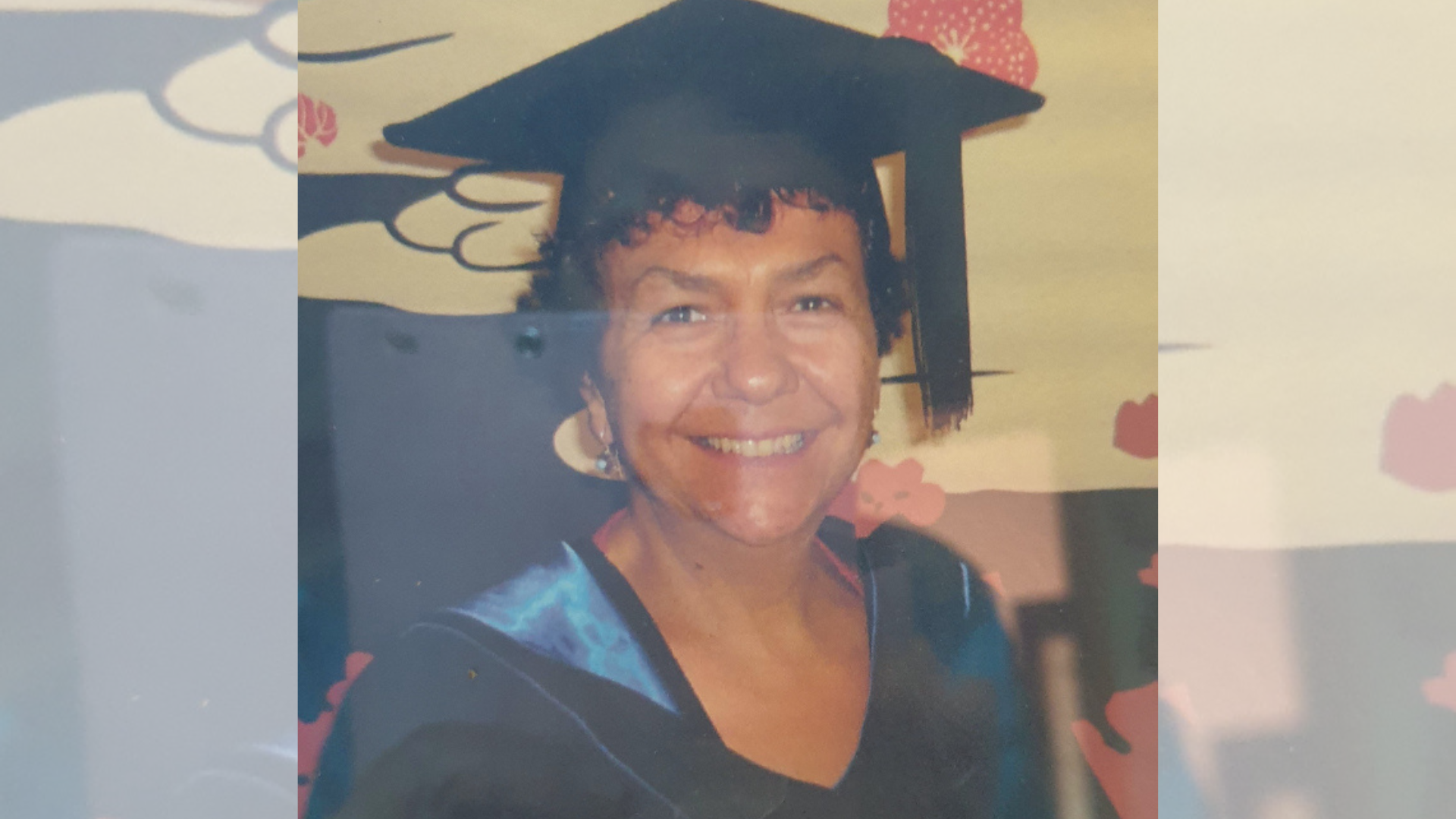

Melissa Afentoulis was contemplating retirement after accomplishing a lot in her extended community services career, however, decided to embark on a PhD in Arts at the University of Melbourne instead.

This is where she soon realised that her life’s hopes and dreams had “come to fruition”.

Beginning early in her career as a social worker who helped to develop a new migrant resource centre, and acting as the CEO of a women’s health organization, Afentoulis found it wasn’t easy to retire after still feeling she could give so much from her experiences.

“When you’ve been working continuously all of those years, in both enjoyable and challenging roles, you can’t just stop,” Afentoulis says. “I look back and think, ‘How did I ever do all these things?’”

Afentoulis, the child of working-class Greek immigrants, came to Brunswick from the island of Lemnos at the age of nine. She became the first member of her family to attend university when she enrolled in an undergraduate program at the University of Melbourne.

Regularly going back to Lemnos over the years, she realised something interesting: the increasing numbers of younger people who were born in other countries but still returning to the home country of their parents and grandparents.

“Whereas I was born there, and I had an existing connection, [they] were coming back for their holidays and not just loving it, but really making a connection that they had never had before,” Afentoulis says.

Afentoulis shared her views with a couple she met at a dinner party, who inquired whether she had considered pursuing a PhD on the subject. She chose to apply after being inspired by their belief in her.

“I wrote a proposal. I wasn’t sure if it was on the right track, nor did I really know what starting a PhD involved. Not only was I accepted, but they offered me a scholarship!”

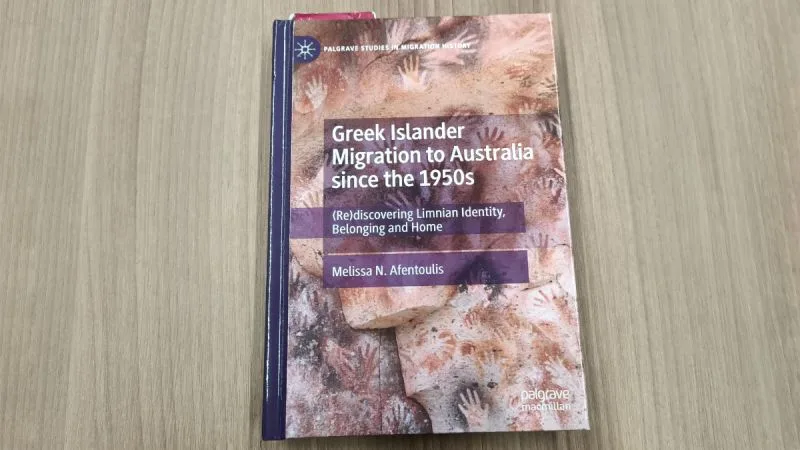

Afentoulis’ PhD sheds light on late-twentieth-century Australian immigration experiences. She implemented oral history to investigate how migration shapes identity and belonging while simultaneously influencing migration.

Her study, she believes, has raised awareness of Lemnos identity and established parallels between their experiences and those of immigrants in general, particularly those who came to Australia after the war.

“There are three cohorts in my oral history data,” Afentoulis explained.

“There are the first-generation immigrants, then there’s the second generation – the children and grandchildren of that cohort – and there are those who didn’t leave the island. They’re the three groups that interact.”

Afentoulis’ supervisor, Professor Joy Damousi AM also has a Greek background and is an expert in oral history and migration history.

“Our relationship was pretty pragmatic. She would give me the framework and I’d go back to my desk and think ‘what do I do now?’ But she had faith in me. When I reflect, I couldn’t have had a better supervisor.”

Afentoulis claims that her study has not only given her academic fulfillment, but also had a major influence on her personal life.

“At a personal level, it was part of the connection I had made back to my homeland myself,” she says. “I wanted to see it through the eyes of others.”

Source: The University of Melbourne