By Ilias Karagiannis.

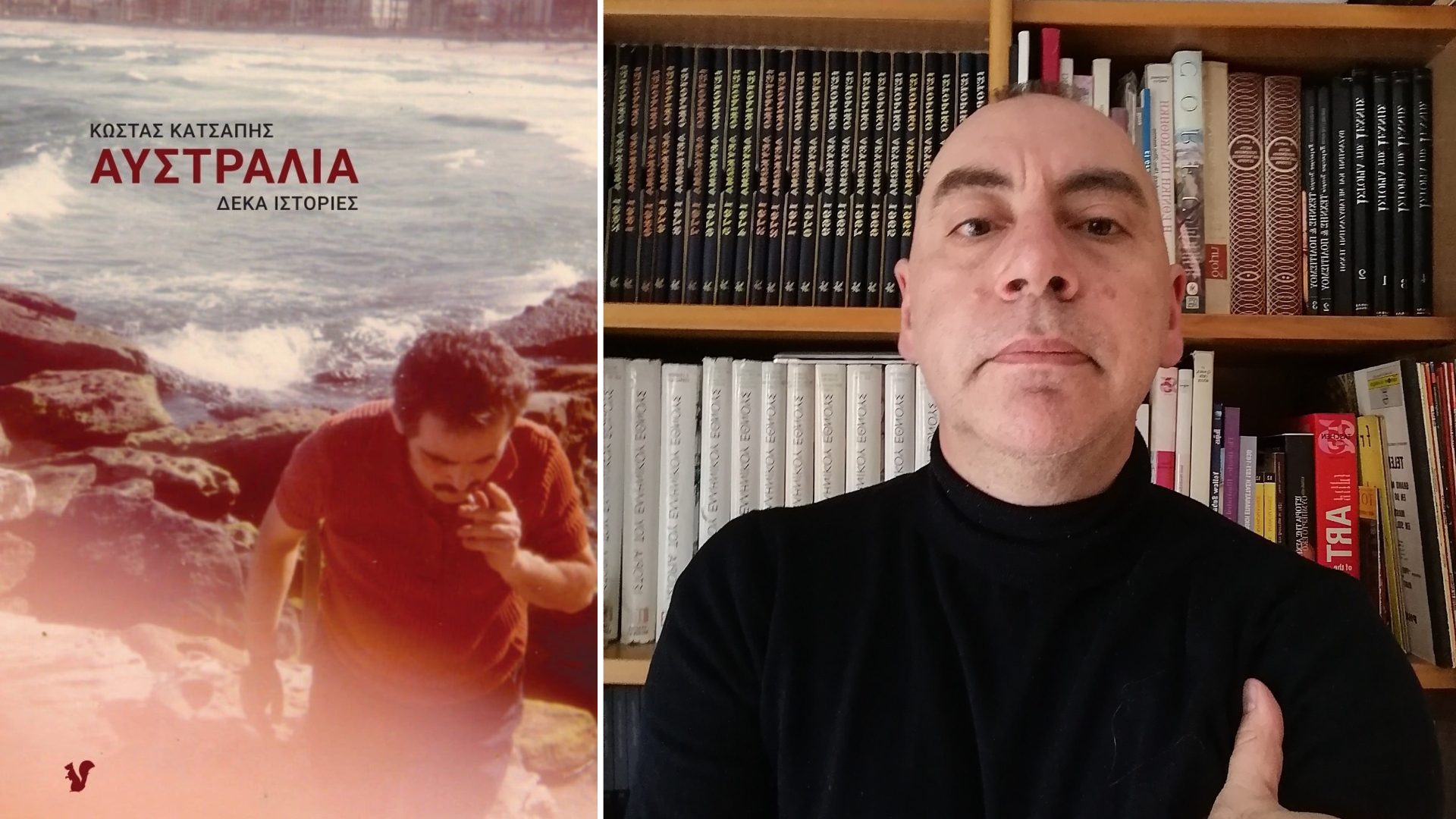

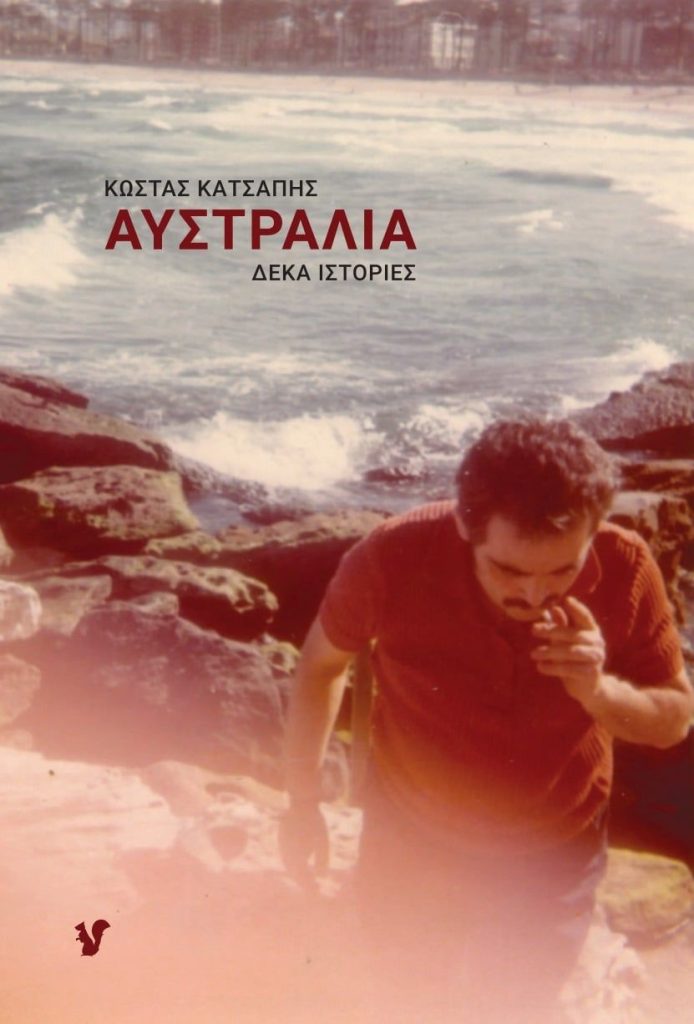

The book Australia: Ten Stories by Kostas Katsapis is a mosaic where hope, dreams, fear of the unknown, emigration and of course, immigration are interlinked.

The Professor of Cultural History at Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences in Athens, Greece tells The Greek Herald he wants his new book to be a “mosaic of Greek Australian migration, bringing to the fore different voices, and therefore different perceptions, of this defining experience.”

Australia for Kostas, whose parents left the Antipodes in 1972 a year before he was born in Athens, was a “lifeline.”

In this collection of 10 stories, the problems faced by immigrants in the 1960s as they arrived in Australia on ships such as the Ellinis, Australis and the Patris are illuminated.

“First of all, I would like to thank you warmly for your hospitality and through this interview, allowing me to send a warm greeting to our compatriots who are in Australia,” Kostas tells The Greek Herald.

“The ten stories balance between the real and the imaginary. However, contrary to what we believe, many times the “real” is socially and historically constituted so its “authenticity” is checked, while the “imaginary” echoes truths that the documentation finds difficult to serve.

“In the book I paint characteristic types of immigrants, who are “imaginary,” but at the same time they are a synthesis of real persons, or persons who could be based on historical and social conditions.

“Although the plot is mostly a product of fiction, it responds – to be precise – to the problems and situations faced by immigrants coming to Australia. At this point, which is crucial, historical editing has a special weight and is the bet I set myself.

“It is not easy to construct characters that correspond to the historical conditions of another era. In other words, the book is in its own way “true” as it incorporates the feelings and ways of thinking of people of an era that is very different from ours.”

‘Australia is synonymous with hard work’:

Kostas has visited Australia twice and even extracted material from sources such as the historical archive of the Greek Orthodox Community of New South Wales. As we discovered facts about the book, the question arose about its connection with the country.

“My parents were immigrants to Sydney, where they married in 1965. My sister was born in this city in 1966 and in 1972 my parents returned to Greece. A year later I was born in Athens,” Kostas explains.

“As you can see, family memories from Australia are very intense, and I still have relatives, uncles and first cousins in Sydney. I especially love this country. For my family, Australia was a country synonymous with hard work, but it was also a lifeline from Greece’s difficulties.”

We wonder what the author’s goal was while he was immersed in memories and sources. Perhaps it was to be the guardian of historical memory for a phenomenon, migration, that has not been thoroughly recorded?

“When I started writing the book I wanted to write a history book in a different, purely experimental, way. Outside and beyond the commitments of formal, academic history. The reason I decided to choose this method is because through fiction you can talk about things that in a strictly academic text you cannot approach,” Kostas says.

“As I said before, my goal was to create a mosaic of Greek Australian migration, bringing to the fore different voices, and therefore different perceptions of this defining experience. It should be said here that the experience of emigration was not common to all.

“For some it was liberating, for others it was excruciating. I was interested in illuminating this very plurality, which is why the heroes of the book seem to stand in a different way against the great problems of the time or themselves and their families: some want to return, others do not.

“Some want to continue the political struggle in the Antipodes and others to put political passions aside and make a fresh start. Of course, in these conditions, things are not exclusively white or black, on the contrary they depend on the person, his experiences and his expectations. And of course, one is the perspective of women with their own specific problems, and another of children who had to balance between two often conflicting identities.”

Kostas’ love for Sydney:

In Kostas’ previous book The Damned, he dealt with the 1960s. We wondered what attracted him to this period given he was not even born then.

“Your question is very good, but I confess I have no answer yet. Certainly in the science of history it is not necessary to have experiences in order to have a special relation to a period. Certainly, I have always been particularly drawn to the sixties, perhaps because I recognised in it the roots of my identity,” he says.

“The sixties is a time of many contradictions but it is governed by the optimism of a better tomorrow, which is difficult to meet in other times. It is definitely a flexible era, between the “old ” world and the modern one and this makes it very special. Certainly this is all in my own opinion, for others the sixties may be a dull or even unbearably dull period.”

Concluding his interview with The Greek Herald, Kostas revealed to us his love for Sydney.

“I have visited Australia twice, and both times I was hosted by my beloved relatives in Sydney. It is an amazing city with warm and happy people that is worth visiting even time,” Kostas concludes.

“I especially like the sense of multiculturalism that exists is everywhere: in food, in shops, in the neighbourhoods. I especially love the centre of the city and if I could be beamed there I would like to be at the Queen Victoria Building having a coffee. I hope at some point this will be possible.”

READ MORE: ‘In search of a better life’: Con Emmanuelle’s new book tells the Cypriot migrant story.