By Stamatina Notaras

The memory is vivid. Years ago, I was on the bus home from university reading a book called Being Mortal. As someone who has to talk herself out of an existential crisis once every few weeks, I admit that reading this book put me in the eye of the storm.

In short, Being Mortal takes the reader on an honest and humbling journey of what’s important in life, all the way to its inevitable ending. The key message is that “the ultimate goal is not a good death but a good life—all the way to the very end.” With every word I read, my heart raced, and my arm hairs stood on end as I became increasingly aware of our mortality – sheesh, right? But when I inevitably picked the book back up and reached its final pages, it left me with a few thoughts. First, It forced me to face a few fears, and second, it sparked an inquiry into how different cultures treat their elderly generation.

Culture plays a significant role in how we care for people when they gradually – and then with great force – enter the winter of their lives. The way each culture does so can be closely linked to the traditions and values held highest by their communities. From where I’m sitting, it seems some view the elderly generation, who once lived vibrant, full lives with busy calendars and active homes, as a problem to be fixed, rather than a vital piece of the puzzle, with a place made just for them.

Being born in Australia, yet raised in a Greek tradition, I’ve noticed a clear contrast between Australian culture and that of ethnic communities. A good way to illustrate this is by looking at the Greek and Indian cultures. While both are unique in their own ways, they share a common value: a deep sense of respect for family and an inherent understanding of the responsibility to care for one another.

For Greeks, this isn’t a foreign practice. With most of the elderly generation coming from small villages in Greece where neighbours were family and individual livelihood was a community effort, it’s no surprise that this mentality has persisted across generations. Using my Greek community of Brisbane as an example, elderly members more often than not continue to live as full and vibrant lives as they can maintain. An average week is commonly filled with last-minute drop-ins from family and friends, a healthy sprinkling of community outings, church services with lunch to follow, and monthly outings to waterside destinations.

Aged care worker, Eugenia Theodosiou sees examples of this village mentality in her nursing home regularly. When comparing Greek and non-Greek patients, she identifies the differences in how involved each family becomes in their loved one’s care. Greek families are more vocal in what they expect, regularly checking in to ensure staff are going above and beyond.

As you can probably imagine from watching movies like My Big Fat Greek Wedding and Acropolis Now, Greek families pretty much reside in each other’s pockets. While in your formative years, you beg for moments alone and a path carved separate from your family, the pendulum will swing the other way in decades to come. While some may joke about how peaceful a quieter Christmas would be, yearn for a bit more privacy, or wish for a wedding guest list that could be cut in half, it’s these cultural obligations that keep us alive, thriving, and in constant connection.

Similarly, in Indian culture, respect for the elderly plays a central role in family life. Australian-born Punjabi, Jasmeen Kaur, shares these experiences while remaining open-minded about the difficulties they come with. While Jasmeen holds both respect and love for her traditions, she maintains a healthy inquisition towards their obligatory nature and the necessity for a mindset shift. The strong hierarchical structure that comes with growing up in an Indian household often comes at the cost of the younger generation, who are sitting at the bottom tier.

“My family has always told me to put the elders before myself. I was expected to serve them selflessly. There were times when my cousins and I were expected to care for our grandma’s needs. I never minded this, as I loved her deeply. However, upon reflection and personal growth, I wonder how my responsibilities to her may have inconvenienced my own life – and the realisation that no one was there to care for me,” she says.

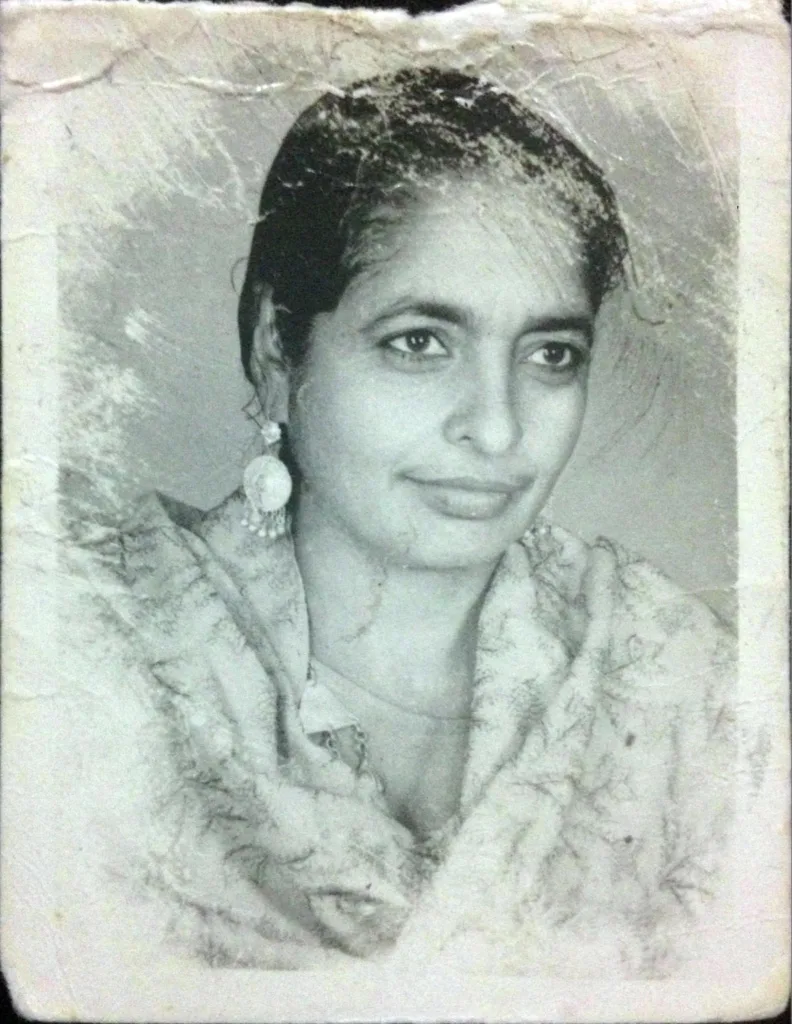

The elderly are not only highly regarded in Indian culture, but are the center around which the rest of the family revolves. Jasmeen recalls visiting her grandma overseas, and as soon as she entered the family home, she would weave her way through dozens of relatives in search of her grandma’s hugs and blessings.

So, the next time you visit your grandparents, put your phones down and let them in on your juiciest life updates. After all, to be mortal is to be alive – wouldn’t you want to relish in it until the very end?