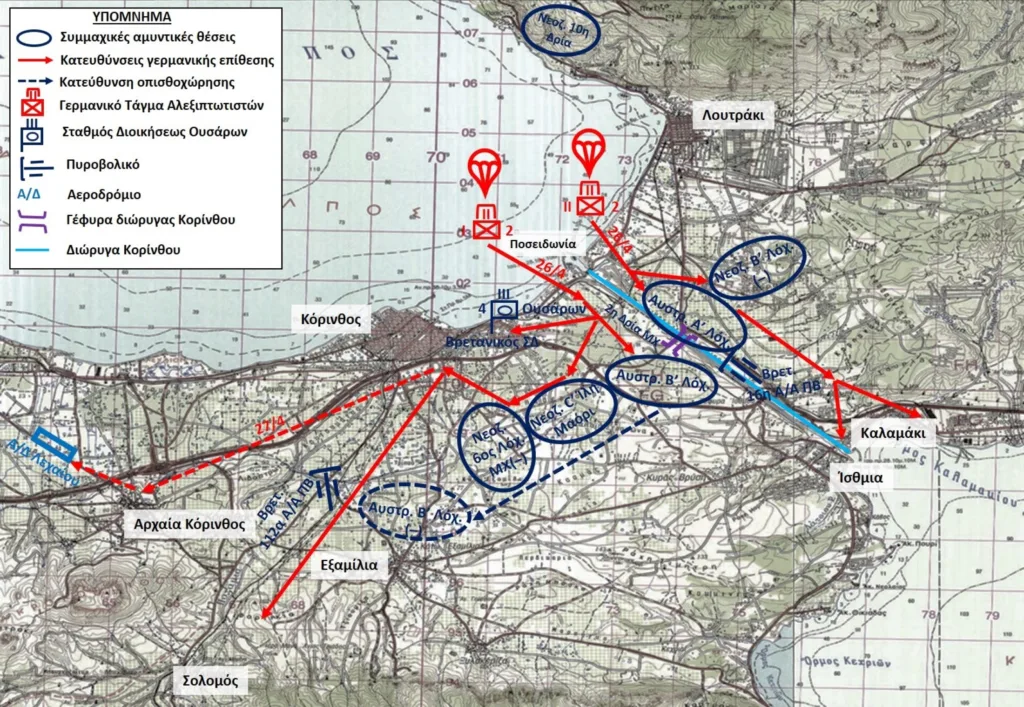

Specifically, on the night of 25 April, their deployment at the Isthmus was as follows:

– The Command Post of the British 4th Armoured Hussars was located east of Corinth, with a Rifle Section oriented towards the northwestern end of the canal. The commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Lillingston, was in charge of the “Isthmus Detachment.”

– The A and B Companies of the Australian 2/6 Infantry Battalion were stationed defensively on either side of the canal bridge.

– The British 16th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery and the 122nd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery were primarily positioned along the canal and on the Corinth–Argos route, along with a Greek anti-aircraft detachment.

– The C Troop of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and the Carrier Platoon of the New Zealand 28th Infantry Battalion (Māori) were stationed southeast of Corinth.

– The New Zealand 6th Field Company was deployed south of Corinth, with a section of sappers near the western side of the canal, which had been undermined with explosives.

– The independent B Company of the New Zealand 19th Infantry Battalion was fortified on a hill approximately 800 m northeast of the bridge, with a platoon in reserve 5 km north of Loutraki.

The total estimated strength of the personnel in the above Commonwealth units was around 41 officers and 770 soldiers. However, the troops were extremely fatigued from three days of retreat, and their ammunition, heavy weapons, and available mechanised combat resources were very limited. The Australian and New Zealand officers were not professional soldiers but reservists who left their peaceful civilian lives to enlist and fight against a foreign enemy thousands of miles away from their homelands.

Moreover, the day of 25 April held particular significance for Commonwealth forces, as it was the anniversary of ANZAC Day, established to honour the Australian and New Zealand soldiers who fought at Gallipoli against the Turks during World War I, precisely 26 years earlier. Surely, that night, the men of the Australian A and B Companies and the New Zealand B Company must have been emotionally charged as they prepared psychologically for an expected enemy airborne assault in the coming hours.

On that day, the German 7th Parachute Division was airlifted from Plovdiv to the captured military airfield at Larissa, which had been selected as a launch base for the upcoming Hannibal operation due to its proximity to the Corinth Isthmus area. The mission of the airborne assault on the canal was assigned to the well-trained 2nd Parachute Regiment under Colonel Alfred Sturm, to which were attached special engineering and combat support detachments. The unit organised two assault groups, each at the reinforced battalion level, and a command group that would be dropped on either bank of the canal.

The total strength of the German assault force was approximately 105 officers and 2,100 soldiers. It was noted that 270 Junkers 52 transport aircraft and about 60 DFS 230 gliders were required for the airborne transport of the German paratroopers and their equipment. The offensive operation would be supported by 20–30 Junkers 87 (Stukas) dive bombers, an unknown number of Junkers 88 fighter-bombers, and 80–100 Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighter aircraft.

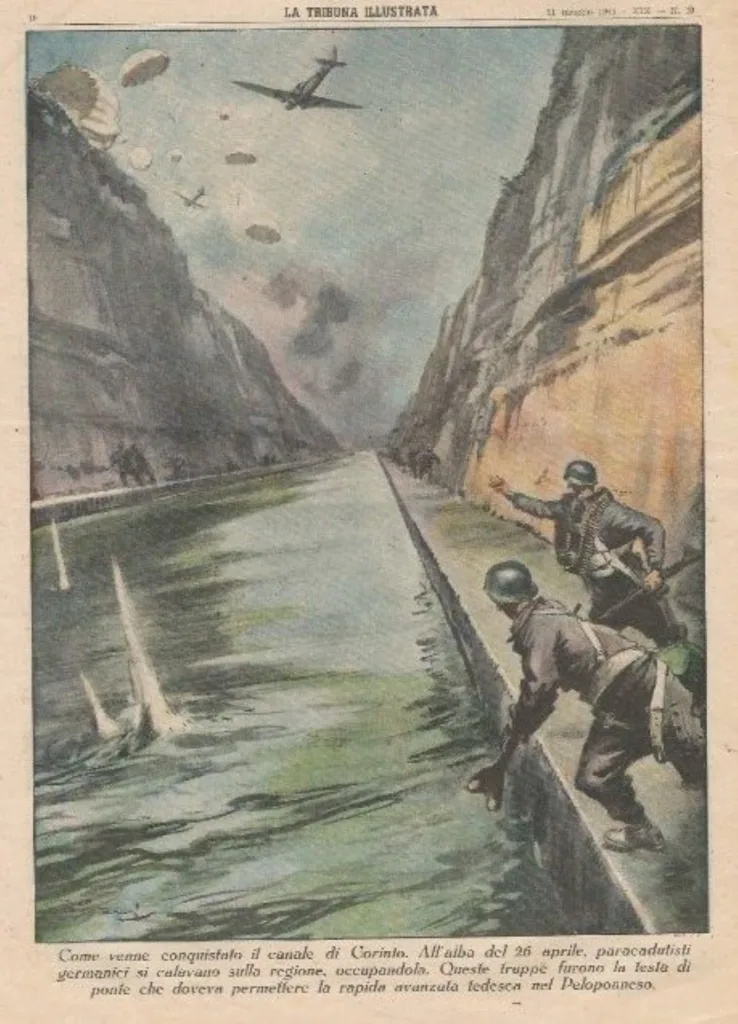

The German airborne Operation Hannibal commenced at 06:30 on Sunday, 26 April 1941, when the first Stuka bombers appeared over the Corinth Canal, completely surprising the men of the Commonwealth “Isthmus Detachment,” as they emerged suddenly from the unusual morning fog, flying silently just 30 m above the sea surface. From that moment, a relentless bombing campaign began, targeting artillery and defensive positions. The British gunners returned fire en masse, firing incessantly, but soon many of their guns were rendered inoperable.

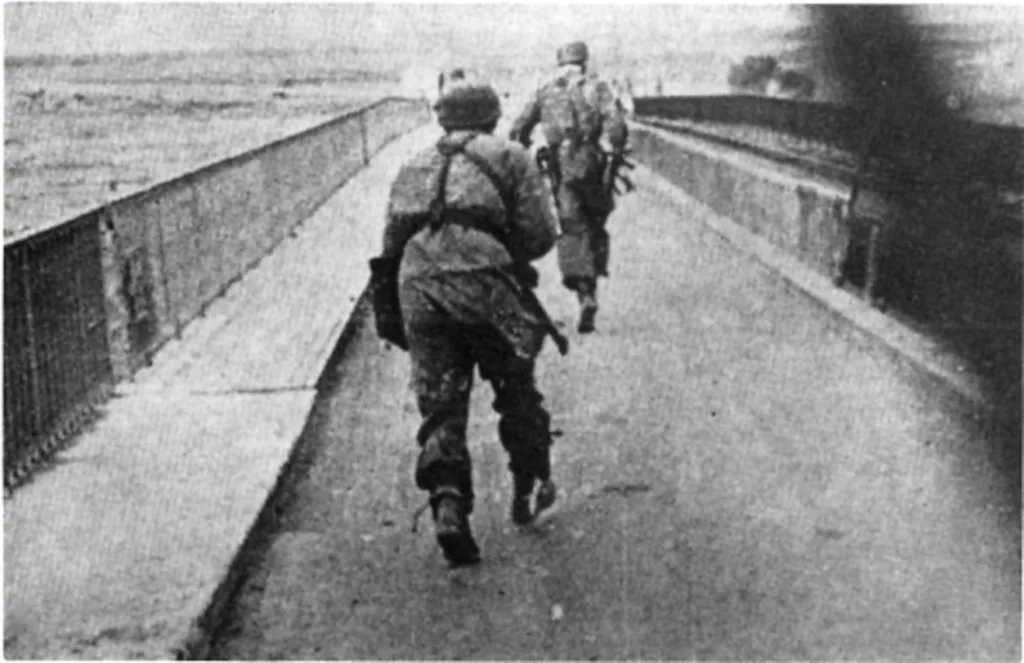

Around 07:10, six gliders landed near both ends of the bridge, disembarking a German Engineering Section aiming to seize it intact and remove the explosives from its metal framework. Shortly thereafter, around 07:25, the first wave of transport aircraft arrived, delivering the main German assault force to the designated drop zones. Slowing their speed and descending to a height of just 90–100 m, they opened their side doors and began the jumps of the German paratroopers. In the following minutes, the sky above the canal filled with strange coloured “umbrellas,” from which armed fighters and other items hung. The Commonwealth soldiers looked on in shock, having never witnessed such a bizarre sight before.

Suddenly, between 08:00 and 08:30, the bridge over the canal was blown up, and its debris cascaded into the canal, taking with it the German soldiers working on it. According to the official account, the terrible explosion was triggered by two officers of the New Zealand Engineers, who were hidden in a makeshift shelter. Among them, Captain J. P. Phillips aimed with a rifle from a distance of 150 m at the deactivated explosives stacked in the middle of the deck, managing to detonate them with his second shot, assisted by observer Lieutenant J. T. Tyson. In the post-war period, both were awarded the Military Cross for their actions.

To the east of the blown-up bridge, the soldiers of the Australian A Company were desperately fighting against the German paratroopers of the I Battalion, who were suddenly attacked by the New Zealand B Company. However, due to their numerical superiority, the enemy overwhelmed the stubborn resistance of the ANZACs between 11:00 and 11:30, capturing many prisoners, except for a detachment of New Zealanders who managed to withdraw towards Megara.

To the west of the canal, the landed companies of the II Parachute Battalion virtually annihilated the British 4th Armoured Hussars, pushing back the sections of the Australian B Company, which managed to partially regroup on a hill north of the village of Examilia, under continuous enemy pressure. During their rapid advance, the Germans swiftly attacked the weakened New Zealand C Troop and the Carrier Platoon of the Māori. Although they fought heroically, the ANZACs were forced to retreat. Along the way, they abandoned the Bren Carrier vehicles after pushing them into a deep ravine to disable them, while most escaped on foot towards Argolis, guided by local Corinthian villagers.

The 6th Field Company mounted a stout defence, locally repelling the German paratroopers. The New Zealand sappers would fight with unmatched bravery until 16:00, when, due to a severe shortage of ammunition, they dispersed into small groups towards the south; unfortunately, many were captured in their escape attempts. Around the same time, the remaining soldiers of the Australian B Company withdrew in the same direction, leaving their occupied positions in the Examilia area.

Earlier, at 13:00, Mayor Andreas Markellos had surrendered Corinth to Colonel Sturm without resistance, under the threat of a devastating bombing of the city by Stuka aircraft.

The tactical situation changed momentarily when the A and D Companies of the New Zealand 26th Infantry Battalion arrived from Tripoli as reinforcements for the “Isthmus Detachment.” However, their vehicle columns were halted around Solomos, coming under heavy air attack. They continued on foot and eliminated a forward German patrol while moving to the heights north of the village, where they clashed with a strong unit of German paratroopers. Eventually, just before sunset, the two New Zealand companies disengaged from Solomos and returned, realising they had no chance of reaching Corinth and faced the risk of being outflanked by the enemy.

In the eastern sector, the German paratroopers captured the village of Kalamaki after occasional skirmishes with small armed groups of retreating Greek soldiers and built a makeshift pontoon bridge at the southeastern entrance of the canal, using boats, suitable for infantry and light vehicles.

The next day, Saturday, 27 April 1941, the German invaders conducted a sweep of the wider area, overrunning an unidentified ANZAC unit that had remained in the archaeological site of Ancient Corinth after a bloody clash, and subsequently reached the military airfield at Lechaion.