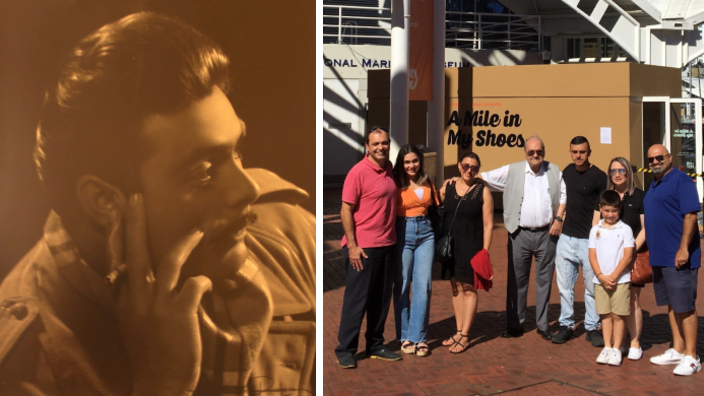

George Alfieris’ migration story was selected by the curators of the UK Empathy Museum to be included in their Australian Mile in My Shoes exhibition which is running at the Australian National Maritime Museum until April 30. George, 88, was the only Greek Australian represented in the 35 migrant stories featured in the exhibition.

This is George’s story in his own words.

“Australia was part of my destiny even before I was born. My father, Emmanuel, migrated to Australia in 1911, with my grandmother, Spryridoula, when he was just 13 years old to join his older brother, Brettos, who came to Australia in 1909. My fate was sealed 23 years before I was born.

Emmanuel and Brettos emulated many of their Kytherian compatriots and established their own business in the NSW country town of Wellington, adding another dot on the Kytherian business map of Australia at the time. They did well and were founding members of the Kytherian Brotherhood of Australia in 1922 making a sizeable donation. By the late 1920s the Great Depression hit their business prospects and Emmanuel, now nearing 30, needed to find a bride. The brothers decided to return home – to Kythera. The stress of the pending return was too much for Spyridoula. She died in 1927 and is buried in an old section of Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney. I visit her once a week.

Emmanuel found his bride when he returned to Kythera. He married my mother, Loukia, an adopted orphan with deep grey eyes. I was born in 1932, their first child, and another son, Theodore soon followed.

READ MORE: Migrant exhibitions celebrated at the Australian National Maritime Museum.

In 1936, Emmanuel returned to Australia to run another business in the NSW country town of Tocumwal. Loukia was pregnant when he left. Emmanuel craved for a daughter and told his wife – “If it’s a girl don’t spare any expense and telegram me straight away. If it’s a boy, you can send me the good news in a letter.”

A telegram was indeed sent announcing the birth of a baby girl, Spyridoula. However, Emmanuel unfortunately wasn’t able to meet her. I remember her illness like a dream, with the neighbourhood women bringing various village remedies. My father would later lament that we were not in Australia where his daughter would have received proper medical care.

A pending war in Europe and extreme loneliness led Emmanuel to once again return to Greece in 1939. My youngest brother, Constantine, was born just as World War II arrived on the island.

I still vividly remember the war. More than anything, I remember the hunger. I also remember my mother’s despair as my father traded the land he bought with the money he earned from Australia for food for us to survive.

READ MORE: ‘A Mile in My Shoes’ exhibition guides Australians through 35 unique migrant stories.

With all the family resources expended, we left the island after the war for the port city of Pireaus, where my father was able to find work with the British army stationed in Athens. However, the British ultimately left, and our family’s path back to Australia was Emmanuel’s only livelihood choice. In 1950, he took my brother, Theodore, and they migrated to Australia and settled in the country town of Hillston, NSW where he bought a half stake in a local café from another Kytherian. In 1952, my mother and Constantine followed. I was at high school at the time and was academically inclined so my parents left me behind to finish my studies.

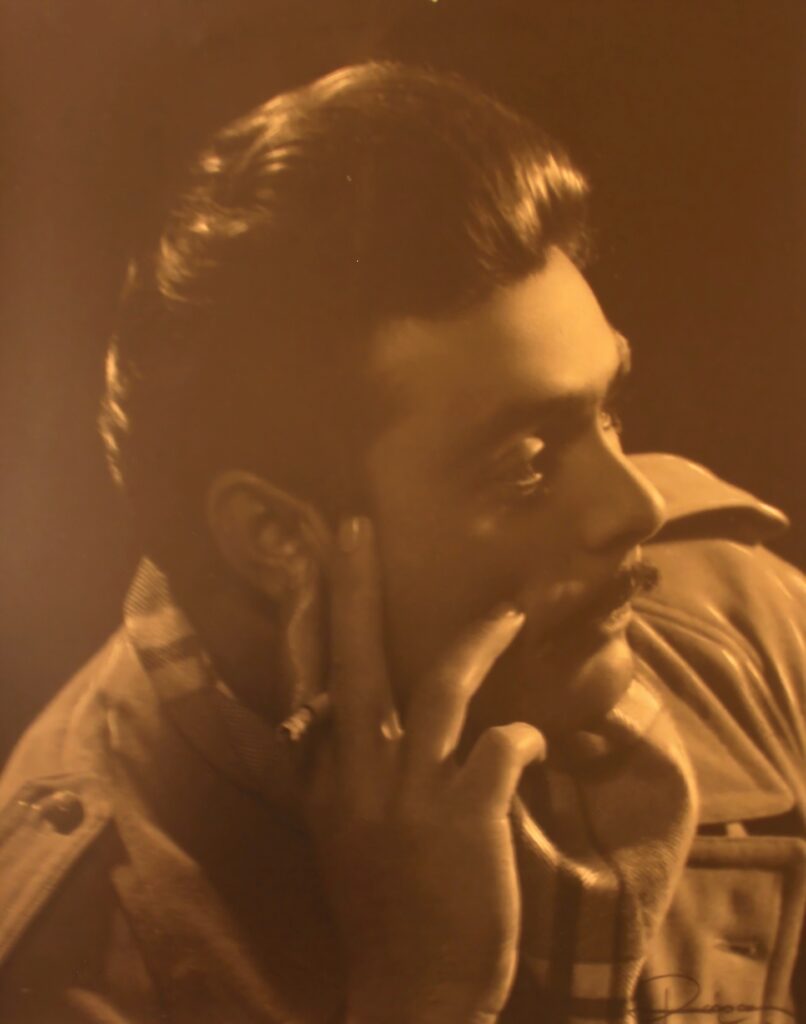

I first saw a motion picture in Pireaus and those black and white stories on the silver screen captured my imagination. After high school, I enrolled in the Athens Cinema School and graduated in 1954 with dreams of being a director in Greece’s fledgling movie industry. However, it became clear that the only way for me to achieve my dream was to fund my own productions. And I would not dare ask my father, slaving away in an Australian country café, to indulge me with such money. So in 1956, aged 24, I boarded the ocean liner Orontes along with hundreds of post war Greek, Italian and Maltese migrants and sailed for Australia.

Within a couple of weeks of my arrival, my father became gravely ill. The harsh Hillston damp winter took its toll and my father died from pneumonia. He was buried with his mother in the same Rookwood Cemetery grave. I visit him every week as well.

Rural country living was not for me. My brothers could not convince me to join as a partner in the café and I left for Sydney to find my future. I settled in the Kings Cross boarding house my father had bought in the 1920s. At the time, “the Cross”, was Sydney’s seedy fringe, but was much closer to the cinema bohemian circles I so missed in Athens.

READ MORE: The ‘Welcome Wall’: A national monument to over 30,000 migrants who moulded Australia.

From an early age I sketched and at high school I would draw the Hollywood stars of the day. If I couldn’t become a movie director, perhaps I could become an artist. So I enrolled at the Sydney Art School and attended night lessons while I worked during the day at the Glass Factory.

Life realities however soon became apparent. I couldn’t sell enough paintings to make a living. So I enrolled in a commercial art course at Sydney’s Technical College. My creative instincts finally found an avenue that would allow me to make a living. I became a printer and worked for over 20 years at John Sands, one of Australia’s largest printing houses at the time.

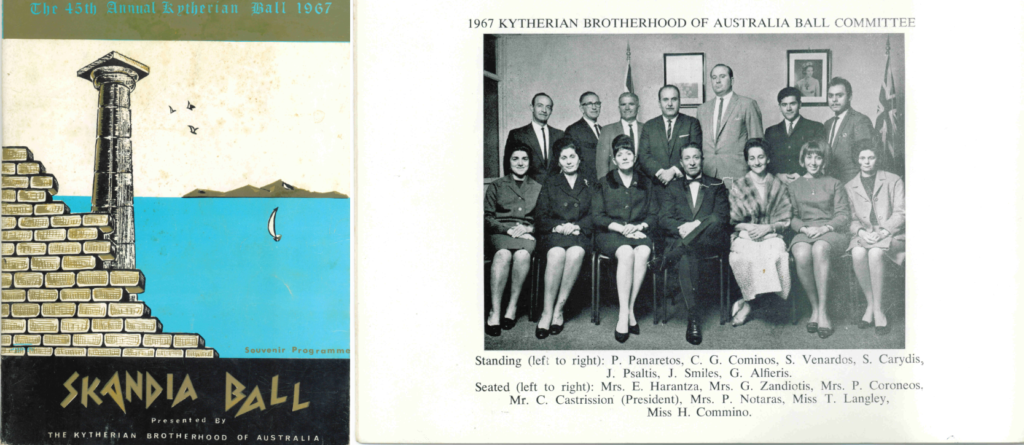

I also volunteered for community organisations where I used my art skills to paint the sets of a thriving Sydney Greek theatre scene and to design the programmes and paraphernalia for the Kytherian Brotherhood Annual Balls.

In the mid 1960s, I met the love of my life. I just didn’t know it yet. Stella was a beautiful kind woman, but I couldn’t see what was in front of me. Perhaps because I had my mind set to follow my father’s footsteps and return to Greece to find a bride. So in 1967, like my father 40 years earlier, I sailed full of anticipation back to Greece.

Soon after my arrival in Greece, my mother told me, “The local butcher has a younger sister, Argentina, she’s 25 and I think you should meet her.” I was 35 and said to my mother that the age gap is too large and it wouldn’t work. However, my mother insisted, “Just meet her and then make up your mind.”

Argentina was a tall woman with striking features and I immediately liked her. We started seeing each other and within a couple of months we agreed to get married and start a life together in Australia. A few days before the wedding I went to arrange Argentina’s passport. It was then that I discovered that she was only 19 years old. I wanted to call it all off. But both families pleaded with me to go through with the wedding. “It’s not such a big age difference,” my future mother-in-law pleaded with me. “Her father and I had 15 years difference and we lived very happily together.”

Argentina struggled with life in Australia. She didn’t know the language, didn’t have any family and was often home alone as I took as many shifts as I could at John Sands to set us up our financially. It was only on the weekends where she and I would meet our friends at each other’s homes or at picnics across Sydney.

In 1969, we had our first child. But the little girl was born very ill and she died within a few days. We named her Spyridoula just like my grandmother and baby sister. Two healthy boys, Emmanuel and Nick, followed in short succession. But Argentina was not happy.

Argentina wanted a new life and left me and the children for a Greek telephone repair man whom she met when he fixed our phone while I was at work. Both I and our friends tried to save our marriage but it was futile. Emmanuel was only 3 and Nick was still in nappies. Our Spanish neighbour, Maria, looked after the boys during the day and they started speaking Spanish. I would try my exhausted best when I returned home from work to look after my sons. These were the most difficult years of my life.

When arranging the divorce my lawyer warned me, “George, you need a woman to take care of the children or else the Judge will put them into foster care.”

That was characteristic of the times. Fathers were not deemed to be capable of child rearing. There needed to be a woman in house.

I pleaded with my mother to return to Australia and help me raise the boys. My mother returned with a heavy heart. She had promised herself she would never return to Australia after my father died. With my mother in the home, the Judge agreed to award custody of the children to me. Argentina didn’t bother to come to the court.

Stella had already returned to Greece a few years earlier. In a frank discussion with a mutual friend I said, “Stella is a good woman. I should have asked her to marry me and not gone to Greece to get married.”

“I got a letter from her the other day George,” my friend responded. “She’s still single. Let me write to her and see if she would be interested.”

Stella was open to the idea and I courted her by correspondence. Stella accepted my marriage proposal. But she didn’t see Australia in her future. She would join me in Australia if I promised that within 5 years we would return to Greece and live our lives there.

The boys loved Stella and called her “mum” from the very beginning. And she loved them as if they were from her own womb. Stella and I had a failed pregnancy that resulted in her having a hysterectomy. But Stella was always positive and filled our family life with love and joy.

I kept my promise. We sold everything and returned to Greece in the early 1980s. When Emmanuel and Nick finished high school at the American College in Athens, they wanted to attend Australian universities so they returned to Australia in the early 1990s.

From then on, Stella and I would follow the summers. May to September in Greece and October to April in Australia. They were blissful years enjoying the best of both worlds and the fruits of our labour. That came to an abrupt end in 2011 when Stella died of cervical cancer from the only part of her uterus that wasn’t removed when she had her hysterectomy. Stella is also buried at Rookwood cemetery. I visit her every week too. One day I will join her and we will be together for eternity.

I now live permanently in Australia and count my blessings. My sons have established themselves with lovely families, successful careers and contribute to our community. I have two wonderful daughters (in-law), something my father was never able to enjoy. My daughters have given me three grandchildren, George, Victoria and Jonathon, who give me immense pleasure and validate my life choices. Australia has given me a “better life” for my family and I couldn’t have asked for a better destiny.”