From Athens to Australia to the cutting edge of spinal cord research, Melina Haritopoulou-Sinanidou has never taken the easy road. Named the inaugural Woman to Watch at The Greek Herald’s Woman of the Year Awards (alongside her sister Zoe), Melina embodies a unique blend of intellectual ambition, scientific excellence, and quiet resilience.

Her journey began during Greece’s economic crisis, where limited resources clashed with limitless curiosity. A move to rural Australia with her mother (The Greek Herald‘s Melbourne journalist Mary Sinanidis) and sister opened unexpected doors — eventually leading her to a PhD in neuroimmunology and research spanning viral genomics, developmental biology, and cancer immunology.

But her work doesn’t stop at the lab bench.

Melina is also a fierce advocate for equity in science, openly discussing structural barriers in academia, gender bias, and the undervaluation of research careers.

In this exclusive interview, she shares her experiences as a young woman in STEM, the Greek values that shaped her worldview, and the mentors — from family members to scientific leaders — who empowered her to lead with integrity and vision.

Hi Melina, congratulations again on your award recognition. Tell us a bit about yourself.

I grew up in Athens during the economic crisis, when there were significant obstacles in Greece and my family. Limited resources made a scientific career seem impossible for me to pursue. However, my curiosity persisted, and this was fuelled by visits to the local science museum (Eugenides Foundation) and school visits to research institutes across Europe (CERN and Max Planck).

Recognising the need for greater opportunity, my mother was offered a job with Fairfax Media in rural Australia, and we decided to move as a family, a game-changing decision that opened doors to my future. Since then, I’ve seized every chance to excel.

I completed a Biomedical Science degree at the University of Queensland, am currently pursuing a PhD in neuroimmunology, and actively sought out research internships with prestigious labs. Beyond academics, I’m an avid reader and traveller. A gap year solo travelling to Cuba, volunteering at a Costa Rican sloth rescue was chaotic, exciting and unforgettable – a different kind of learning experience, but one that I value just as much.

Moving from Athens to Australia in 2017 must have been a transformative experience. How has your Greek heritage influenced your academic journey, and what values from your upbringing have shaped your approach to science?

I thank Greece, with its broad mandatory curriculum (about 20 subjects), for making me a multifaceted thinker. Secondary education in Greece is chaotic, competitive and sometimes inefficient, but it helped me to take nothing for granted and develop a cross-disciplinary curiosity and questioning mindset that fuelled my diverse research interests.

On another level, you can only survive in Greece if you have resilience, and you need this to survive academia also.

For instance, I am lucky to have a PhD scholarship, which means at least I get paid. How much? About $15 an hour to research spinal cord injury – efforts that could benefit so many lives and save a ton of money in healthcare costs.

That said, I didn’t grow up thinking this was strange. In Greece, it’s not uncommon to work unpaid or underpaid in fields you care about, it’s almost expected. But that doesn’t mean it’s right. It just means I was conditioned not to expect any better.

Here in Australia, the idea of not being fairly paid for your work feels more shocking to most people, and rightly so. Many Australian students are rethinking whether a PhD is worth it, which is part of why numbers are dropping, according to Universities Australia.

Doing a PhD is often a labour of love, sustained by students who are passionate but also struggling to keep up with the rising cost of living. It’s not sustainable, and it’s one of the many things I hope can change about how science is structured and supported.

You’ve spoken about the strong women in your family, including your mother and grandmother, as well as mentors like Professor Vaso Apostolopoulos. How have they influenced your path in neuroscience and leadership?

My grandmother, a teacher, instilled in me a love for learning and a disciplined approach, but showed me the devastating impact of neurological disease. My grandmother’s Alzheimer’s and father’s multiple sclerosis fuelled my drive to understand and combat such conditions.

My mother has been an unwavering supporter, and she taught me resilience and the courage to pursue my passions, even against conventional expectations. Watching her navigate major life changes with strength taught me to embrace uncertainty and take on challenges without fear.

These foundational lessons were amplified by exceptional mentors, and not just women. Dr Sebastian Duchene’s belief in my potential, even as an inexperienced intern at the Doherty Institute, was transformative. He not only taught me crucial coding skills but also recognised my contribution with co-authorship on a publication, a gesture that profoundly validated my abilities and opened doors. This experience reignited my passion for science, reminding me of its inherent problem-solving and discovery.

Professor Vasso Apostolopoulos further shaped my vision, demonstrating the power of translational science and interdisciplinary collaboration. Her mentorship extends beyond academic success; she fosters a supportive environment where students are seen, heard, and empowered. When I faced ethical and systemic challenges during my PhD, she provides not just advice, but a pathway forward even though we are in different cities. These are just some of the people, men and women, who have not only influenced my scientific journey but have also shown me the kind of leader I aspire to be: one who champions others, has integrity and drives meaningful impact.

As a young scientist, you’ve already made significant contributions in neuroscience and viral dataset analysis. Tell us a bit about these.

One of my earliest research experiences was at the Peter Doherty Institute, where I worked on analysing Ebola virus mutation rates across several outbreaks. It was my first exposure to coding and phylogenetics. Despite having no prior experience, I was given the chance to learn on the job. That internship not only helped me build a strong computational foundation but also showed me how powerful genomic data can be in understanding disease evolution and guiding public health responses.

During COVID-19, I was involved in a research initiative by the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, contributing to the Generation Victoria (GenV) birth cohort study by conducting a systematic review on how breastfeeding is assessed in longitudinal studies. I identified gaps in current approaches and recommended ways to standardise data collection.

At the Institute for Molecular Bioscience, I investigated the mechanical forces involved in neural tube formation using quail embryos. This combined molecular cloning, cell culture, and confocal imaging and was my first hands-on introduction to developmental biology and wet lab techniques.

My Honours Research took me into cancer immunology where I investigated whether a proteasome inhibitor could help reverse resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitor could help reverse resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma. What made this project meaningful was seeing the treatment work on animal models. This success reaffirmed my commitment to research. However, on a personal level, it was a challenging time for me as a student because I got to experience first-hand the long hours, high pressure, and blurring of work-life boundaries academia is notorious for.

In addition to this, I’ve worked on literature reviews, both through my collaboration with Professor Apostolopoulos and with a long collaboration with the Mater Research Institute in Brisbane.

Currently, my PhD in neuroimmunology utilises cutting-edge spatial transcriptomics to study spinal cord injury, aiming to identify new therapeutic targets. My interdisciplinary approach allows me to tackle complex problems and translate scientific discoveries into real-world solutions. New approaches excite me, and I feel the field urgently needs to move with the times.

As you can see, I have not committed to a single niche early on. I’ve chosen projects that excite and challenge me, and through each one, I’ve grown both technically and intellectually. My core motivation is to learn, to ask meaningful questions, and to contribute to science that has the potential to make a real difference in people’s lives.

What challenges have you faced as a woman in STEM, and what advice would you give to young women aspiring to enter the field?

While academia poses universal challenges, gender adds layers of complexity. My experience contrasts sharply: Greece’s traditionalism demanded exceptional effort from women in STEM, forcing me to seek opportunities elsewhere. Australia’s progressiveness offers open dialogue and systemic change, yet, despite a more progressive mindset, biases persist.

Ironically, some of my toughest challenges stemmed from women perpetuating stereotypes – relying on charm over competence. I’ve worked alongside women who use their gender to get that “extra help”. For instance, I had a colleague who has said, “I’ll talk to the boss, he can’t resist my smile.” While this might seem harmless on the surface, it plays into long-standing stereotypes that women are less capable or more emotionally driven, better suited to being agreeable than assertive. And that, in turn, impacts how the rest of us are perceived.

When I try to be assertive or take initiative, I’ve found I’m more likely to be labelled “difficult” or “intense,” whereas a male colleague showing the same behaviour is often seen as a natural leader.

When women lean into stereotypes to their advantage, it can also create tension within teams. It undermines women who are working hard to lead with professionalism, and it sends the wrong message, that being strategic means using gender, rather than skill, experience, or insight.

Of course, the issue isn’t just gender, it’s also about how leaders navigate power, responsibility, and respect in the workplace.

My advice? Regardless of the situation, focus on integrity and hard work. Be assertive, analytical, and authentic. Science needs your genuine talent, not a smiling vulnerable persona. Find supportive mentors and, in turn, uplift others. Ageism and rigid hierarchies can be daunting, but your unwavering commitment to excellence will ultimately earn respect.

Your work in neuroscience goes beyond research—you also create ‘art with cells.’ Can you share more about the connection between science and creativity in your life?

The phrase “making art with cells” honestly makes me giggle a little, because this is actually a core part of my research.

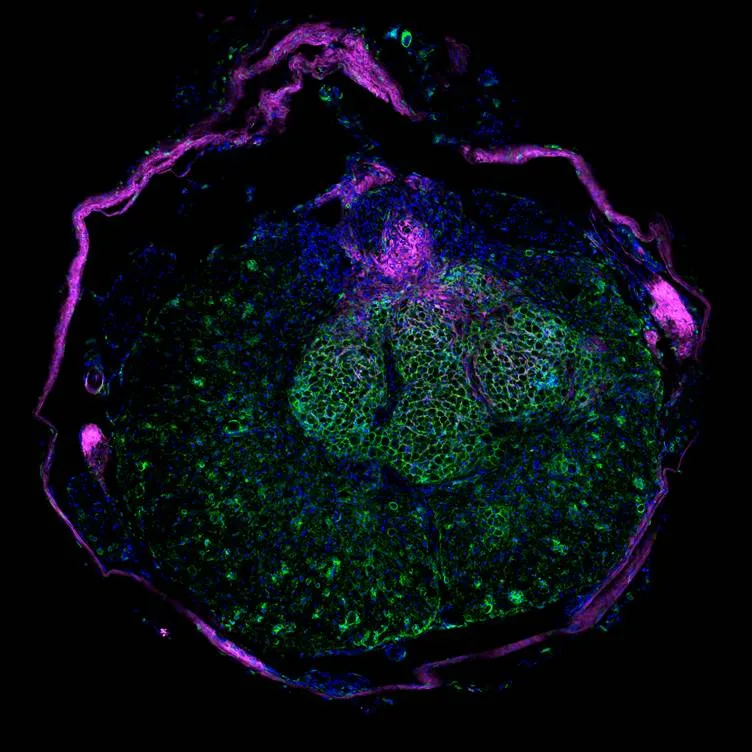

For my PhD project, I use histological techniques to study how different cells and structures behave following spinal cord injury. To put it simply, I collect organs from the mice in my study and use antibodies that bind to specific targets, like immune cells or extracellular matrix proteins. These antibodies are tagged with fluorescent markers, which allow me to visualise the location and activity of these targets under a microscope.

These images, while beautiful, reveal critical insights into immune responses and tissue healing. For example, this image shows a spinal cord section from a mouse taken 42 days after a spinal cord injury. The blue stain marks all the cell nuclei, giving a general sense of where the cells are located, and the green shows. This process blends precision with visual storytelling, proving that creativity isn’t just aesthetic; it’s fundamental to scientific discovery.

I think creativity is an essential part of science, not just in how we communicate it, but also in how we design experiments, solve problems, and interpret what we see. Histology, in particular, is one of the techniques I enjoy the most because it lets me combine precision, visual storytelling, and analytical thinking. In a way, it feels like science and art working hand-in-hand.

Receiving the inaugural TGH Woman to Watch award is a significant milestone. What does this recognition mean to you, and how do you hope it will inspire other young Greek Australian women?

I have previously received academic awards related to my work in science. This award is important to me because it transcends mere academic recognition; it’s a powerful validation of my identity as a Greek Australian woman in science. While imposter syndrome often whispers doubts, this moment shouts possibility.

When I accepted the award, I was especially inspired by the inclusion of women like Chanel Contos and Stefanie Costi, who have used their voices to challenge the status quo and drive real change. Even though they weren’t present at the event, their inclusion in the program reminded me that transformation isn’t just possible, it’s inevitable when led with courage and conviction.

To me, this award is more than a milestone, it’s a platform. I see it as an opportunity to connect with likeminded people, like Varvara Ioannou and others who are using their influence for good. I want to learn from their journeys, build meaningful collaborations, and channel what I learn into creating positive change within academia, where structural issues still persist. If I can help spark that shift and show other young Greek Australian women that their voice, their background, and their ambition belong in these spaces, then this recognition becomes something much bigger than myself.

With one year left in your PhD and an impressive research portfolio already, what are your aspirations for the future? Where do you see your work making the biggest impact in the years to come?

With a year remaining, my PhD has presented a stark reality check. My initial dream of traditional academia (postdoc, lab head, professorship) has been challenged. While I deeply love the scientific process, I’ve witnessed systemic issues that hinder genuine progress: excessive competition, pressure for rapid results over rigorous research, and political manoeuvring overshadowing knowledge advancement.

Despite these challenges, I haven’t turned away from academia. My passion for research is still very much alive. But as I move forward, I want to do so with a clearer understanding of how to navigate the system without compromising my values, so that science can truly serve its purpose: solving real-world problems. My goal is to contribute to a more honest, collaborative, and impactful scientific landscape. I’m optimistic, knowing many share this vision.

Is there anything else you’d like to say?

I believe that the most meaningful scientific progress comes from collaboration. I’m always eager to connect with fellow researchers, mentors, and others who are passionate about driving positive change in science. If you share similar interests or are interested in supporting or collaborating on research that aligns with my work, I’d love to hear from you. Feel free to connect with me on LinkedIn. I’m always open to new perspectives, partnerships, and opportunities to work together toward research that makes a real impact.