Australian tales of heroism and sacrifice by the ANZAC’s in Greece during the second World War unites continues to unite the two countries. To this day, new stories continue to emerge of the battle scars endured during one of Allies’ worst defeats in the war.

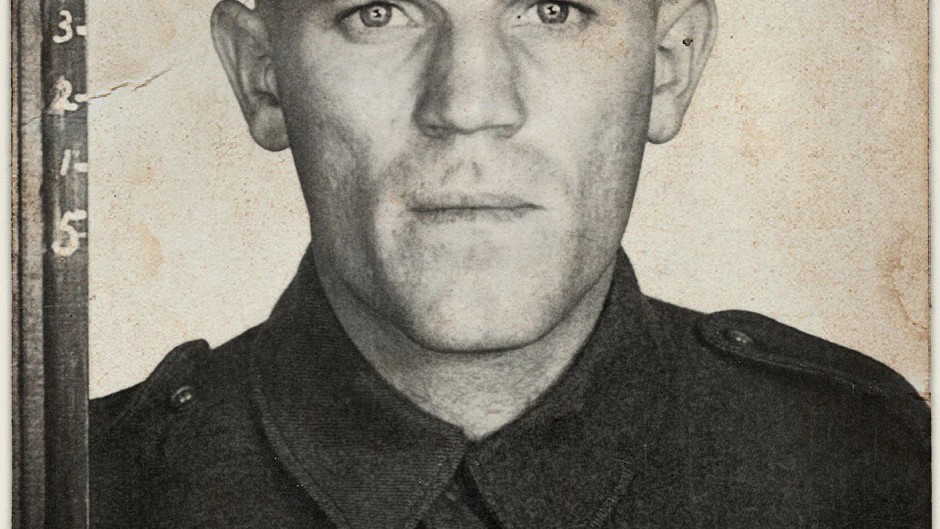

ABC News have published the story of John Robin Greaves; An Anzac trooper who beat the odds to survive a Prison of War camp in Greece.

Born in Shanghai in 1914, Greaves, known as ‘Jack’, was the eldest son of a mixed-race family which had made its home in the foreign-controlled Chinese treaty port two generations before.

Escaping Shanghai after defending in the Japanese incursion, Jack sailed to Sydney and enlisted at the recruitment office at Sydney’s Victoria Barracks.

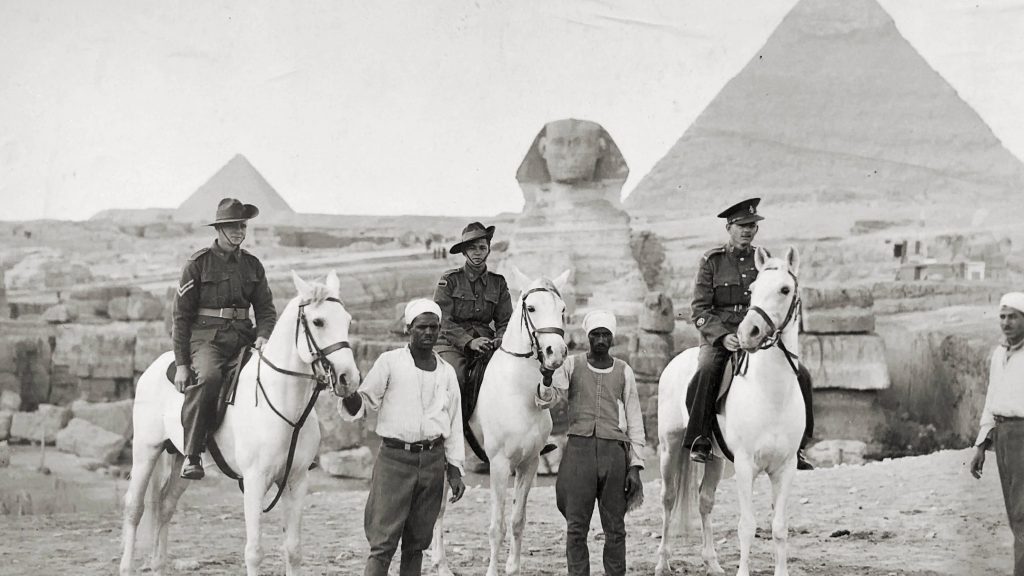

After travelling to Palestine, then eventually Cairo, Jack spent a few days camped near Athens before being dispatched north to Veria Pass, high in the mountains of northern Greece. By early April, the German invasion was underway and the entire Allied expeditionary force was soon in full retreat.

Pinios Gorge, also known more poetically as the Vale of Tempe, lies near Greece’s eastern coast. Defending the heartland from invasion, Greek, Australian and New Zealand troops attempted to prevent the Axis advance on April 17, 1941.

Private Greaves was there as part of what the diggers called the PBI — the Poor Bloody Infantry. His mortar platoon was among those ordered to help slow the German advance, which threatened to cut off the main Allied retreat.

The Anzacs proved to be no match for a combined tank and infantry assault supported by the Luftwaffe’s overwhelming air superiority. The battle extended into the following evening, and at dusk the German Panzers broke through, scattering the defenders.

“Orders were then given to us to retire, every man for himself. After spiking the mortars with grenades down the barrels … we made for battalion HQ,” Jack wrote in a report. “Close behind, a German tank seemed to be aiming its fire directly at me. Flaming onions [tracer rounds] flew past as I ran for my life.”

He hopped into a truck heading south. But in the twilight, the Germans had cut off their escape route. The truck had only travelled a kilometre when a single shot rang out.

“Then all of a sudden hell broke loose … The Jerries [Germans] were in a perfect ambush … Machine guns, mortars and Very lights [flares] turned night into day for a few brief moments,” Jack wrote in his account of that evening. “Before I realised what had happened, Jerry was searching us for arms.”

He was now a prisoner of the Reich. “I felt in a daze,” Jack recalled, “and I am sure my mates did too.” Nine days later, the Germans swept into Athens and following that, the rest of the Greek mainland was overrun.

Although the Germans were victorious, they were delayed just long enough to allow thousands more retreating Allied troops to avoid capture.

As enemy forces streamed south, Jack was marched north to Dulag 183, a notorious prisoner of war (POW) transit camp in the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki, or Salonika as it was then known.

In a letter to his sister Beatrice, Jack described camp life as being a “hellish … nasty nightmare” where poor sanitation, meagre rations and backbreaking work became the norm. The POWs were attacked by what he described as “all species of body vermin ″ which covered their bodies and the rags that passed for bedding. “Life there was an unbelievable hell,” he wrote.

On June 25, he was among about 2,000 prisoners assembled on the camp parade ground and given rations meant to last the four-day rail journey to more permanent camps in Germany and Austria. As they marched to the station behind a German brass band playing Roll Out the Barrel, Jack knew that the train journey was his best and last chance to escape.

Jack paired up with Private Tom Walker, a fellow digger from his battalion, and they made their way to the back of a carriage near the ventilation hole. At 7:00pm, the train pulled out of the station.

The night wore on and the train crossed the border into German-occupied Yugoslavia. Jack made his move, squeezing through the tiny window and onto the buffers and waited until the train slowed down going uphill. “And luckily, we didn’t jump into anything because it was still dark,” Jack later recounted.

The train stopped briefly and the guards fired a few parting shots into the bushes before resuming the journey without the two escapees. “Kaput! Kaput!” he heard them shout, as if to indicate that the bullets had hit their mark.

Jack and Tom spent the next six weeks navigating their way south from Yugoslavia back into Greece, following the path of the Vardar River valley before heading east towards the coast.

To read the rest of Jack’s story, click the link to ABC News’ profile: https://ab.co/36qTL0X