By Ilias Karagiannis

The waves carried sorrows and hopes. On the horizon was the unknown. Suitcases loaded with dreams and nostalgia, while the Greek diaspora landed on the shores of Australia in the 1950s and 60s, seeking eutopia, a refuge from the relentless difficulties of post-civil war Greece.

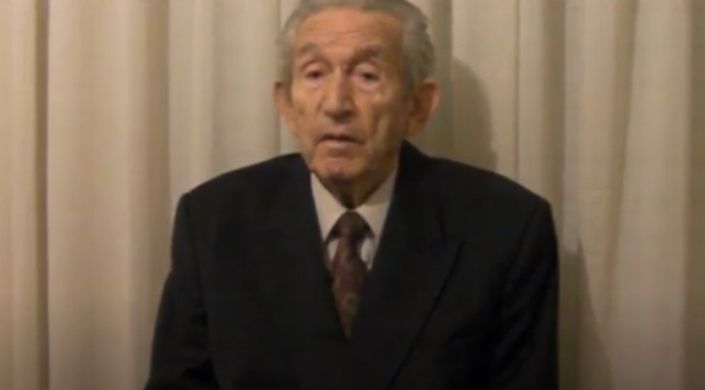

“The circumstances of life compelled me to leave. There was no electricity, no water, no cars. I left my elderly parents behind,” Greek Australian Dimitris Pavlakis says.

“I didn’t know what life would be like in Australia. I wore one of my father’s jackets. I was hoping I would find something to eat on the boat and reach Australia to become a human being,” Michalis Protopsaltis adds.

The stories of the Greeks who left Kythera for Australia are recorded by a program that is the guardian of the community’s memories.

The educational program “Kythera: Stories that build bridges” completed its first phase, implemented by the 6th Regional Centre for Educational Planning, Attica in collaboration with students and teachers of Primary and Secondary Education of Piraeus, as well as with the support of the Kytherian Association of Athens and the Nicholas Anthony Aroney Fund in Australia.

The scientific guidance of the program was provided by The Oral History Association and the Postgraduate Program “Public History” of the Hellenic Open University. Participants attempt a biographical approach to the migration history of Kythera.

The Greek Herald, also a longstanding guardian of the Greek and Cypriot community in Australia, recently conducted an interview with Archontia Mantzaridou and Kyriaki Melliou, two vital members of the program’s scientific committee. With a history spanning 97 years, The Greek Herald has become a pillar of society, and sought to delve deeper into the inspiration behind their work.

During The Greek Herald’s interview with Ms Mantzaridou and Ms Melliou, we inquired about the motivation behind the development of the educational program “Kythera: Stories that build bridges.” We also explored their objectives in fostering connections among the diverse generations involved in the program.

“About six years ago, as coordinators of an educational project at the 6th Regional Centre of Educational Planning in Attica, we took the scientific and pedagogical responsibility of the schools in Kythera and the first thing we did was seek information about the island and its history,” they said.

“We quickly found with interest that the main element that characterised the island, for long periods of time in its modern history, was immigration. At the same time, wanting to organise an educational program of local history we knew that in order to be innovative and attract the interest of teachers and students, we needed to converse with the modern trends of history. For this reason, we turned to oral history. Oral history, as Paul Thompson relates, is a story structured around people, it animates history itself and broadens its horizon, it brings history into the community and takes it out of it.

“The students, as part of the program, were invited to rediscover the history of their country through narrations of the lived experience of its unsung protagonists.

“Starting from specific methods and techniques suggested by oral history, the aim is to establish an archive of oral testimonies of those Kytherians who migrated to Australia and either returned again to their island or are still there in their new homeland. These oral testimonies will be material for successive readings by the students. The witnesses themselves become sources of history. Students connect with previous generations, rediscover them, and through comparisons, critical readings and transformations come into their own today to interpret the social phenomenon of migration.

“They re-connect with the history of their land, which is no longer a text in a book, it is not something distant and impersonal but it is the voices of people who share their personal memories and their words, give the human dimension, make the unseen visible and children learn that every person is part of history.”

The story of the ‘unsung heroes’

The historical period involving the migration of Greeks to Australia remains relatively underexplored. This program may potentially contribute to a more in-depth analysis of this aspect of history.

“This program does not seek simply to become a miniature of the general history our students are taught. It has a special value because it will allow our students to see things and situations, logics and mentalities and even conflicts that are not visible when we move in general history,” the women said in their interview.

“We know from general history that there was a huge stream of immigration to Australia in the 1960s.But we know much less about how a Tsirigotis of 20-30 years old, who until then had been farming fields, had some animals, maybe fishing, and how this man made the big decision for a trip to the other side of the world.

“What were his feelings, what were his fears, his hopes. What difficulties did he have until he arrived, how the groups were organised and supporting each other led him to make the big decision. How they experienced this journey of 30-40 days until they reached a distant continent unknown among strangers. How the first of them took the streets and created the first slots for the next immigrants to come from home. How the networks were then established and maintained between the island and the distant continent. What institutions they built there in order to endure at first and prosper afterwards.

“What role did the church play? They took in their suitcase food, some objects, the photograph of their loved ones. Therefore, as mentioned above, oral history comes to humanise academic history, to make the personal experience, through the memory of the martyrs, a part of history.”

As Alessantro Portelli said, “oral sources tell us not only what people did but also what they wanted to do, what they believed they did, what they think today about what they did in the past.”

In the educational program, students will conduct the interviews and will even draw inspiration from them to create a poem.

“The students found it extremely charming that they will film, record the narratives and then many choose to create digital representations or transform them. For example, the students of the high school created, based on the interviews of Dimitris Pavlakis and Manolis Cassimatis, a poetic event which they called “The Immigrant” captured in the form of a digital narrative,” they said.

“I think what most adds value to students is the fact that they understand that the people they see around them every day have experienced the significant changes that they study in the classroom, that it’s part of their history. With these everyday acquaintances they converse and get to know them again.

“Philippos Sklavos, Evanthia Douvri Protopsaltis, for example, are not the neighbours with whom they say “good morning” and the parents with which they exchange friendly visits, but become protagonists of the history of their country. This changes the sense of importance. They understand that they don’t have to be the next Martin Luther King or Marco Polo to be seen as having achieved something important. The story of the unsung hero is also history.”

The trembling voices, trauma and redemption

During the interviews we thought there would be some touching moments, which we asked Mantzaridou and Melliou to share with the readers of The Greek Herald.

“The most touching part of the program is that some of the witnesses have passed away. But their voices are now part of the story of their beloved island for generations to come. During the interviews, all the witnesses were moved,” the women explain.

“Indicatively, I remember during the interview with Vassiliki Hlentzou when she was talking about her beloved uncle who sent her the invitation to go to Australia and then called the lad who would become her husband, she said in a trembling voice “he was a holy man.” It is through these moments that you understand the difficulties, trauma or redemption of everyone. These references to the valuable invitations made by relatives or friends in Australia to those who wanted to try their luck in the new homeland, show the extent to which their waiting was imprinted deeply in the memory of the immigrants.

“Also, some phrases used by the witnesses are shocking, such as when Michalis Protopsaltis talks about the preparations he made before he left for Australia, wearing his father’s jacket that reached to his knees. He said everything was like a dream.”

How important is collective memory for the phenomenon of migration?

“Collective memory corresponds to the transmission of the past from generation to generation. The collective memory of migration is important for the whole of Greece. It is very important for Kythera. However, even such powerful experiences if left to oblivion, if not imprinted, risk being lost in the dust of time. So it’s important now to have a conversation with these people so that the new generation can get in touch with this experience,” they said.

“The memories of the people who faced the experience of migration become the link between the past and the present. We know that our program will at the same time shape the collective memory of the island and especially the collective memory around the migration of its inhabitants. That power is also a huge responsibility.”

The members of the program also created a touching 22-minute video, which encapsulates their effort.

“The program began in November 2019, when a three-day seminar was organised for the coordinators of the educational project in cooperation with the Oral History Association in Piraeus, where we were based. The program was then launched in Kythera and in collaboration with the Kytherian Association of Athens and the Nicholas Anthony Aroney Fund in Australia, the schools of Kythera were given the appropriate equipment for the interviews. But then the pandemic began and the program could not proceed as planned,” the women said.

“However, inspired teachers had believed in the value of the program both for Kythera and especially for their students, and they interviewed Kytherians who had experienced immigration in Australia and had now returned and lived in their home country.

“These interviews were presented in November 2023 at a closing event of the first phase of the program. In the period that followed, the body of Education Consultants was reconstituted and in the new educational scheme the program “Kythera: Stories that build bridges” continues its course from the Directorates of Primary and Secondary Education of Piraeus.

“The director of Primary Education of Piraeus, Athanasia Meidasis, and the director of Secondary Education of Piraeus, Dionysios Anastasopoulos, marked the continuation of the program. In the new phase the focus is now also on the Greek schools of Australia with the aim of their own participation.”