By Professor Anastasios M. Tamis*

It is one hundred years since the destruction and uprooting of Asia Minor Hellenism from its ancestral homes. For thousands of years the Hellenism of the East, from the years of Homer and the pre-Socratic philosophers, from the time of Thales and Anaxagoras, from the sixth century BC, in dozens of cities of Ionia, Ephesus, Miletus, Klazomenae, Halicarnassus, Colophon and Phocaea (to refer to some of them), numerous poets and historians, mathematicians and geographers developed and cultivated philosophy, poetry, theogony and the sciences. It was later, during the Roman conquest, that the East was first referred as “Asia” and Hellenism as Asia Minor Hellenism (until then the place names took the tribal name of the people who inhabited a particular region).

Later, it was Hellenism that essentially accepted, developed Christianity, and transmitted it to the rest of the world. Apostle Paul relied on this Hellenism of the East for the spread of the new religion, as this is attested by his dozens of letters to the inhabitants of these cities. In this region of our East (Anatolia), over and above the unbridled fanaticism, finally and despite the crimes against the Greek culture and the followers of the Greek Religion, the Hellene was reconciled with Christ.

In Anatolia, the ancient Greek civilization was comprehended and accepted by the fathers of the Christian Church, especially by those who studied and highlighted the importance of Greek culture. Basil the Great explicitly mentions in his writings that it is impossible to understand Christianity if one has not studied the concepts of ancient Greek civilization. In the Hellenic Anatolia appeared the first frescoes of the Christian churches, which had among the Saints of Christianity, in halos and Plato and Aristotle and other poets and philosophers of Greek Antiquity, as their saints.

There in Caesarea and Cappadocia hundreds of Greek villages emerged and for hundreds of years maintained their Greekness and their Christian Faith. In the cities and towns of Asia Minor, the Greeks there set up their schools and girls’ schools, they built ecclesiastical schools in the Greek language, temples and schools of the Nation, they erected monasteries of culture and learning, they occupied positions of prestige and influence, they emerged as teachers of the Greek Nation, hierarchs, frontrunners and martyrs of the Nation.

Many who got rich as merchants and industrialists, benefited their towns and villages, built beautiful temples and schools, built orphanages and geriatric hospitals, cultivated the Greek letters, published newspapers and books, recorded, and maintained the ancient Greek literature. In Ionia, Cappadocia, the East, Anatolia Asia Minor (whatever we want to call them), flourished and operated for hundreds of years a Hellenism, essentially more cosmopolitan, more influential, more robust than the rest of the Hellenism of Western Greece, beyond the Aegean.

Smyrna, at the end of the 19th century, was the Paris of the East, the small Athens of Greek antiquity. Wide open boulevards, well-structured roads, rich districts that ascended the hills that erotically enclosed the city, wonderful buildings, obvious wealth and nobility, rich neighborhoods of Greeks, Armenians, and Jews. A bride of the Eastern Aegean, who had opposite her the other bride of the western Aegean, Thessaloniki. Similar cities in geographical gifts, in nobility, in taste, in cosmopolitan character.

With the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, hundreds of thousands of Christians, in their overwhelming majority, Greeks, and Muslim Turks were compelled to leave the villages and towns where they lived, to expatriate, in order to define the borders of a modern post-Ottoman Turkey. It was the largest population exchange that had taken place until then in the history of the peoples of the planet.

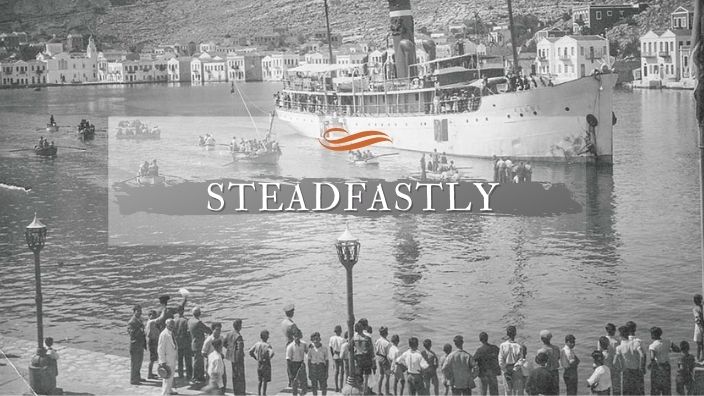

More than a million Greeks were forced to evacuate the villages where they had buried their parents and ancestors, the neighborhoods, and their homes, where their grandparents had grown up. Hundreds of thousands of Greeks took in their few suitcases and makeshift parcels, everything they could carry, there they placed the icons of the Saints of their faith; there they placed some photographs of their own; hid there the few valuables they had; they worshipped for the last time the ancestral tombs, they lit the last candle to the Holy Protector of the area and they were led with arabades, and on foot to the nearby ports of Asia Minor, as refugees in Greece.

And in November 1919, the Greek army appeared there in the port of this “Greek-occupied” city of Smyrna, over 80,000 initially, then numerically larger. The Battalions of the Evzones and the Cavalry, the Army of the Archipelagos, Macedonia and the Cretans landed. Paraded through the streets of Smyrna and the Greeks poured out with the Greek flags, with songs and tears of unspeakable joy to welcome them as liberators and brothers. Similar feelings were felt by the rest of Hellenism in Lycaonia, Cappadocia, Lycia, on Pergamos and Proussa, up to the shores of the Bosporus. The Turks were numb, humiliated, rightly restless, despite the reassuring encouragements of the Greek officers. The Greek Army in the first almost two years made sure to consolidate its presence only in areas where the Greek element was demographically abundant. It proceeded internally towards the Aidinio and then to the north up to Proussa, in order to protect Pergamos, Kydonies and Smyrna.

Initially the goal was not the dismemberment and conquest of Turkey. Venizelos and Metaxas insisted that the Greek Army should not be removed from the sea and the supply centers, especially Smyrna, to stay only in areas where a solid Hellenism lived, not to expand into the interior of Turkey, the Far Anatolia, so as not to find themselves among foreign populations without support and supplies. From July 1921, with the synod in Kioutachia, the Greek officers did exactly the opposite. They undertook expansionist action to defeat the Turks, to exterminate them, to occupy Ankara, which was the main supply center of Kemal Pasha and to end their conquest struggle (in the next article we will refer to the painful points there that were the causes of the Disaster).

This is the period when the facts had changed. From July 1921, when the famous Campaign of Ankara or Sagarios began (as it was called) aiming at the capture of Ankara by Greek troops until September 1921, the Greek Army defeated the Turkish soldiers and irregular Tsetes along the entire length of Ionia.

They defeated them at Aidini, also outside Proussa, further south and east. The Turkish troops were constantly retreating in defeat, were regrouping, and attacking again. They used to lose the battle and after days they used to re-appear with new attacks. The Greek Army passed through the Salty Desert victoriously, passed through Sagarios and the terrible hills of Cale Groto, defeating the constantly retreating Turks, until they reached 80 kilometers from Ankara. There the Greek Generals realized that despite their victories, they had found themselves with huge losses and desertions, far away from the supply centers and could no longer even advance, but also worse, that they could not win this War.

Thus, from September 1921 until August 1922, the Greek Army remained inactive, without any strategy, without any attack. On the other hand, Kemal, having the support of the Russians, but also of the French and Italians and knowing that he had won the war, did not attack. He let the apple ripen and rot on the tree to fall on his own. And when every diplomatic effort by Greece and England to reach a diplomatic agreement, Kemal rightly refused, unless the Greek Army first abandoned Asia Minor, he began in August 1922 his attack against the Greek Army.

This resulted in the disorderly retreat of the Greeks and the destruction of Asia Minor Hellenism.

Next week we will describe the causes of the disaster and the week after next we will refer to the consequences of this disaster for Greece and the Hellenes.

*Professor Anastasios M. Tamis taught at Universities in Australia and abroad, was the creator and founding director of the Dardalis Archives of the Hellenic Diaspora and is currently the President of the Australian Institute of Macedonian Studies (AIMS).

READ MORE: Agreements must be respected: ‘pacta sunt servanda’