Peter McIntyre was 31-years-old when he decided to join the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in London, who looked to join the Greek and Australian forces in repelling the German invasion on the Greek island of Crete.

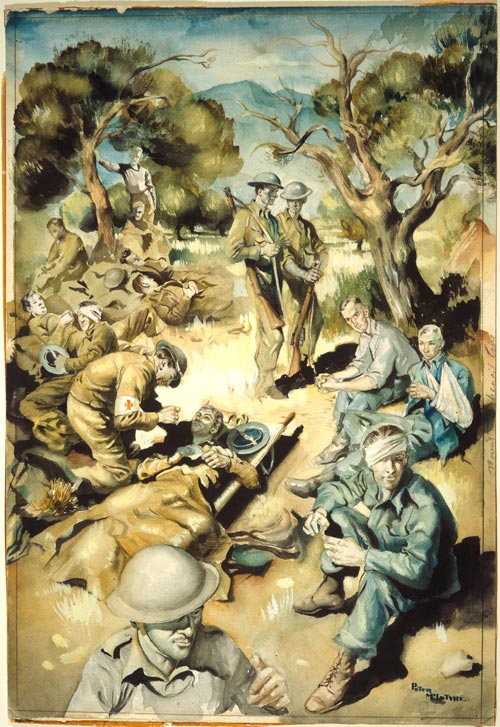

Peter McIntyre quite literally ‘paints a picture’ of what fighting the Germans on Crete was like in his collection of tragically beautiful artworks, which tell a story themselves.

However, in order to understand McIntyre’s journey even deeper, The Greek Herald spoke with the legendary war artist’s daughter, Sara McIntyre.

War through the eyes of a painter

Although born in the New Zealand city of Dunedin, McIntyre studied art at the Slade School of Fine Art in England. In the outbreak of the Second World War, McIntyre was unable to join the British army, instead enlisting in the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force (2NZEF) that was being raised in London.

McIntyre was sent to Egypt where his art skills gained the attention of Major General Bernard Freyberg, New Zealand’s seventh Governor General who became a famous WWI and WII war veteran. Recognising his skills with a pencil, Freyberg appointed him New Zealand’s official war artist.

According to historian Jennifer Haworth, McIntyre remained in Egypt during the Greek campaign, but eventually made his way to Crete following the disastrous result on the mainland. It’s here where McIntyre documents his war journey through sketches, as well as in his book, Peter McIntyre: War Artist.

“At the end of the war on a return visit to Crete I visited this same house and a weeping woman told me how when we retreated, the Germans shot her husband because we had used her home,” McIntyre writes, speaking about a house he once took shelter in after being pinned by German sniper fire.

“In one Cretan village I visited they had lined up all the men, 11 of them, and machine-gunned them down on the suspicion they might have sheltered a New-Zealander.”

McIntyre’s book tells more tales of the disastrous Cretan campaign. The artist notes that he didn’t have much time to create large paintings due to always being on the move, drawing small sketches instead. McIntyre transferred his sketches into larger designs once back in Egypt.

“We had little artillery, some French guns without proper sights, and practically no transport,” McIntyre said in his book.

“We had no air cover. It was no way to fight a difficult battle, and yet we very nearly won.”

“That is the tragedy of it.”

McIntyre’s Legacy

Sara McIntyre grew up most of her childhood life never seeing her father’s war paintings, which were kept in archive storage. After her father’s war book published in 1981, an exhibition of his war paintings was shown for the first time since the war in 1995. This was also the year her father passed away.

Sara said she journeyed to Sfakion with her children in 1977, not knowing that her father had been to the same town, which he regards in his book as the “luckiest place on earth”.

“In Sfakion i went to a taverna. The men were all sitting outside in traditional clothing and they nodded and smiled,” Sara said to The Greek Herald.

“I was traveling with my twin sons who turned four that day. I said, ‘Papa? Nea Zelandia. Kraut’ and did a throat cutting gesture.”

“The men cheered and raised their glasses. It was drinks all round and my boys were fed.”

“I have certainly felt a connection to Crete ever since.”

Sara McIntyre upholds her father’s artistic legacy through the digital lens of a camera, shooting New Zealand’s picturesque landscape.

“With my own work, my father talked about the landscape, the light, all the time. I took such conversations for granted but now realise how much he influenced how I look at scenes,” Sara said.

“His war paintings and drawings tell a story. My photography is often to tell a story. He gave me an appreciation of landscape and people.”