By Peter Kirkpatrick.

A really good restaurant deals in more than food. It feeds the spirit too. Quality dining is not a simple matter of rich surroundings, crisp white linen or silver service. It’s often not even the food itself. The recipe is based on that set of mysterious human ingredients collectively titled atmosphere. Depending on what atmosphere you’re looking for, it’s possible to dine sumptuously in the most ordinary surroundings — as anyone who ever ate at the old Garibaldi’s in East Sydney during its heyday can testify.

Liberation from the domestic tyranny of meat-and-three-veg has led many people to overlook the culinary variety of Australia in the past. In 1963, the poet Kenneth Slessor pointed out that both French and Chinese restaurants “flourished superbly” in Sydney before the Second World War. His Bohemian colleagues on the fringes of literature and journalism might have added that Greek food was also well-represented in at least one place: Andrew’s Continental Cafe, two floors up on the corner of Park and Castlereagh Streets. For writer Dulcie Deamer, Sydney’s Queen of Bohemia, “See you at the Greeks’” meant only one thing: “No other Greek cafe existed for those in the know.”

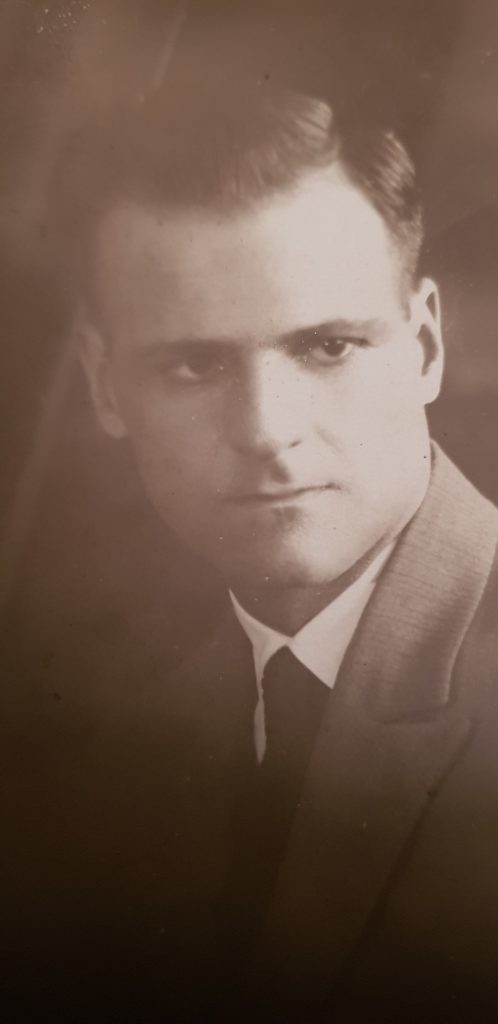

It had been founded in 1925 by Andrew Arestides, a Cypriot who went on to become a major figure in the local Greek community. For his philanthropy and many good works for fellow migrants he has in fact been described as “the father of Cypriots in Australia”. Arestides arrived here as a lone adolescent around 1917 and helped establish a restaurant called the Panellenion Club. The Continental Cafe was entirely his own venture, and consisted of an outer club room, where men played backgammon and drank coffee, separated by swing doors from the dining room itself — as “unadorned as a plucked fowl,” according to Deamer. Despite its plain decor, the Cafe was a home away from home to many Greek Cypriot men who had no family in Australia. A corner of the club room was sublet to a Greek barber.

It’s not hard to guess the attraction of the Continental Cafe for the artistic set. Like its Greek regulars, to some extent, they also felt a sense of being on the margins in an aggressively conformist society — as Australia was in those days. The Cafe’s upstairs location gave it the ambience, not only of a club, but of a place of refuge, a hideaway. Adding to the mood of multicultural tolerance was a cockatoo that could swear in several languages.

Writers and artists had been going there for coffee for some years before Friday nights became special occasions sometime in the early 1940s. A group of Bohemians who took the Italianate name of the I Felici, Letterati, Conoscenti e Lunatici – the Happy, Literary, Wise and Mad – had adopted the Cafe as its regular Saturday lunchtime venue in the late 1930s. When I Felici started to break up, Arestides himself suggested to its remaining members that Friday nights might be a good time to rekindle the Bohemian flame, as it was already proving popular with what Dulcie Deamer called “our type” of people.

The restaurant’s menu consisted of such things as Greek roast lamb, cabbage rolls and – a little incongruously – spaghetti (a Bohemian mainstay). Post-prandial activities on Friday nights added a special piquancy to it all. In Deamer’s words: “Tables are pushed back, and to dance tunes broadcast from a device Andrew has installed enthusiasts from twenty to seventy waltz, jog and shuffle; also invent fancy figures and do solo turns. Some of us dance with the Greek waiters, for we are all one family. As it gets later, and there are more dead marines… hilarity increases, and some try high kicking, push-ups and other physical feats.”

Besides the more predictable ragbag of poets, journalists and cartoonists were such refugees from respectability as “a sentimental butcher who constantly sang sentimental ditties,” and a grandmotherly woman who performed hornpipes. Deamer herself would recreate her old party trick of doing the splits on a table-top, and be shouted an ouzo by the proprietor. On the night of the Annual Artists’ Ball at the old Trocadero in George Street the Cafe would be filled with fancy-dress figures, much to the amusement of the card-playing Greeks in the club room.

Chips Rafferty was a regular too, reciting such ballads as “Three Jolly Good Bastards Are We”. The Cafe actually launched his acting career, for it was while delivering beer and wine there that Rafferty was introduced by Arestides to a casting director at Cinesound. According to Rafferty’s biographer, Bob Larkins, “they were looking for a tall thin bloke to play a runner in a new comedy film”. After a couple of bit parts, Rafferty was given a starring role in Charles Chauvel’s epic Forty Thousand Horsemen, and went on to become a legend. He later tried to interest Arestides in forming a film production company, but Andrew had the business sense to see that there was little to be made from an already depleted post-War Australian film industry.

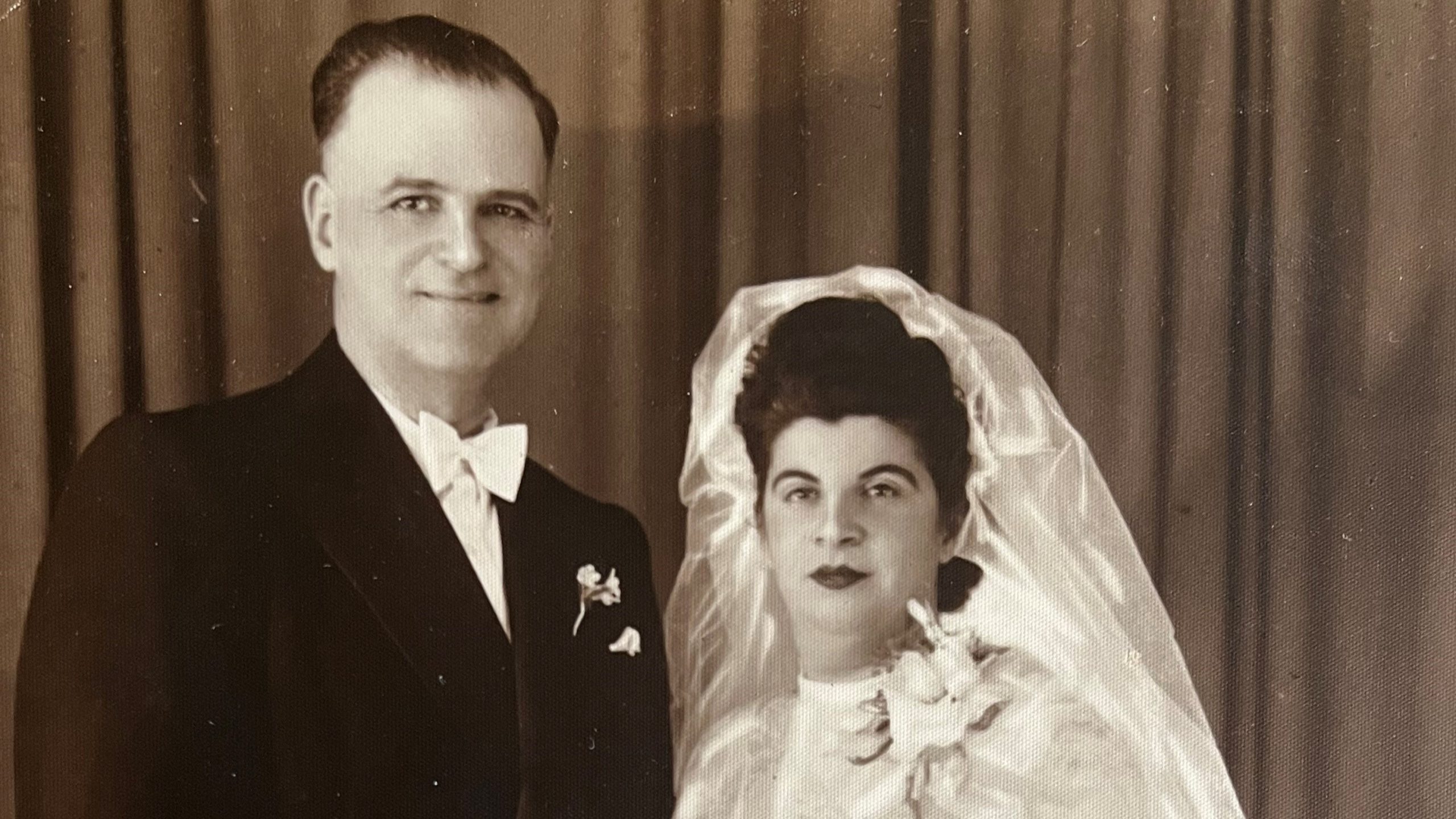

As the Cafe prospered, Andrew was able to bring his mother and four sisters out to Australia. Cypriot custom meant that he had to see his sisters married before he could take a wife. In 1946, Andrew married Anna Hadjiantoniou, a childhood friend of one of his sisters. They became engaged by mail, and met each other for the first time when Anna arrived from Cyprus a month before the ceremony. It was a very happy union, producing four children whose marked artistic interests perhaps owe something to the subtle influence of the Cafe.

When Andrew Arestides suddenly and prematurely died in November 1958 it was not only the local Greek community who mourned. “Our Andrew, that towering pillar of Bohemia,” wrote Dulcie Deamer, speaking for all his Bohemian friends, “whom very many will remember with respect and love, was… as wise and firm as he was warm-hearted, and he was to exhibit a constancy towards us rare in human relations.” For her it was the end of an era — one that had stretched back to what she called the “Golden Decade” of the Roaring Twenties. Andrew’s wife Anna maintained the restaurant until 1964, but things were never the same.

Crime fiction writer Marele Day has described Sydney as “a town that has every cuisine in the world available to it”. It wasn’t always like that. What variety there once was in “ethnic eating” should be remembered, however, lest we misrepresent the past and the place that other cultures have always had within it. Andrew’s Continental Cafe was a very lively part of that past, highlighting a cultural dialogue about which little has been written, but which has nonetheless contributed to that great banquet of life which is Sydney itself.