By Despina Karpathiou

You might think that when we talk about loneliness, we’re referring to someone living on a remote farmstead—someone who only goes into town once a fortnight and catches up with everyone then spending most of their time alone.

But no, we’re talking about city dwellers—people who live among millions of others. Ironically, these are often the people who feel the loneliest.

At this point, the average person might be scratching their head. Why, in a society where people are more connected than ever, do so many still feel alone, misunderstood, or cut off from meaningful relationships? This happens despite the rapid growth of social media, video calls, and online communities.

Loneliness remains one of the most common, yet frequently overlooked, emotional struggles among adults—especially young adults.

Loneliness has been linked to premature death, poor physical and mental health, greater psychological distress and general dissatisfaction with life.

Loneliness among Australians was already a concerning issue before the COVID-19 pandemic, to the extent that in 2022 it has been described as one of the most pressing public health priorities in Australia.

But what exactly is loneliness? And why does it continue to grow in a society with so many opportunities to connect?

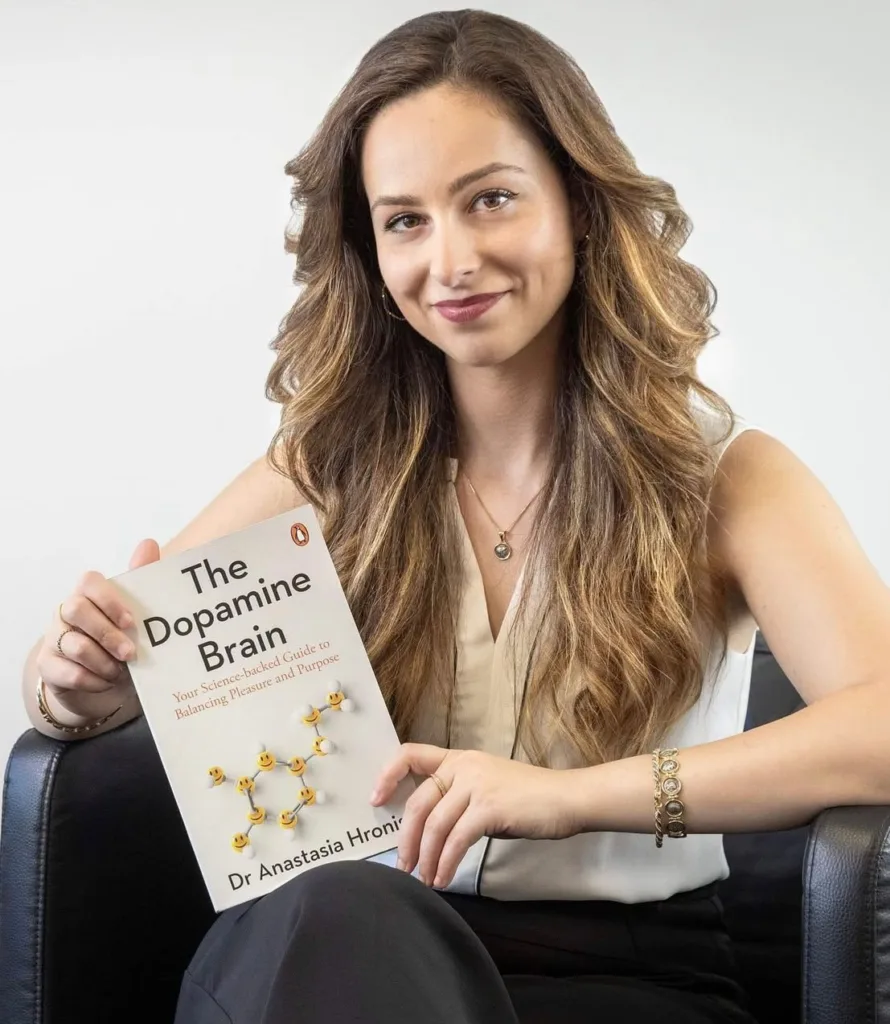

The Greek Herald spoke to Dr Anastasia Hronis, Clinical psychologist, academic & author of The Dopamine Brain about this modern-day epidemic plaguing our young adults.

Define loneliness:

Dr Hronis describes it as a feeling of wanting more social connection or better relationships than what we currently have.

“Loneliness is different from being alone. We can spend time alone and not feel lonely. On the flip side, we can be surrounded by people and yet still feel lonely and isolated,” she explains.

Loneliness refers not only to the number of connections we have, but also to the quality of our relationships with others.

“It’s important to remember that everyone’s desire for social connection is different… It’s not necessarily about how many friends we have, but rather how we feel when we’re with them. It’s a natural human desire to want to feel seen, heard, and understood by others,” Dr Hronis says.

In a world where everyone is so connected digitally, you’d think it would be easier for people to combat loneliness. So, why does it seem to be the opposite?

Dr Hronis explains that digital connections can feel less fulfilling for some people.

However, for others, the online world provides access to communities they wouldn’t have had the opportunity to connect with in real life.

“Think about, for example, a young LGBTQI+ person living in a rural part of Australia. The online world can open opportunities for them to form meaningful connections in communities they might have limited access to in real life,” she says.

The new digital generation has helped many connect, but not in the way most human beings need.

So, why is it so difficult to admit that you’re feeling lonely?

Dr Hronis says this is because admitting loneliness requires vulnerability, which means opening up and putting your feelings on the line.

“It takes vulnerability to acknowledge that we feel lonely. This is a hard thing to do,” she explains.

Another factor is the Western world’s motto of “I don’t need anyone” and “I can do it myself,” which has resulted in a culture that praises extreme self-reliance and hyper-independence, while real, in-person communities have become less common.

Dr Hronis explains that this isn’t helping the loneliness epidemic.

“In its extreme form, it can create a worldview where asking for help and receiving help is deemed ‘weak.’ We know that this simply isn’t true!” she says.

When asked if she thinks social media is to blame for many mental health issues among youth, Dr Hronis explains that it has contributed, but ‘not entirely.’

“I think in some ways social media may have contributed, but there are many other factors to consider about how societies work nowadays including academic and career pressures, economic uncertainty, rising cost of living, climate anxiety, global issues, etc.,” she says.

Combatting the loneliness epidemic will require addressing how societies function. Dr Hronis says that we cannot blame one issue.

“Rather, we need to think about how we can increase quality connections with other people in society, form meaningful communities, and be inclusive and open to all,” she adds.

Always remember to reach out, especially to those who are quiet, and ask if they’re okay. A conversation could change someone’s day or save a life. Learn more here.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with your mental health, please contact Lifeline Australia on 13 11 14 or visit www.lifeline.org.au / Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636 or visit www.beyondblue.org.au