By Kathy Karageorgiou.

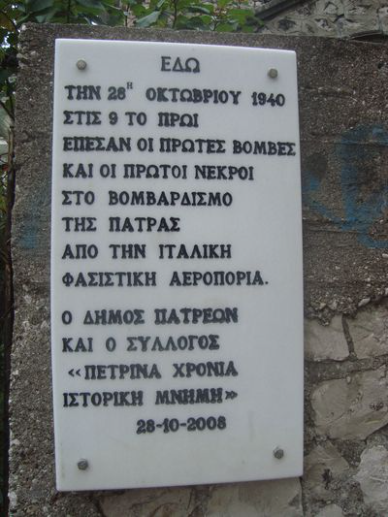

Patras was the first city in Greece to be bombed by fascist Benito Mussolini’s Italian army in the morning of ‘OXI’ (No) Day – October 28, 1940. The response of ‘OXI’ by the then-Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas to Italy’s ambassador was essentially taken as a declaration of war by the Italians and their allies, including Nazi Germany. The ‘OXI’ meant “no” we will not let you pass through Greek territory – and hence be allied with you, nor even neutral, in your war path.

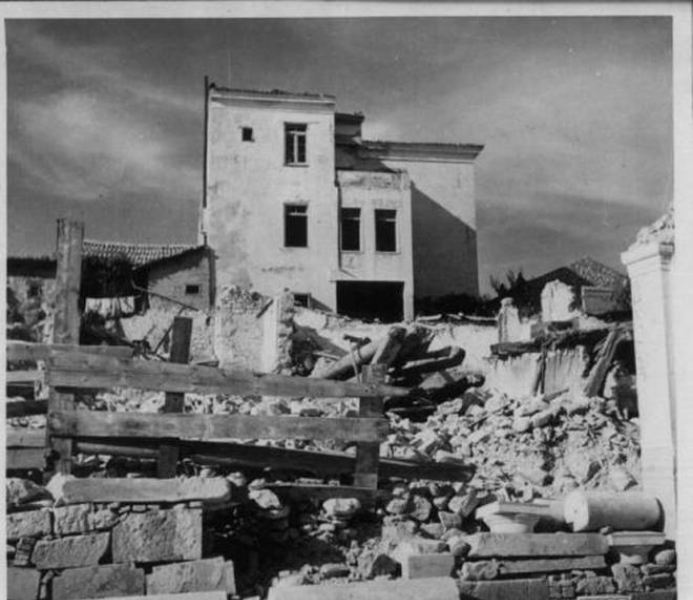

Hours after the ‘OXI’ declaration, an aerial bombing of Patras – Greece’s third largest city (and capital of the Peloponnese) began. This was due to Italy’s proximity to this part of Greece and the major port there. The aim of the Italians was to damage the port facilities of Patras, to prevent Greek troops and military supplies to Northern Greece’s Epirus region, near Albania which Mussolini’s army had occupied.

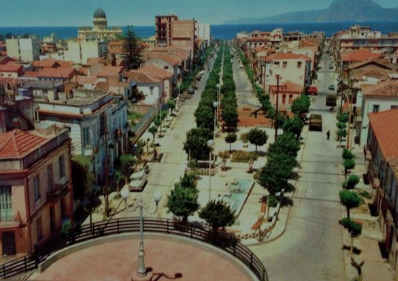

It is said that the Italian army’s air force were aiming for Patras’ port, but were so off target and/or were side tracked by believing they saw Greek soldiers lined up on the ground in Patras ready to fire at them. They thus bombed Trion Navarhon, a long, central street in Patras, but there were no Greek soldiers awaiting the Italian attack on this street. In their Pelargos fighter planes, from their aerial vantage point, the Italians mistook the trees lining this attractive mini-boulevard for the Greek army!

Though 81 years have passed since then, Nana, an 88-year-old woman from the Trion Navarhon area, says: “I still wince in terror and my heart involuntarily races to this day when I hear fireworks or firecrackers during celebrations, such as Greek Easter’s Anastasi night after midnight – because I’m reminded of the bombings.”

Approximately 200 people were killed in Patras from the Italians’ aerial bombings, which included other parts of the city.

Ms Lily Kypraiou, mother of Michalis Kypraiou, has brought up her son on her recounting of the shock and terror of ‘OXI Day’ and beyond in Patras. Michalis, aged 65, knows only too well the horrors of that morning which his mother lived.

“She’d tell me many, many times growing up – and to her death – that in her early teens she and others ran out onto the nearby Trion Navarhon Street to wave, and excitedly applaud the planes flying overhead,” Michalis explains.

He relates that this was before the thunderous bombs began to reign down. In those few moments of innocent and deluded joy, before the “hissing of the bombs, before their crashing onto the ground and shops and houses and people from only 200 metres above, my mother and her neighbours thought it was the Greek air force flying ceremoniously to commemorate our Prime Minister Metaxas’ ‘OXI’ to Mussolini’s government. But then, the inevitable happened – a deluge of whistling bombs, destruction, terror and death.”

Even so, a curious sentiment seems to be part of the popular discourse about Patras’ October 28 bombing and invading forces – the Italian army. That is, that they were “good people.”

Michalis explains: “I recall my mother saying that the Italian soldiers were not so savage, as they’d give food to the starving locals, whereas Hilter’s army (which overtook Patras a few months later) would throw food away in front of the poor and hungry, including children. Also, as children, my mother and her siblings and general neighbourhood, would see fellow Greeks hung from trees by the Nazi forces, close by Psila Alonia square.”

In this context of barbarism, with perceptions of normality affected, the Italian forces seemed ‘good’ and even noble. Michalis also stresses that his mother, after such war turmoil, was always grateful for everything – for the simple pleasures of life such as health foremost, but also a basic meal, or a walk in the Plateia (the local square). He states that many of the people of Patras are like that, with an optimistic and positive life attitude.

“They live in the present, and of course it has a lot to do with the terror of that day on October 28, 1940, in Patras when they thought they were going to be among the dead,” Michalis explains.

Mr Vasilis Thomas, aged 87 and another resident of Patras, tells of the bomb shelters people rushed to on that day.

“Cramped, confused people. Silent or praying,” he says, adding “those who could, went to relatives and friends anywhere out of Patras.”

“For those of us who stayed behind though, we wore a brave face.”

Then, composing himself, he declares, “No. We were brave, and just got on with things, bonding more than ever as a community. That’s why us real Patrini are so bonded and proud to this day.”

“I pass this knowledge and ethos to my son Dimitris; a wonderful man and father who will pass it on to his daughter Angeliki.”

Dimitris, his son, smiles and nods his head, saying: “You know, when I begin to worry about the stresses of everyday life, I remind myself of what the people of Patras went through on that fateful day on October 28, 1940, and beyond – throughout the occupation. We’re talking about starvation. Many selling furniture for a handful of raisins.”

I posit to these Patra residents and interviewees: “Do you think Metaxas made the right decision by saying ‘OXI’?”

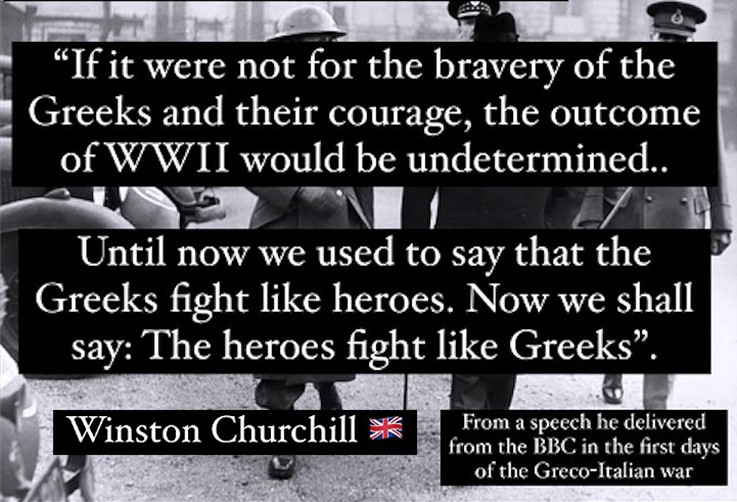

They all say “yes, it was the right decision,” with the general consensus being: “We would have otherwise sold our souls as Greeks; we are a proud people of an ancient culture of philosophy and freedom… we’d have acted as cowards if we didn’t say ‘OXI’.”

Another adds, “We are a democratic and courageous people. For God’s sake, our Prime Minister Metaxas who said ‘OXI’ was a dictator, but even he, a Greek, said ‘no way’ to the fascists and we all backed him. We will, all Greeks will, forever celebrate October 28, as it symbolises our independent spirit and bravery as Hellenes, all around the world!”