By Ilias Karagiannis.

Bravery can surface in the darkest time. Look at the people who live today in Ukraine, Israel and Gaza. They are facing dark times like those experienced by the Greeks during the Turkish occupation – in the period of the proud ‘No’ in 1940.

At that time, Olga Stamboli lived in Athens, Greece. She arrived there from Australia in 1936. She was an unemployed actress, penniless, with few friends and a sense of shame that followed her from the other side of the world.

Her acting ability, her knowledge of foreign languages and her character pushed her, without realising it, to become a member of the Greek Resistance at a time when the country entered the Second World War.

When the Germans occupy Athens, Olga continued to rescue British airmen and sabotage enemy supply lines. Until the day she was arrested.

Through the narratives of the mother and her children, we are transported back to the events that marked the two countries, the life of Olga in Greece and her family in Australia from 1916 to 1943.

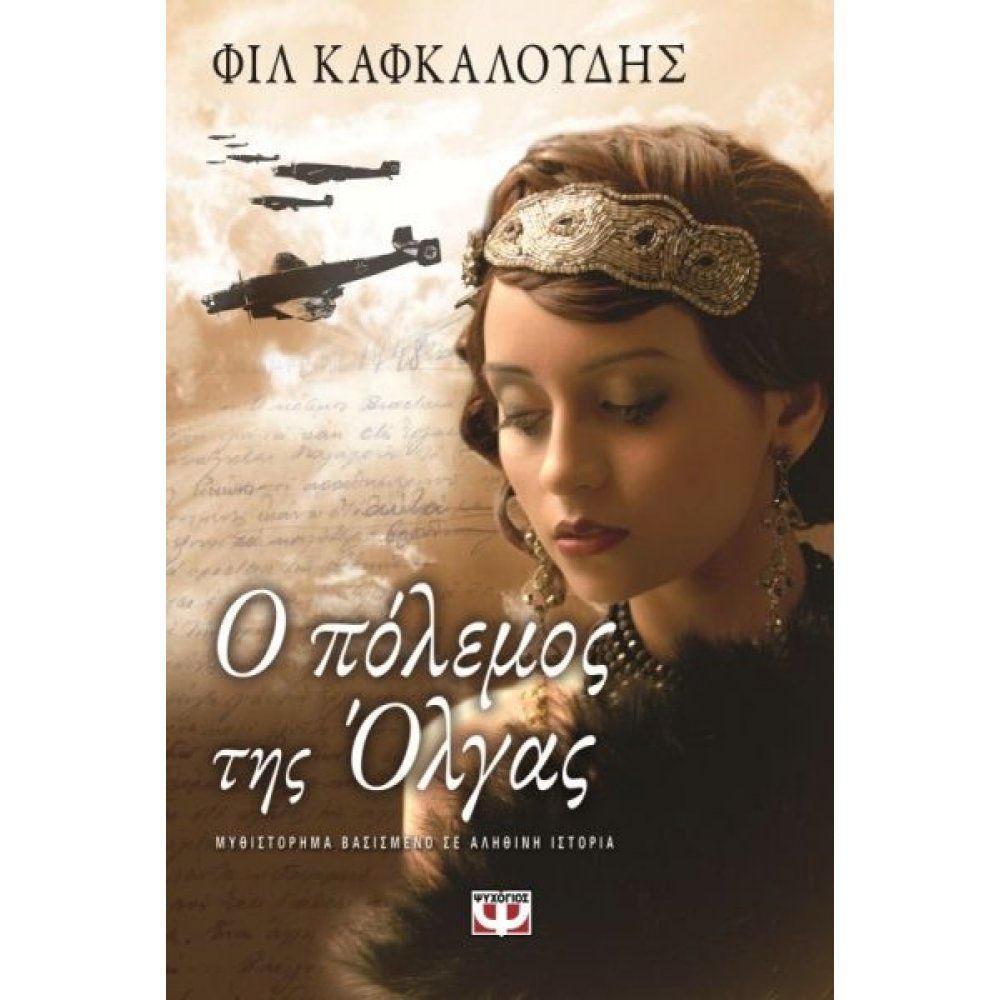

These narratives were made into a separate book, Olga’s War, by the Greek Australian author, Phil Kafcaloudes. A book that balances masterfully between reality and fiction.

Today, in a tribute to OXI Day, Mr Kafcaloudes shares with The Greek Herald his extraordinary story, a treasure from his family’s past.

Can you share the inspiration behind your book and what prompted you to delve into the story of your maternal grandmother’s role in WWII resistance efforts in Greece?

I had heard the story about my grandmother all my life. At Easters and Christmases, and aunties would tell the story about how she was a spy in Greece in World War II, and rescued service people from behind enemy lines and got them out to Cairo. It was funny though, hearing that story so many times I became almost desensitised to it over the years. It was really only in my mid-20s, when I told my fiancé about it, and she said how wonderful the story was that I realised what I had here. She encouraged me to write the story. And I took it from there, starting the research, which in itself was a long process that led to me deciding to fictionalise the story to fill the many gaps.

Your book touches on a lesser-known aspect of WWII history – the heroic actions of Greek resistance fighters. What message or insights do you hope readers will take away from your grandmother’s story and her contributions to the war effort?

The point I always make at book launches and writers festivals is that my grandmother never acted alone, for every brave deed she did, 10 Greeks or more risked themselves and their own families, and that is true bravery. I remember when I first went to Athens in 1988. I said to the proprietor of our hotel (hotel Phaedra in the Plaka) that my grandmother was a spy. He hardly looked up and said, ‘everybody’s grandmother was a spy’. That was a whack on the head to me and it made me realise that what my grandmother did was not a lone event. So many people did so many things in resisting the Germans, very few of them get any kind of accolade. Then again, very few of them would’ve wanted accolade for doing what they thought was necessary for their country and their people. I think stories like these need to be written because they die within two generations, just as my grandmother’s story nearly died.

With OXI Day in mind, how do you envision your book and your grandmother’s story contributing to the celebration of Greek heritage and the recognition of Greek Australian contributions during WWII?

Right now, I’m travelling around the Peloponnese where there are statues to the Greek heroes of the 1820s. These people are remembered for the unbelievable bravery and vitality they showed in the face of the Ottomans. This is what it is to be a Greek. There is a quote from President Roosevelt about bravery being defined as being a Greek. He was of course talking about how Greece repelled the Italians in 1940, in that most extraordinary defeat of the Second World War. Of course, Greece was overpowered by the Germans and their extraordinary fighting machine, but I think we need to remember how Greeks continued to resist the Germans, even if it meant massive retaliation. Australians did have a big role in the Allied forces, fighting against the German invasion and subsequently the occupation of Crete, but it must be remembered that New Zealand and Britain also never gave up on Greece.

I heard a story about how there was a village in Crete, where the Germans were about to shoot all the Greek men in retaliation for an attack on some German soldiers. The Australian and New Zealand sharpshooters were in the hills nearby with their highly accurate rifles. Before the German commander could issue the order to shoot the village men, the sharpshooters fired and killed every one of the German death squad. There was another story about how the same sharpshooters shot German paratroopers as they came into land, leading Hitler to order no more parachute drops in Greece. I think these are great examples of how an ordinary Australian or New Zealand could change a wall. But everything they did, they did with Greeks who were possibly not as well trained or equipped and probably also put the Australian and New Zealanders head of them when it came to food and supplies.

As a Greek Australian residing in Sydney, how do you personally connect with the significance of the National Day of Greece on October 28? Is it a special day for you, and if so, what makes it meaningful?

As a child, I never knew about OXI day. It was never taught in Australian schools, and certainly should be. We learned plenty about American history and British history, but this great moment involving a Prime Minister who was something of a tyrant, allowed him to show his Greekness. He must’ve known that the odds were strongly against him and that Italy was backed by an amazing German war fighting machine. He must’ve been tempted to allow Italy through Greece. But he said no. That was true bravery from a man who otherwise would probably not be too respected by history.

How has your research and storytelling journey reshaped your perception of the National Day of Greece and its importance?

As an academic, I always find myself subsumed by my research. But in the case of this story, it connects with me on many levels, the first of which is that it happened within my own family. It also showed that people, faulty as they are, can be their best in the hardest of times. I think the Oxi by Metaxas is a worthy moment to be defined as a national moment. I just hope that in my life I can show that sort of grace under fire.

Many Greek Australians take great pride in their heritage. How do you believe your book and your family’s history contribute to the preservation and celebration of Greek culture and history within the Greek Australian community?

Sadly, I think too much Greek history has been lost. This year I was a judge in a book prize for Greek authors in Australia. So many of the books were simply written by Greek offspring telling the story about how their parents came to Australia and struggled working in car manufacturing plants, and surviving by growing their own fruit in the backyard. Now these stories need to be told, but I wonder how many deeper stories are not told. I think millions of stories about the Greek Civil War, World War II, the depression, the First World War, the catastrophe in Turkey, have been lost or not written with a detail that is needed. I think too much of Greece with its fabulous history of oral storytelling has disappeared and cannot be revived. I wonder about the period between the great ancient Greek poets and playwrights and the modern era. How many of those stories survive? This seems to me to be a huge gap between modern and ancient Greece, and that is a terrible shame and a terrible loss.

Your transition from writing a novel to adapting it into a play is a unique journey. Could you share how this shift between mediums influenced the way you conveyed your grandmother’s story, and what was the audience’s reaction to the play?

The novel was published in 2011 in Australia and by Psichogios Publications in 2012 in Greek. At that time, I was hosting an international radio program on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. I did not have a lot of time to work on a sequel or an adaptation. But in 2017, when I started my PhD, I decided to adapt the novel into a play as part of that PhD, and to examine issues that had come up after the book’s publication. One of the big issues was the use of oral histories as a valid research tool. So as I wrote the play, I examined the research and writing process in my thesis and also questioned the facts that I had used, and the reasonableness of fictionalising the story, given the many holes in facts that I had. By the time the play was largely ready for workshop, I had learned much more about my grandmother, and so there was more accuracy in the story. But then again, being a play, there is much more scope for the words to be interpreted differently from how I envisaged. For once the play goes to a production team, the director has their own view on what they want the play to be, then the actors interpret the words in their own way, and the set designer can make it look completely differently from what I intended. But that is the journey for every playwright.

The play has not been staged publicly yet, but it has been workshopped using an award-winning director in Melbourne and three respected actors (including my own wife Jackie Rees, who is going to read scenes during my presentation at the Athens Centre). I recorded the workshop on video at a large studio, and the reactions were most gratifying. I am negotiating at the moment to have it staged in Melbourne, but I would love to put it on in Athens, the place where my grandmother was born, and where she worked for the resistance.

While I assume that most Greek Australians are familiar with your work, it would be great if you could provide some additional details about your Greek heritage.

Olga, the protagonist in the play, was born in Athens in 1902, but was given away as a baby to a woman in Alexandria in Egypt. She came to Australia with her husband, who was born on Kastellorizo and had come to Alexandria in 1921 to ask for her hand, even though she was 12 years younger. They married in Alexandria and went by boat to Australia, where he had what he claimed was a seafood restaurant (but was really just a fish and chip shop) and my mother was born in 1922 first of five children that Olga would have in succession. My dad (the man who brought me up, but not my genetic father) was born in Kastellorizo as well. My genetic father came to Australia in 1952 after having served as a boy in the resistance and seeking to get away from the Civil War. His family has a long Greek lineage. His own father (my genetic grandfather) had been jailed by the Mertaxas regime for being la eft-leaning journalist. Subsequently he was executed by the Germans as one of the Haidari 200. His great grandfather, I think, was the mayor of Corfu.

I was born in Sydney in 1960, and being a child of that generation, I did not go to Greek school and I embraced the whole groovy 1960s, when it wasn’t so cool to speak a European language, and it was certainly not cool to go to Greek school. It was only when I was in my mid-20s that I embraced my Greekness. My family had Anglicised its name from Kafcaloudes to Kaff. I was the only family member to revert back to Kafcaloudes. Although I did a research paper on my dad’s father, who was a builder in Darwin. He proudly built a building in the main street of Darwin in 1930 and labelled it The Kafcaloudes Building in huge concrete lettering across the front, which I think shows great pride in his name, even if his sons did Anglicise their names. Sadly, not much of the building is left and the building name has long ago disappeared.