By Vasilis Vasilas

After the 1890s, Sydney’s small Greek community’s spikes in its population were subsequent to Greece’s national crises- losses in the Greek Turkish Wars of 1987 and 1919- 22 respectively and global crises- World War I and the Great Depression. Additionally, many pioneering Greek migrants who initially worked in Australia’s rural areas gravitated to urban centres such as Sydney.

Although this is an early stage of the Greek community’s development, the increasing numbers of Greeks settling in Sydney is reflected in the need to satisfy social and spiritual needs, and in the organisation of the community itself. Hence the establishment of the Greek Orthodox Community of New South Wales (1898), quickly followed by the construction, in Surry Hills, of the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church are indications of how the growing number of Sydney’s Greeks prompted the community’s further development.

With the Exchange of Populations between Greece and Turkey in 1923 and the enormous pressure 1, 600, 000 refugees (from Asia Minor) placed on Greece’s small, vulnerable economy, migration abroad was seen as a hopeful opportunity for job prospects for thousands of Greeks and Australia was one regarded as an alternative destination.

What transpired within the Greek community was its members balance of maintaining their connection to their homeland, Greece, and their adopted homeland, Australia. These migrants may have settled on the other side of the world but their connections to Greece were strongly maintained.

In the 1920s, the definite ‘spikes’ of Greek settlement in Sydney did not go unnoticed by the Australian authorities. By the mid-1920s, there were pressures to relax the Australian Federal Government strict quotas- the capping of annual Greek arrival numbers- to Australia by, “Senator G.F. Pearce, the Minister for Home and Territories, promised to place before Mr S. M. Bruce, the request of a Greek deputation which yesterday asked for the removal of the new restriction against Greek immigrants limiting their admissions to 100 monthly… the Greeks in Australia felt that discrimination by the Federal authorities between Greek immigrants and those of other European countries was unjustified.” (“Sydney Day by Day”, ARGUS, February 26, 1927).

With these growing numbers, there was an evitable need for the Greek community to further organise itself, “To an observer’s eye, Sydney’s Greek presence was noticeable, “The Greeks are becoming strong enough numerically to be noticeable as a well-defined section of the community. They operate in various avenues of trade and also in professions. They are building a large cathedral. There will be two Greek Church buildings owing to internal differences of opinion, but they will simply supply two arguments in support of the claim that the Greeks are not entirely immersed in material pursuits. Now we are to have a Greek ball- not one merely dressed in remote Athenian styles, but one promoted entirely by Greeks and designed to earn money for the Children’s Hospital and Limbless Soldiers Association. His Excellency Sir Dudley de Chair has promised his patronage.” (Barrier Miner, Saturday 31 January 1925)

Other socio- cultural groups were established during this time; the growing numbers of Greek migrants from the same area in Greece inspired these members to establish associations in Sydney based on their ancestral areas such as Kythira, Castellorizo, Ithaka and Lesvos. Moreover, AHEPA AHEPA (Australian Hellenic Education Progressive Association) was established to promote and support Greek issues in these migrants’ adopted homeland.

Another manner Sydney’s Greek community maintained its connection to Greece was the need to import items to aid this maintenance. Importing items from Greece for the growing Greek community subsequently inspired individuals’ entrepreneurial vision to establish shops or warehouses to store and sell these items. These movements should not be underestimated from a historical perspective because it is during this time these Greek products enter the Australian market, via the Greek community. With the establishment of so many Greek shops and warehouses, what emerges is Australia’s first Greek business network emerges. What is also interesting about these developments is the locality of so many Greek businesses in close proximity of each other in Sydney city and what could be regarded as “the Greek quarters”.

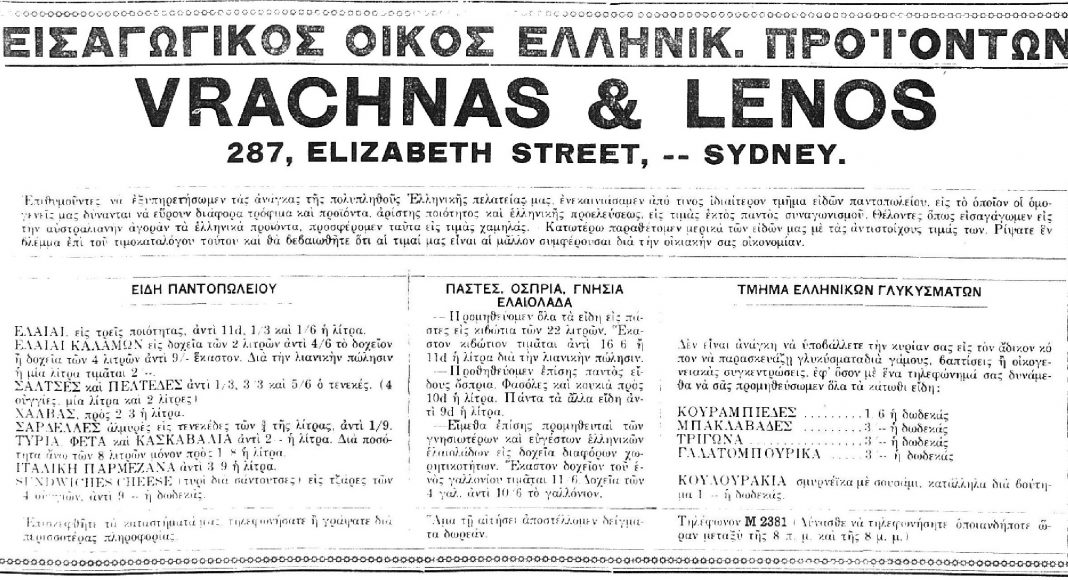

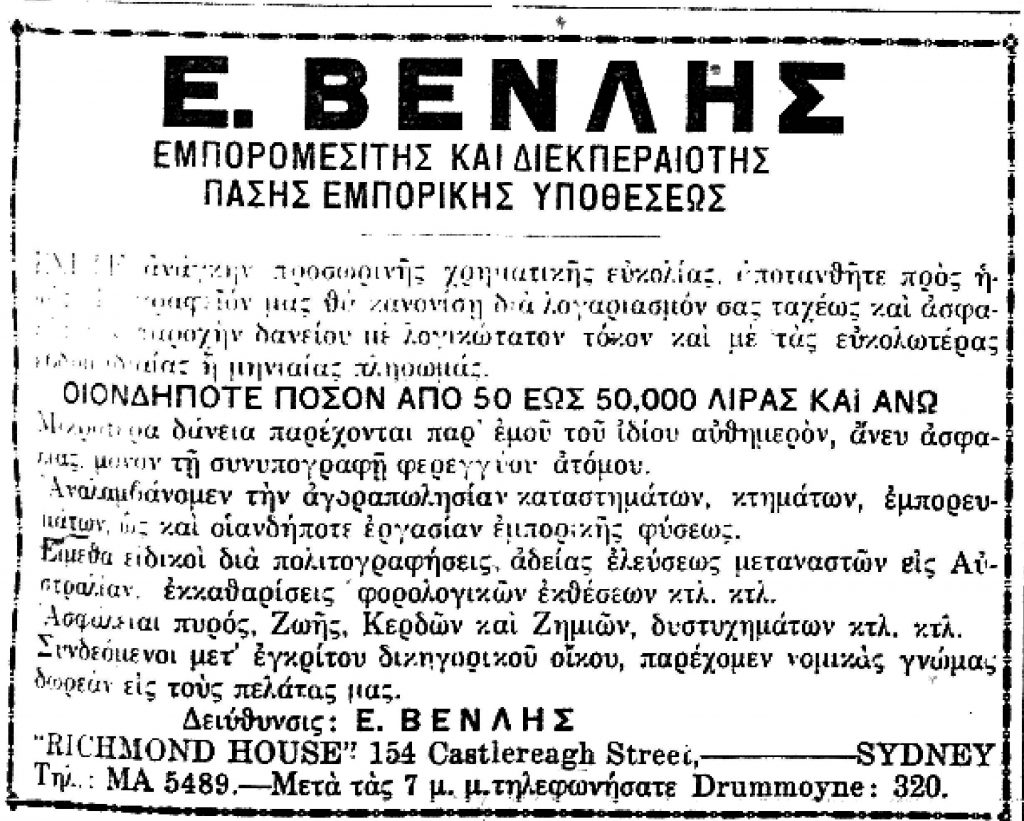

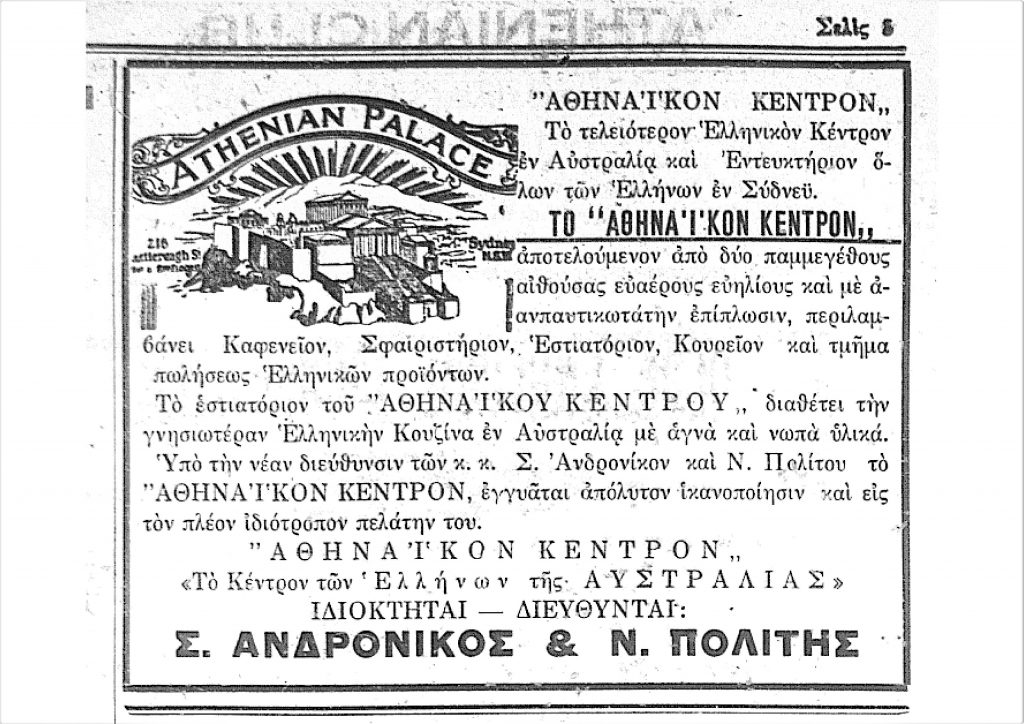

Examining The Pan Hellenic Herald’s (“ΠΑΝΕΛΛΗΝΙΟΣ ΚΗΡΥΞ”) edition in the late 1920s reinforces the emergence of Sydney’s Greek market for imported Greek products, the vibrant activity of the Greek business network and open identification of Greek businesses as being Greek.

By the late 1920s, (Sydney’s pre World War II) Greek migrants had already established a diverse range of shops and businesses. There were (already) shops with Greek names, such as the club “ Pantheon” on Castlereagh Street and Theodoros Crithary’s “Embros Trading Company” on Sussex Street. Although the local Greek newspaper, “ΠΑΝΕΛΛΗΝΙΟΣ ΚΗΡΥΞ” , was based in Castlereagh Street, it should be noted that its owner, Alex Grivas, also imported Greek newspapers, magazines, and books, from the USA and Greece. The “Andronicos Bros Fruit Exchange” on Bathurst Street was the exclusive representatives for importing products, such as pasta, from the iconic Greek company Misko. Greek cognac and ouzo were sold at the Barlington Hotel. A network of importers catered for Greek migrants’ need of products from their homeland. There were importers of olive oil from Greece such as George Skarlis Olive Oils in Castlereagh Street and S. Souris in Crown Street. Vrachnas and Lenos general store (παντοπωλείο or general store) on Elizabeth Street sold everything from Greek sweets (baklava and galaktobouriko), biscuits (shortbread, koulouria) olive oils, cheese, legumes and sardines; their advertisement states that they were catering for their ‘many Greek customers’.mWith so many Greeks in businesses, E. Venlis had established a business agency in Richmond House on Castlereagh Street12 while M. Lazarus and Co. Were on Bathurst Street.

Interestingly, Sydney’s growing demographics provided opportunities for businesses of a social alternative; these establishments combined several businesses into one, offering a Greek cuisine, barber, games room and a section selling Greek goods. S. Andronikos and N. Politis ran the Athenian Palace, while Michalis Loukas, Nikolaos Koufos and Michalis Tsakaris ran the Hellas‘ kafeneion’ on Park Street. Greek in name and appearance and offering a Greek cuisine and selling Greek goods, this is the early stage of the Greek identity developing in the Sydney marketplace as such businesses are catering for the demand coming from the city’s growing Greek demographics.

Examining this snapshot of Sydney city’s Greek businesses of 1928-30, through the advertisements placed in the local Greek-Australian newspaper, captures the growing vibrancy and strength of the Greek presence in the city; if we were to include all Greek-run cafes and milk bars in the area, the city’s Greek business network is one of significant stature.

What this highlights is an emerging market for Greek products to cater to the Greek migrants’ demands. Whether it was for imported Greek cheeses, olive oil, ouzo, or Greek sweets and cakes, or Greek newspapers and books, Greeks took this opportunity to establish the shops, and warehouses needed to meet these demands.

Hence, the diversification of Greek businesses and the importation of Greek products was firmly established before the post-WW II influx of Greek migrants. With the mass migration that was to follow, however, the higher numbers of Greek migrants settling in Sydney would increase the demand for Greek products and services to a much greater scale.

Vasilis Vasilas has compiled and published several books within Australia’s Greek, Estonian, Ukrainian and Jewish communities. His most recent publication, “Little Athens (Volume One): Marrickville (Part One) looks at the diversification of Greek businesses and contribution to the local, national and international markets.