“You are all awesome, and I love you as you love me,” said Greece’s Deputy Foreign Minister Ioannis Loverdos, visibly moved during a warm welcome at the Greek Community of Melbourne (GCM).

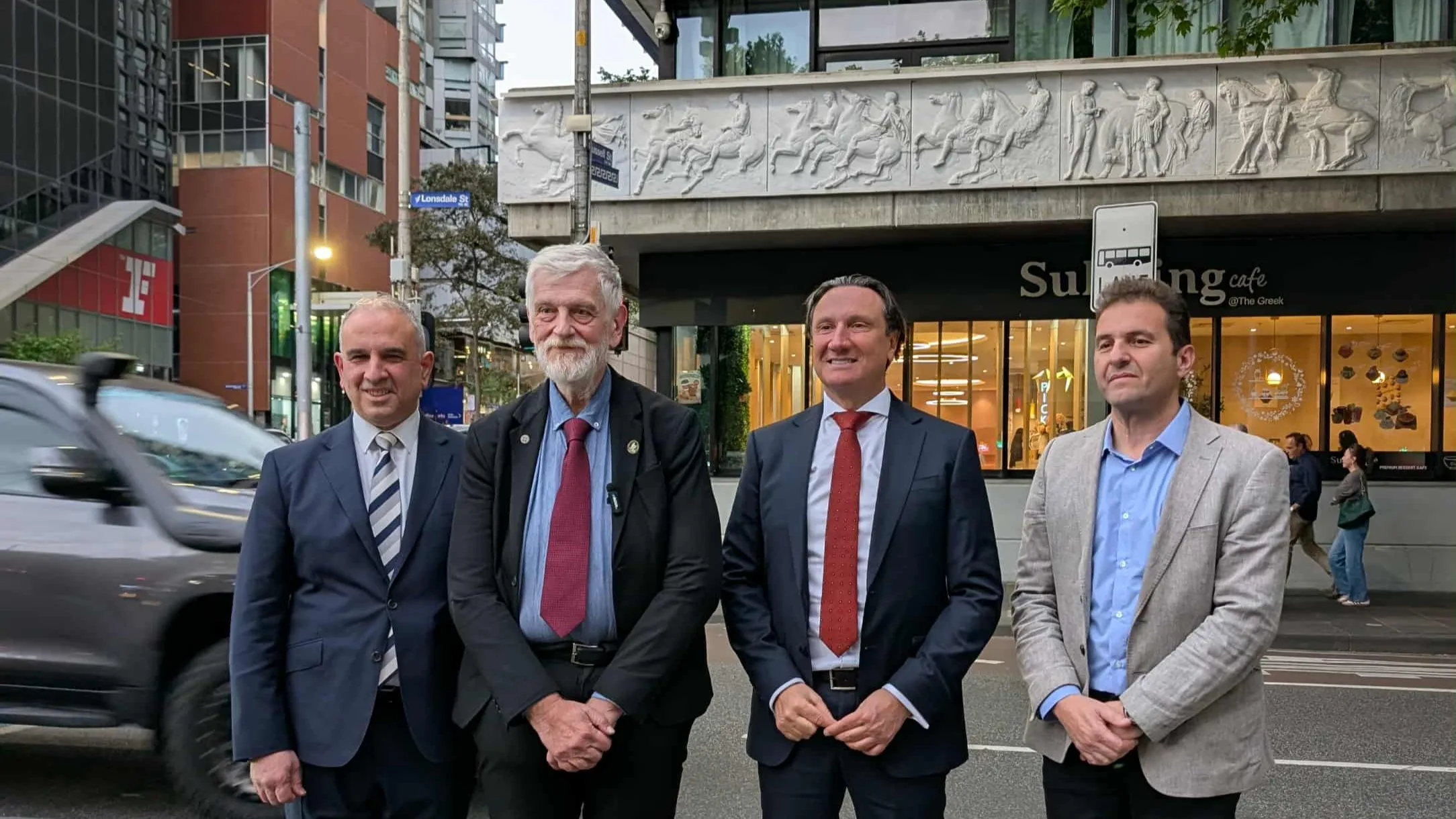

With crowds lining up for selfies and handshakes, it was just as well that Loverdos arrived early at the Greek Centre, giving GCM President Bill Papastergiadis time to offer a tour. Papastergiadis even stopped traffic with his hands as they crossed Lonsdale Street to admire the replica of the Parthenon marbles frieze adorning the building’s exterior.

At the function in Loverdos’ honour, Papastergiadis highlighted the cohesion of Melbourne’s Greek community. “The most important thing about our community is that we are united, with the Church, our associations, media, and those who provide care and welfare. Together we work to leave something better than what we found.”

Loverdos nodded in agreement: “I was very touched when Papastergiadis said the community is united. Sadly, that is not always common among Greeks abroad. But unity is our strength. Greeks and philhellenes must stand together for the great values that Hellenism represents, from ancient times to today.”

Battling jetlag but buoyed by affection, Loverdos added: “I don’t care about business; I care about the feelings you showed me. You made me proud to be here as a Greek, as a representative of the Greek state. You are all awesome, and I love you as you love me.”

He reminded the audience that Greece’s essence transcends geography: “Greece is not only Athens or Thessaloniki, not only Mykonos or Santorini. Greece is a civilisation going back 35 centuries of philosophy, medicine, theatre, democracy, and liberty. And you are the bridge between this civilisation and today’s Australia.”

After official photos were taken, Loverdos urged everyone to sing the Greek national anthem, even Julian Hill, Australia’s Assistant Minister for Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs, hummed along.

Hill lightened the mood with a story about his Greek and Turkish staffers: “Despina, my office manager for the last seven or eight years, was Greek. She shared an office with my campaign manager, Dillon, a Turkish guy. They had the Turkish and Greek flags, and got on peacefully, as we do in the modern era.”

He laughed, adding that part of the deal was for his Greek staffer to spend six weeks a year in the islands. “I did enjoy my own 50th birthday there, Milos, Sifnos, Athens and the smaller islands. I couldn’t imagine our city without the contribution of Greek Australians in every facet of life.”

Beyond hugs and hymns

Before the cocktail function, the Greek Deputy Minister and his delegates, Ambassador of Greece to Australia Stavros Venizelos, and Consul General of Greece in Melbourne Dimitra Georgantzoglou met privately with community leaders. They discussed cultural and educational collaborations, including youth camps and other partnerships.

At the same time, a separate citizenship information session downstairs stirred passionate discussion. Secretaries-General of the Ministry of the Interior, Athanasios Balermpas and Dimitrios Karnavos, and the Head of the Directorate-General for Citizenship, Katerina Ouli, outlined plans to simplify the citizenship process through a new online registry for Greeks abroad.

Ms Ouli said: “We are here to listen and inform you about ways to acquire citizenship, and of course, to hear about the problems you face. Many of you are already Greek by right of birth, but your citizenship has not been certified because marriages or births were never registered.”

Attendees raised concerns about poor translation services and Greek-only websites such as gov.gr. One Kastellorizian woman, frustrated by the lack of English, prompted Balermpas to ask, “If you want to be a Greece citizen you have to speak Greek? How can you read the Greek ballots?”

He later clarified: “The reason I am here is to have this feedback.”

Balermpas said English and two other languages, including French, would be added to the system, though no time frame was given. He also addressed confusion around different names in Greek and English documents: “It’s better to have one name for both countries. It’s not illegal to have two, but one is better.”

When asked by The Greek Herald about Greeks without citizenship who wish to feel Greek, not tourists, when visiting Greece, Balermpas revealed: “We had studied the idea of a ‘Homogeneis Card’ for people who don’t want full citizenship but wish to have Greek status, to open accounts, get low museum prices, and stay as long as they like. It was never implemented, but I intend to raise it again because it’s a good idea.”

As discussions wound down, one thing was clear: Melbourne’s Greeks remain deeply engaged with the future of Hellenism and its Greek politicians.

“You are a living piece of Greece,” Loverdos told the crowd. “No matter the 17,000 kilometres that separate us, in our hearts that distance does not exist.”

The evening ended with Loverdos receiving a plaque and the lasting affection of a diaspora still defining what it means to be Greek in Australia. Distance is sometimes not geographical but lies in the complexities of translation between language, generation, and dual identities: an evolution of who Greek Australians are.

*All photos copyright The Greek Herald / Mary Sinanidis