Scientists have been working for more than a century to decipher the Antikythera Mechanism, which is a hand-powered, 2,000-year-old device used by ancient Greek’s to calculate astronomical positions.

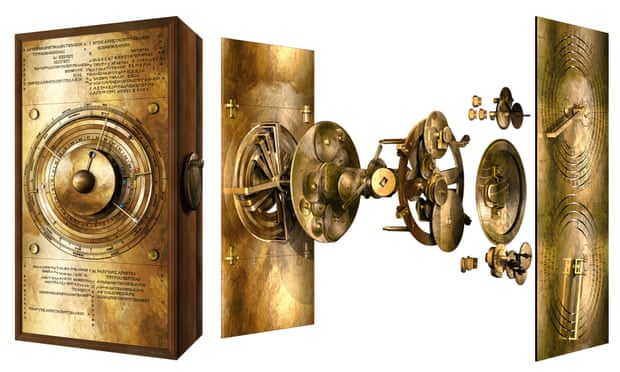

Now researchers at University College London (UCL) believe they have solved the mystery of the ‘world’s oldest computer’ by building a digital replica with a working gear system at the front – the piece that has eluded the scientific community since 1901.

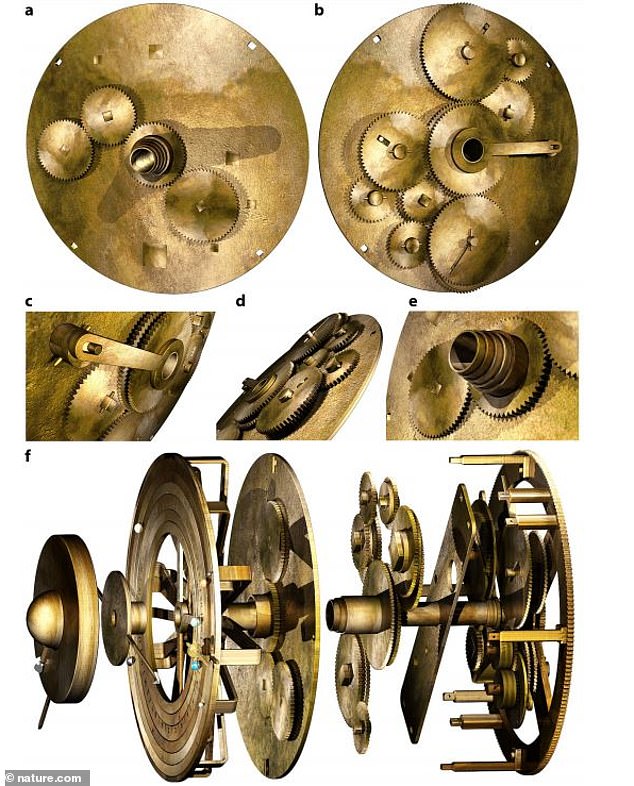

Using a combination of X-ray images and ancient Greek mathematical analysis, the team decoded the design of the front gear to match physical evidence and inscriptions etched in the bronze.

The digital result shows a center dome representing Earth that is surrounded by the moon phase, the sun, Zodiac constellations and rings for Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

“Ours is the first model that conforms to all the physical evidence and matches the descriptions in the scientific inscriptions engraved on the Mechanism itself,” lead researcher, Professor Tony Freeth, says in the journal Scientific Reports.

“The Sun, Moon and planets are displayed in an impressive tour de force of ancient Greek brilliance.”

Thinking behind the new research:

In 1901, divers looking for sponges off the coast of Antikythera, a Greek island in the Aegean Sea, stumbled upon a Roman-era shipwreck that held the highly sophisticated astronomical calculator.

The Antikythera Mechanism has since captivated the scientific community and the world with wonder, but has also sparked an investigation into how an ancient civilisation fashioned such an incredible device.

Michael Wright, a former curator of mechanical engineering at the Science Museum in London, pieced together much of how the mechanism operated and built a working replica, but researchers have never had a complete understanding of how the device functioned. Their efforts have not been helped by the remnants surviving in 82 separate fragments.

Writing in the journal Scientific Reports, the UCL team describe how they drew on the work of Wright to work out new gear arrangements that would move the planets and other bodies in the correct way. The solution allows nearly all of the mechanism’s gearwheels to fit within a space only 25mm deep.

The researchers believe the work brings them closer to a true understanding of how the Antikythera device displayed the heavens, but it is not clear whether the design is correct or could have been built with ancient manufacturing techniques.

The concentric rings that make up the display would need to rotate on a set of nested, hollow axles, but without a lathe to shape the metal, it is unclear how the ancient Greeks would have manufactured such components.

“The concentric tubes at the core of the planetarium are where my faith in Greek tech falters, and where the model might also falter,” Adam Wojcik, a materials scientist at UCL, told The Guardian.