The story behind ‘Into the Moonlit Village’ is as captivating as the work itself.

Poet Poli Tataraki, born in Crete but raised in Australia, first encountered Michael Winters’ artwork at an exhibition 14 years ago. Drawn by his depictions of Greece, she travelled from Dubbo to attend the event. It was a “serendipitous moment,” says Poli, that sparked a connection that would later blossom into a powerful collaboration – a bilingual exploration into the Battle of Crete, connecting World War II with Minoan history through poetry and art.

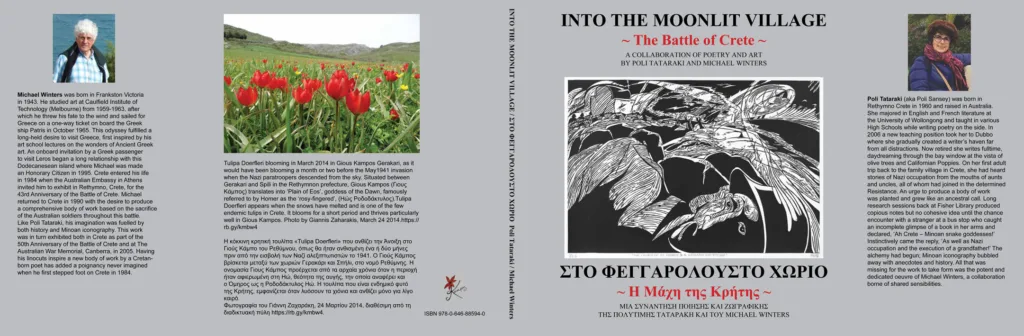

The artworks: Harrowing scenes of war

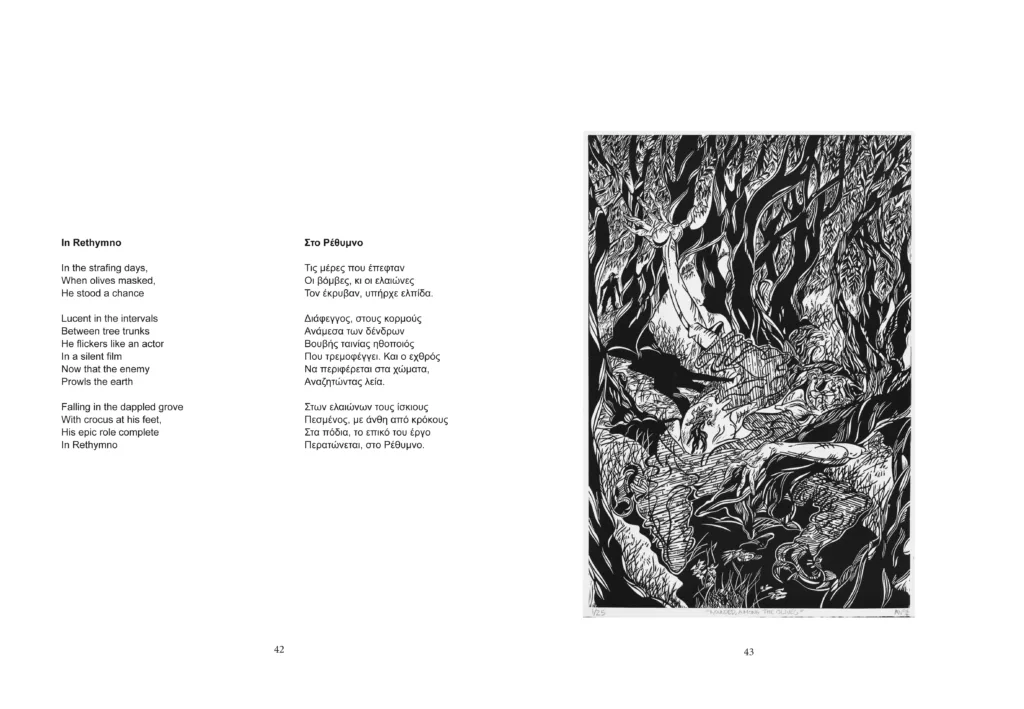

The linocuts were produced in 2004 after several periods in Greece. In 1984, Michael attended the 43rd anniversary of the Battle of Crete on the island but returned to create more works based on stories he heard. An 18-month stint at Argiroupoli, a mountain village just outside Rethymno, allowed him to focus on works as part of the Australian Government’s large Battle of Crete exhibition in May 1991.

“I needed to be there to produce these works and was fascinated by Minoan Culture on the one hand and El Greco, an artist whose works I admire, on the other,” Michael says, remembering his time on the island when his children were aged two and eight.

“I saw the destructiveness of Nazis on people’s homes, icons on walls and family heirlooms. I saw the pointless destruction and remnants of houses. The thought of young Aussies, 18 and 19, fighting for their lives in that landscape, all the way from Australia, with only a small knowledge of Cretan history, just added to the pathos.”

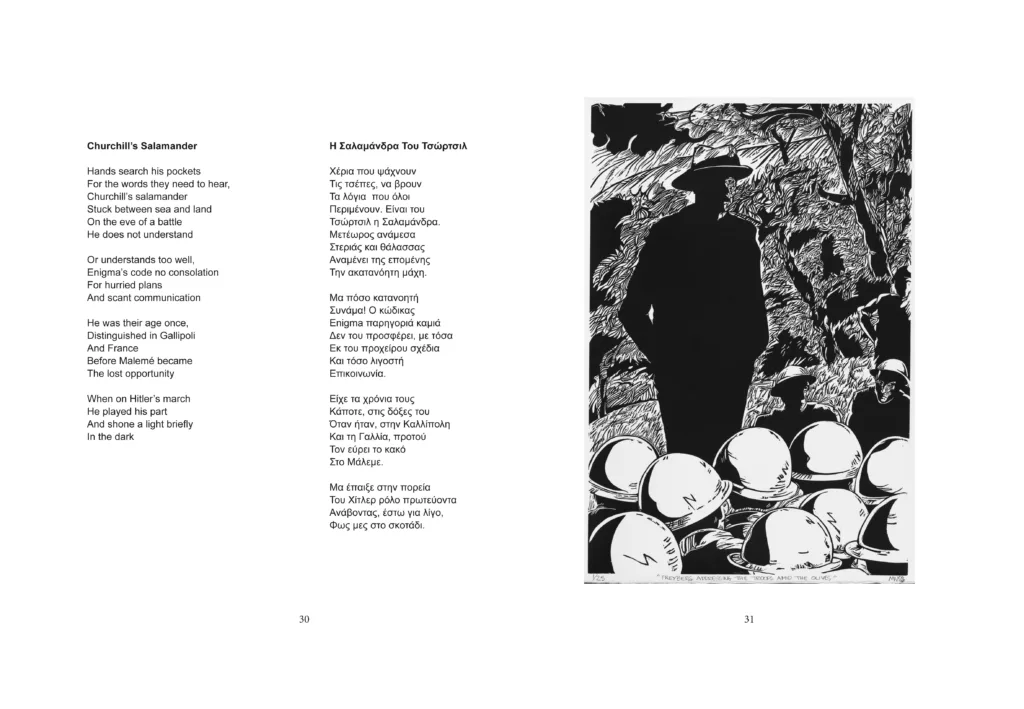

The more stories he heard from locals, the more detail was imbued into his artworks that combine ANZAC military history and Minoan iconography.

“I used the Minoan fresco of a bull as a soldier turned his head angrily towards a German parachuter vaulted over his back to confront him. The bull was trying to toss the soldier off his back, furiously trying to rid Crete of the German,” Michael says.

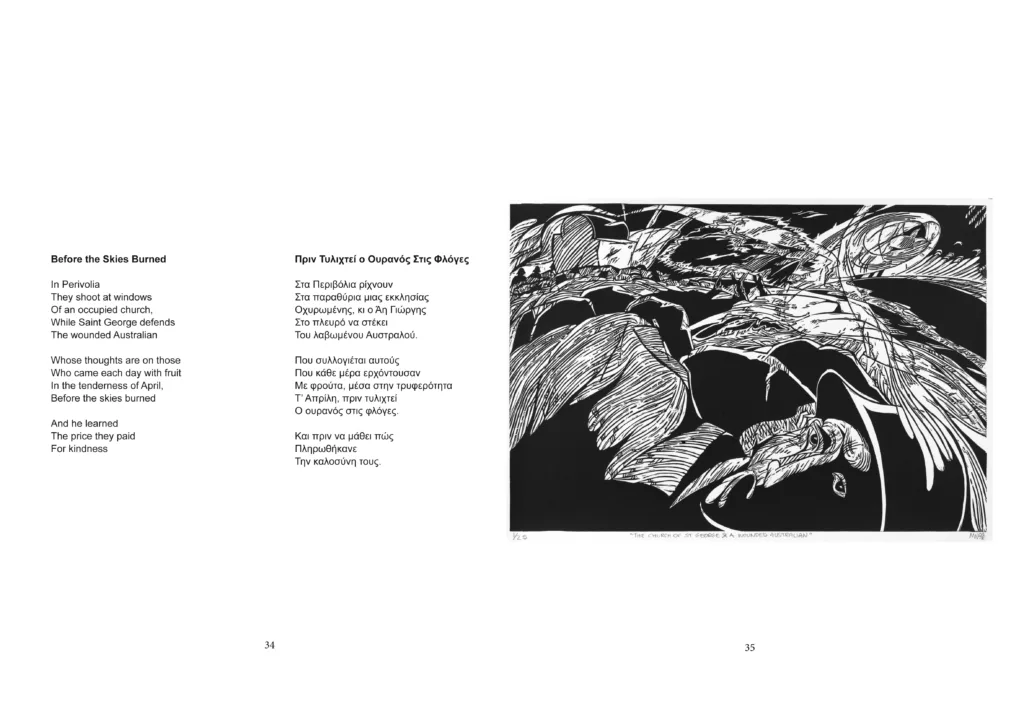

“In another work, I draw inspiration from an archival photograph of a church in Imvros, a village used as a staging post for wounded soldiers. In the photo, the less wounded sat under the shade of a tree, lost in their thoughts. You can see the medics’ cross and the cross of the village church. Two images together with one cross moving and the other standing still.”

He broke the works into stages: arrival, prebattle, evacuation and aftermath.

“The subject is intentionally emotional, and the linocuts are black and white, and very graphic. It had to be like that because of the event and war,” he says. “Poli added the Cretan voice. And I thought that was very important and took the works off in another direction.”

The poetry: Fusions and narratives

Before adding words to the evocative imagery, Poli lived with these 15 linocuts on her wall. Ideas percolated for five years before she got to work producing poetry.

“It was just before lockdown, and the first poem was a birthday gift to Michael,” she says.

One poem followed another in a poignant fusion of poetry and art, paying tribute to the valour and sacrifice of ANZACs and Cretans during the tumultuous Battle of Crete. Scenes of camaraderie, conflict and resilience amidst the Nazi invasion and Occupation stretch back in time to Minoan culture creating symbolism and synergies.

“Visual art deals with a moment at a time. When you write a poem or a novel, language can flash forward, flash back, and make associations. Every time you change a stanza you can go anywhere in time and space,” Poli says.

Through her words, Poli embellished the images, weaving in Minoan iconography. There’s a poem about a young Australian Greek soldier from Melbourne. Born to Greek parents, he had never been to the country of his heritage but for war.

“I imagined him being so close to history and never seeing anything. I imagined how he was planning to visit the palace of Knossos and had hoped to survive. I imagined him looking at the frescoes,” Poli says.

“In another instance, there is the myth of Daedalus and Icarus, and the cutting-edge technology of Germans using their superior aircraft to kill people while Daedalus laments.”

For Poli, the project was not merely an artistic endeavour but a deeply personal journey to honour her ancestral roots and give voice to untold family history.

“The work has been in my head since 1994 when my uncle showed me the memorial and talked about my grandfather, Konstandinos Tatarakis. After that, there was no turning back,” she explains.

Poli already knew the story of her grandfather from her mother. Being in the location where the mass murder of civilians from nine villages took place, however, put everything into focus. The thought of creating a work about war, and using ancient mythology to depict it became even more compelling.

Executed on 22 August 1944, Tatarakis was a member of the Resistance movement. He was killed in the massacre known as the Holocaust of Kedros – a reprisal operation mounted by the Nazis. Following the execution, there was looting, pillage and destruction. Plumes of smoke rose from the villages.

Tatarakis left behind his wife and five children, one of which was Poli’s mother.

“My mother met her first Australians in 1941,” Poli says. “Long before she knew she would migrate to Australia.”

As a young girl, Poli had never really fathomed the link between her own family history and the country she was growing up in.

“I grew up in white Australia, and at school I had never heard of the Greek campaign, which is a pity. At school, my teacher made me change my name because she wouldn’t accept the name Politimi and the rest of my schooling didn’t improve on that,” Poli says.

She says the linocuts bought her desire to pay homage to history to the fore. Poli wanted to right a wrong and shed light on a missed opportunity.

“Growing up, I didn’t realise how close Australians and Greeks had been in the 1940s, and it wasn’t until I wrote this book that I felt my Cretan and Australian sides that had been unnecessarily polarised come together,” she says.

Michael adds that the work is a harmonious collaboration between himself and Poli.

“Poli’s voice brought another dimension and the book is a combination of the two. Me, the Antipodean, and Poli, the Cretan, welding together our personalities,” he says.

“It has a voice. It is bilingual. It can be read equally as easily in Crete as Australia because the voices of Cretans and Australians are the voices this book is credited to,” Michael says of the linocuts combined with the poetry.”

The new book, “Into the Moonlit Village” (Στο Φεγγαρόλουστο Χωριό), is set to be launched at the Greek Community of Melbourne (168 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne) on 9 June 2024. Key contributors are Petros Fournaris, whose translations ensured the poems retained their authenticity, and Frixos Ioannidis, whose editing and design work brought the project to fruition.